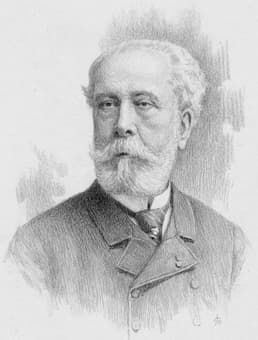

Paraire: Édouard Lalo (1891)

The 1870s were a time for Spanish, or Spanish-themed music, especially by French composers. Édouard Lalo’s Symphony espagnole was written in 1874 and a months after its February premiere, Bizet’s Carmen has its premiere at the Opera-Comique in Paris. Pablo de Sarasate’s Zigeunerweisen (Gypsy Airs) had its debut in 1878 in Leipzig, and roving bands of Spanish student plucked string ensembles roamed the streets of Paris during the 1878 International Exposition, bringing more than a hint of exoticism to the sounds in the air. Emmanuel Chabrier’s España came following his 1883 trip to the country.

Pablo de Sarasate (1905)

Édouard Lalo (1823-1892) had a family with Spanish roots, but which had been in France since the 16th century. His father disapproved of his musical study and his first years in Paris were difficult, with his music finding little success. He joined a string quartet as a violinist and then founded his own quartet. In the 1870s, however, first with his Violin Concerto (1874) and then his Symphonie espagnole (also 1874), he rose as a composer. The two works had been written for the Spanish virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate and signalled the start of his fame.

Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole immediately belies its title by actually being a violin concerto. After the brisk low-string and percussion opening, the violin enters, and we are no longer in the world of the symphony. One commentator actually called the work a mix of the symphony, the concerto, and the German Romanze – there’s lots of Spanish (or Spanish-type) ideas, beginning with the opening flamenco gesture in the violin. The alternating two-three rhythms will give the life to the work, as does the contrastingly lighter second theme.

Édouard Lalo: Symphonie espagnole, Op. 21 – I. Allegro non troppo (Christian Tetzlaff, violin; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra; Libor Pešek, cond.)

The second movement takes us to an outdoor fiesta – you can imagine the violinist as the lead dancer and the rest of the orchestra as the other dancers or the onlookers to the action. Increasing demands are made on the skill of the violinist and the movement becomes the player’s turn to take the centre of attention.

Édouard Lalo: Symphonie espagnole, Op. 21 – II. Scherzando: Allegro molto (Jascha Heifetz, violin; RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra; William Steinberg, cond.)

The third movement is much more dramatic and brings a pseudo-tango melody that has a curious heaviness. This movement was commonly omitted in the early 20th century – dropping this movement made a more realistic four-movement symphony form (we’ll ignore the common three-movement concert form!) – largely because the recording technologies of the early 20th century made it difficult to get all the movements on to regular recordings. Also, the idiosyncratic orchestral writing made it difficult to translate to a piano accompaniment.

Édouard Lalo: Symphonie espagnole, Op. 21 – III. Intermezzo: Allegretto non troppo (Tianwa Yang, violin; Barcelona Symphony and Catalonia National Orchestra; Darrell Ang, cond.)

The fourth movement Andante is melancholic and lyrical, again bringing in Spanish themes to the violin line.

Édouard Lalo: Symphonie espagnole, Op. 21 – IV. Andante (Mischa Elman, violin; Vienna State Opera Orchestra; Vladimir Golschmann, cond.)

The work closes with a bravura Rondo full of elegance and charm. It’s one of the most recognizable movements from the work. As the final movement, it provides so many opportunities for virtuosic display.

Édouard Lalo: Symphonie espagnole, Op. 21 – V. Rondo: Allegro (Isaac Stern, violin; Philadelphia Orchestra; Eugene Ormandy, cond.)

With the Violin Concerto and the Symphonie espagnole, Lalo’s career was assured. Since both works were in the hands of the leading violin virtuoso of the late 19th century, Pablo de Sarasate, they remained in the concert repertoire for decades. It’s not known why Lalo created this 5-movement violin concerto and called it a symphony. It may be that he had too many ideas to confine it to the regular violin concerto structure. Even today, more than 140 years later, the Symphonie Espagnole continues to be recorded and performed.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter