© The Korea Times

This is a never-ending question that always sparks heated debate, which sometimes even the jury can’t come to an agreement. It was also why Fou Ts’ong protested against awarding the first prize to Stanislav Bunin by not signing the verdict in 1985.

To answer this question, one has to bear in mind why Chopin Competition was organised in the first place. It was founded by the Polish piano professor, Jerzy Żurawlew, whose goal was to restore the reputation of Chopin and his music, after overhearing a conversation between piano students denigrating Chopin’s music as “boring and obsolete”, “effeminate and unhealthy” and “unnecessarily sentimental”. 1

It is also somewhat counter-intuitive to search for promising pianists with an all-Chopin (or Chopin-only) repertoire. If that’s the sole purpose of the competition, it could have easily been another Tchaikovsky competition, where participants are expected to present an all-rounded programme. On the other hand, there must have been some reasons behind the choice of repertoire, even at the risk of causing fatigue to both the listeners and the jury. For example, Ballade No. 4 in F minor and Etude in G-sharp minor, Op. 25 No. 6 were played 18 times in the first round this year! 2

Yulianna Avdeeva © Sammy Hart

It requires a unique musical approach and temperament to realise Chopin’s musical intention and imagination. Of course, one needs an exceptionally high degree of technical prowess and dexterity, as in any other repertoire. This, however, doesn’t guarantee that he or she will be a great Chopinist. In my humble opinion, a Chopinist should possess a deep understanding of the dance forms that Chopin integrated into his works, naturalness and poetry, achieving a fine balance between classicism and romanticism. Even more importantly, the interpretation should be in line with Chopin’s ethos. For example, would it be appropriate to bring out the superficial brilliance but not the pathos in his music? Would it be acceptable to neglect the underlying dancing pulse, like Krakowiak in the third movement of his Piano Concerto No. 1?

Talking about Chopinistic qualities, one cannot avoid touching upon the idea of originality. Undoubtedly, no one would like to hear a “museum” interpretation that lacks personal insight or investment. Meanwhile, there’s a distinction between being original and being stylistically inappropriate. This fine line varies from musician to musician, but I never find being original merely for the sake of being different from others agreeable. For instance, going against the composer’s indications doesn’t necessarily make one a creative musician.

Note how the winner of Chopin Competition 2010, Yulianna Avdeeva, masterfully emphasised the mazurka pulse in the Scherzo (7:25) of Chopin’s Second Piano Sonata. This was based on the accent Chopin notated on the third beat, but seldom do pianists give it due attention like Avdeeva.

Yulianna Avdeeva – Chopin: Sonata in B flat minor, Op. 35 (third stage, 2010)

Another example would be Grigory Sokolov’s rendition of Chopin Prelude Op. 28 No. 24 in D minor. He self-prescribed a diminuendo near the apocalyptic ending to create momentary calmness before the storm, further intensifying the drama and reinforcing the imagery of the music.

Frédéric Chopin: 24 Preludes, Op. 28 – No. 24 in D Minor (Grigory Sokolov, piano)

Krystian Zimerman © Mark Allan

The indisputable winner in 1975, Krystian Zimerman was also incredibly original in his recording of Chopin Piano Concertos with the Polish Festival Orchestra, conducted by Zimerman himself. Just listen to the first few bars, and you’ll understand me. Chopin has long been criticised for his orchestration, but Zimerman worked thoroughly with the orchestra and teased out so many previously unheard nuances. Typically executed in a rather uninspired manner, the orchestral introduction was finally done justice here with Zimerman’s immaculate attention to details and uncompromising character.

Frédéric Chopin: Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op.11 – I. Allegro maestoso (Krystian Zimerman, piano/cond.; Polish Festival Orchestra)

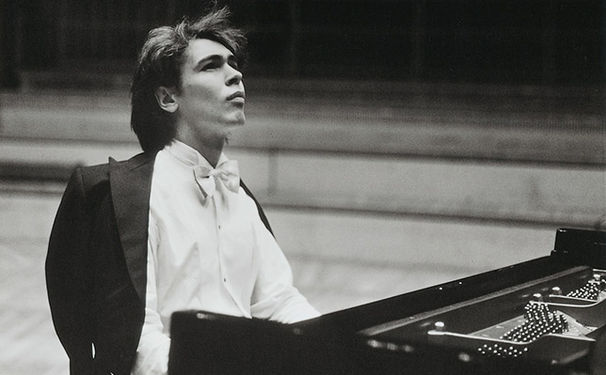

Ivo Pogorelich in 1987 © Susesch Bayat

Maybe you don’t agree with the above qualities I look for, since the term Chopinist alone can already split music lovers or even the jury (hence the controversies Ivo Pogorelich raised in 1980). Nevertheless, I believe you will still agree that playing Chopin well demands a different aspect of music-making. A real Chopinist is usually, if not always, a great pianist, but the opposite may not hold true.

Sometimes we may be intoxicated by the technical wizardry displayed by the participants, especially during the hype of the Competition. It’s yet a better idea to sit down and re-think — what should be the primary aim of the Chopin Competition?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

1 http://chopinreview.com/pages/issue/7/1

2 https://chopin2020.pl/en/news/article/237/and-the-winners-are…-ballade-in-f-minor,-op.-52-and-etude-in-g-sharp-minor-op.-25-no.-6!

Excellent observations, especially that a great Chopinist needs to be a great pianist, but that the converse need not be true. Hence, the unique mandate of the Chopin Competition, compared to other competitions.

As well, I appreciate your comment on originality. Works of genius composers are sufficiently rich in undiscovered original possibilities that it is only but a rare exception (arguably, if ever) that a performer’s so-called “originality” is ever comparable to a composer’s, such as Chopin’s.