“Minors of the Majors” invites you to discover compositions by the great classical composers that for one reason or another have not reached the musical mainstream. Please enjoy, and keep listening!

“Minors of the Majors” invites you to discover compositions by the great classical composers that for one reason or another have not reached the musical mainstream. Please enjoy, and keep listening!

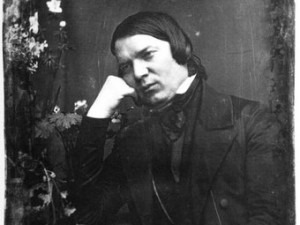

Here then is the question of the day. How much of Robert Schumann’s music do you actually know? Well, there is the piano concerto, a substantial number of pieces for solo piano, the song-cycle Dichterliebe, selected chamber compositions and surely you have heard a symphony or two. But how about the opera Genoveva, the oratorio Paradis und Peri, the Choral Ballads, the late songs and late piano pieces or the Requiem? Fact is, about a third of Schumann’s output is standard concert fare, a third is heard occasionally, and a third is practically unknown. Particularly his late works are almost exclusively placed within the context of his mental illness. However, when we hear his music without the attached baggage of his medical history, we quickly understand the truly experimental nature of his musical thoughts. In terms of harmony, rhythm and emotion Schumann was way ahead of his time, and judging by the number of unknown works, he still is!

Robert Schumann: Introduction and Concert Allegro, Op. 134

Take for example the 12 minutes Introduction and Concert Allegro, Op. 134. This last Schumann work for piano and orchestra was an anniversary present for his wife Clara in 1853, and it is dedicated to Johannes Brahms who visited the Schumann’s during that time. The emphasis is entirely on the piano with the orchestra relegated to an accompanying role. Almost a concerto in itself, it resembles the curious mixture of symphony, concerto and grand sonata that Schumann had concocted in his earlier piano concerto. The slow introduction gives way to a furious “Allegro,” that is primarily a vehicle for the solo pianist. Since it was written for Clara, it’s not surprising that an extended cadenza forms an integral part of the “Allegro.” Highly virtuosic, the music is grimly obsessive about controlling a brief two-note motive that dominates the music. While some writers have connected this musical obsession with Schumann’s illness, we could certainly argue that Schumann was merely searching for a new simplicity in the Romantic Movement. Regardless in what context we hear Schumann’s music, we should marvel at the power of his imagination and the brilliance of his mind!

You May Also Like

- Minors of the Majors

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart:

Les petits riens (The Small Things), K. 299b After crisscrossing Europe in an almost desperate search for gainful employment, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was eventually appointed official court composer in Vienna. - Minors of the Majors

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Suite in D minor In 2002, scholars found an unknown four-movement composition by Rachmaninoff in the depths of the Glinka Museum Archives in Moscow. - Minors of the Majors

Modest Mussorgsky: Dawn on the Moscow River Impoverished and evicted from his flat for failure to pay rent, Modest Mussorgsky once again sought refuge in the bottle. - Minors of the Majors

Jean Sibelius: Ödlan (The Lizard) Starting in 1898, Jean Sibelius regularly wrote incidental music to accompany productions of staged drama.

More Anecdotes

- Bach Babies in Music

Regina Susanna Bach (1742-1809) Learn about Bach's youngest surviving child - Bach Babies in Music

Johanna Carolina Bach (1737-81) Discover how family and crisis intersected in Bach's world - Bach Babies in Music

Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782) From Soho to the royal court: Johann Christian Bach's London success story - A Tour of Boston, 1924

Vernon Duke’s Homage to Boston Listen to pianist Scott Dunn bring this musical postcard to life