“Minors of the Majors” invites you to discover compositions by the great classical composers that for one reason or another have not reached the musical mainstream. Please enjoy, and keep listening!

“Minors of the Majors” invites you to discover compositions by the great classical composers that for one reason or another have not reached the musical mainstream. Please enjoy, and keep listening!

Camille Saint-Saëns was one of the greatest of all music prodigies. He produced his first composition at age 3, and publically performed a Beethoven violin sonata at age 4. In a legendary concert at the Salle Pleyel, and at the tender age of 10, he offered to play as an encore any of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas from memory. Berlioz admiringly wrote, “This young man knows everything, and he is an absolutely shattering master pianist.” Franz Liszt declared him “the world’s greatest organist,” but underestimating his own achievements as a composer, Saint-Saëns modestly suggested that he rated “First among composers of the second rank.” He clearly possessed a mastery of compositional technique, and his ease, ingenuity, naturalness and productivity was compared to “a tree producing leaves.” Yet, during a period of extreme musical experimentations, Saint-Saëns remained stubbornly traditional, and by the time of his death in 1921, his compositional style was considered deliberately old fashioned. Scathing critical opinion suggested “Saint-Saëns has written more rubbish than any one I can think of. It is the worst, most rubbishy kind of rubbish.”

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns: Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 119

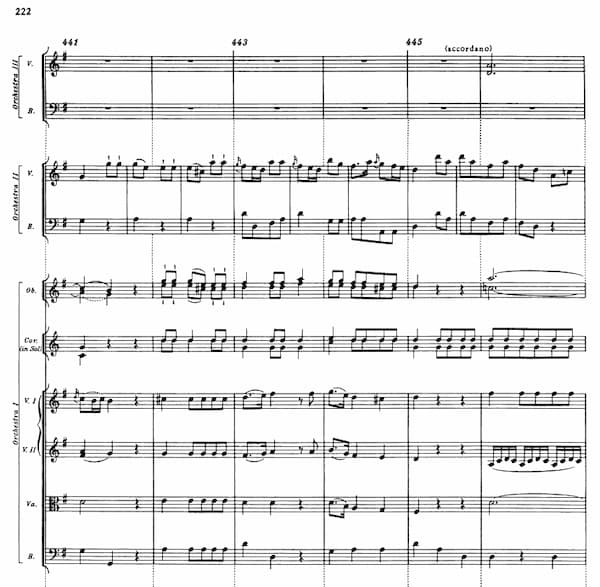

Among his most rubbished works is the Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, written in 1902 for the cellist Josef Hollman. Stylistic reasons might certainly be partially to blame for this neglect, but Saint-Saëns himself observed that the Second Cello Concerto “will never be as well-known as the First: it simply is too difficult.” In fact, the score abounds with treacherous double-stops and firework passages reaching into the highest register of the instrument. Although it is cast in a traditional three-movement layout, the work unfolds in a continuous flow, providing a single unified entity. The composition is cyclically linked, with the finale—immediately following a fiendishly difficult cadenza—restating the first thematic group of the opening section. Although a critic barked, “never have so many notes been written to so little purpose,” the work radiates Saint-Saëns’ unmistakable melodic charm and characteristic freshness and vitality.

You May Also Like

- Minors of the Majors

Max Bruch: Concerto for Clarinet and Viola in E minor, Op. 88 Celebrating his 75th birthday in 1906, the legendary violinist Joseph Joachim declared that Germany had four great violin concertos. - Minors of the Majors

Dimitri Shostakovich: Suite for Variety Orchestra In the immediate aftermath of WWI, Western Europe fell under the spell of popular American musical styles. - Minors of the Majors

Johannes Brahms: Piano Trio in A Major, Op. posth. Johannes Brahms was an uncompromising perfectionist. - Minors of the Majors

Frédéric Chopin: Grand Duo Concertant Chopin arrived in Paris in the middle of September 1831, and quickly struck up a close friendship with the cellist and composer Auguste Franchomme.

More Anecdotes

- Bach Babies in Music

Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach (1732-95) Read about the artistic collaboration from the Bach family -

Mozart Makes Another Quodlibet Mozart intentionally wrote harmonic "mistakes" in Don Giovanni!

Mozart Makes Another Quodlibet Mozart intentionally wrote harmonic "mistakes" in Don Giovanni! - Bach Babies in Music

Christiana Dorothea Bach (1731-32) Christiana Dorothea lived only 17 months, discover her story - Bach Babies in Music

Christiana Benedicta (1729-30) Little Christiana Benedicta lived only four days. Find out more