Gustav Mahler was born in 1860 in Jihlava, present-day Czech Republic. He became one of his generation’s most famous symphonists.

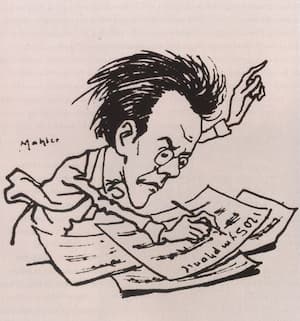

Gustav Mahler

Here are a few facts about Mahler’s life and career:

- Mahler is best known for his symphonic works, which are typically longer and more expansive than those of his contemporaries. He famously said, “A symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything.”

- In his work, Mahler grappled with multiple personal issues: his traumatic death-filled childhood – the death of his young daughter – the affair of his notoriously beautiful wife and muse Alma – and the health troubles that would ultimately kill him.

- Mahler was a master conductor in addition to a great composer, and his mastery of the orchestra was second to none. He expanded the traditional orchestral palette by experimenting with unconventional combinations of musical instruments. This gave his music a distinctive and richly coloured sound.

Mahler’s works are so big that they’re impossible to summarize in a few sentences. But don’t worry: we’ll lay out the basics for you.

Without any further ado, here are seven pieces by Gustav Mahler to enjoy:

Piano Quartet in A minor (1876)

Mahler wrote this work as a teenager. He never finished it, so we only have this one movement. But that one movement is gorgeous.

Even though this quartet is on a much smaller scale than his later sprawling works, its intense personal vulnerability and long, elaborate lines anticipate his future output.

Symphony No. 1 in D (1887-88)

Mahler was 27 and an ambitious second conductor at the Leipzig Opera when he wrote his first symphony.

From the beginning, Mahler was unsure about what exactly he wanted this piece to be.

He initially described it as a tone poem, a label that would suggest it had some kind of extra-musical program.

But over the course of many revisions, he hedged his bets by calling it a “Tone Poem in the Form of a Symphony.”

No matter what his initial intentions were, the beginning of Mahler’s First symphony was clearly inspired by nature. We can hear shepherds, cuckoo calls, and more. A rustic scherzo calls to mind a dance from rural Austria.

One of the most striking moments of the symphony is in the third movement, which features a twisted re-imagining of the children’s song Frère Jacques.

One of the inspirations for the symphony was reportedly an 1850s woodcut that features the funeral procession of a hunter…followed by celebrating animals.

Symphony No. 2 (1888-94)

As large in scope as his first symphony was, Mahler’s second symphony was even bigger. It lasted for ninety minutes and was written for a massive symphony orchestra and chorus. (That said, the chorus doesn’t actually sing until toward the end.)

The opening movement was originally a tone poem (sound familiar?) called Totenfeier, or “Funeral Rites.” It is a dramatic funeral march, and includes allusions to the Dies Irae plainchant often associated with death.

The second movement is a lilting Austrian dance. It’s so refined after the sheer brutality of the first movement that it almost comes across as sarcastic.

The third movement is a bitter scherzo featuring prominent timpani booms. It always seems a little off-balance, as if the orchestra is a little drunk.

The fourth movement contains a lovely song performed by an alto soloist whose voice rises from the orchestral texture like an unexpected angel.

The fifth and final movement sets this symphony apart from the rest. It starts almost a full hour into the work and lasts for thirty minutes. Here, the chorus finally has its glorious say, and hearing it live is one of the most spiritual experiences one can have in a concert hall. All of the voices sing at triumphant full strength, backed up by a massive symphony orchestra and clanging bells.

Symphony No. 5 (1901-02)

The entirety of Mahler’s fifth symphony is worth listening to; it’s one of his most accessible works.

However, its fourth movement has taken on a life of its own as a concert piece that is sometimes programmed even apart from the symphony. It’s known simply as the Adagietto.

It is written for just strings and harp, and it’s absolutely heartrending. Legend has it, it’s a love song for his new wife Alma. Alma herself claimed that he gave a poem to go with the music:

In which way I love you, my sunbeam,

I cannot tell you with words.

Only my longing, my love and my bliss

can I with anguish declare.

(Alma was not always the most reliable narrator, so we can’t know for sure if any of this is true, but it’s a lovely story.)

Despite its connection with romantic and even erotic love, the movement has also gained connotations of tragedy.

Influential conductor Leonard Bernstein conducted the Adagietto at the funeral mass of Robert F. Kennedy after his assassination in 1968. It was also often heard in America after the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

Whether it calls to mind the anguish of love, death, or both, it is a piece that has become dear to millions.

Kindertotenlieder (1901-04)

Kindertotenlieder translated means “Songs on the Death of Children.” It’s a song cycle for voice and orchestra that draws on the work of Friedrich Rückert, who wrote poetry after his two young children died of scarlet fever.

Gustav Mahler and Alma Schindler

The subject of child death was deeply familiar to Mahler. When he was young, no fewer than eight of his thirteen siblings died, and he remembered his childhood as an unbearable parade of coffins.

He composed some of the songs in 1901, but progress stalled partway through. In 1904, he picked the songs up again. Alma was furious, terrified that her husband was tempting fate, given that they had two young daughters.

In 1907, the Mahlers’ daughter Maria died of scarlet fever. The coincidence was terrifying. Afterwards, Mahler wrote simply, “When I really lost my daughter, I could not have written these songs any more.”

Symphony No. 6 in A minor (1903-04)

The Symphony No. 6 is one of Mahler’s most violent, terrifying works. Although nobody knows for sure how it got this nickname, it’s commonly known as the Tragic, and for good reason. It is relentless – but also terrifyingly captivating.

Aside from its aggressive drama, this work is probably best known for its massive percussion section.

That includes an instrument known as the Mahler Hammer, built specifically for this work to carry out the composer’s wishes for a sound in the last movement that was “brief and mighty, but dull in resonance and with a non-metallic character (like the fall of an axe).”

Mahler continued revising the symphony for years, as he did with many of his works. One interesting change is that the symphony originally featured five blows of the Mahler hammer in the finale. Later he decreased that to three, and then to just two.

Alma claimed that the three hammer blows were blows of fate meant to represent her husband’s acrimonious departure from the prestigious Vienna Opera, the diagnosis of his fatal heart condition, and the death of their daughter.

That said, we can’t know for sure if this is what he actually had in mind, since Alma was, again, a notoriously unreliable narrator.

Symphony No. 8 in E-flat (1906)

Mahler’s creative ambitions, already massive, only continued to grow.

In 1906, he wrote his eighth symphony for woodwinds, brass, percussion, bells, tam-tam, celesta, piano, organ, mandolin, harps, strings, multiple solos, two adult choirs, and a children’s choir. It won’t surprise you to hear that the symphony earned the nickname Symphony of a Thousand!

Gustav Mahler © Mahler Foundation

He reported to a friend, “This Eighth Symphony is remarkable for the fact that it unites two poems in two different languages, the first being a Latin hymn and the second nothing less than the final scene of the second part of Faust. Does that astonish you?”

The eighth symphony continues in this all-encompassing vein, making it impossible to summarise in a few sentences. But it’s one of the most striking works in the entire classical music repertoire, and you should check it out, especially if you love singing or big works! Because symphonies don’t get much bigger than this.

The final words of the symphony are famous:

All things transitory

Are only symbols;

What is insufficient,

Here becomes an event;

The indescribable

Here is accomplished;

The eternal feminine

Pulls us upwards.

Conclusion

After being pushed out of prestigious posts in Europe, Gustav Mahler took jobs in America conducting at the New York Philharmonic and the Metropolitan Opera.

During the 1910/11 concert season, he became ill and developed bacterial endocarditis, an infection that people with heart issues are especially prone to.

The family returned to Europe to seek medical care in Paris and Vienna, but he died in May 1911. He was fifty years old.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter