Gustav Mahler and Thomas Mann

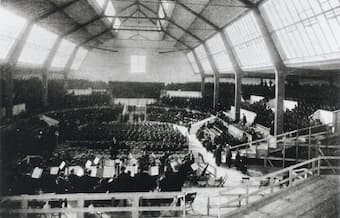

On 12 September 1910, audiences in Munich were treated to a unique classical music extravaganza. For the premiere of his 8th Symphony, Gustav Mahler had assembled a performing cast that stretched the resources to their limits. It involved 858 singers, both soloists and three choruses, an orchestra of 171 members and Mahler conducting. In all, we are talking a total of about 1030 musicians involved. As such, it is hardly surprising that the concert impresario Emil Gutman coined the name “Symphony of a Thousand,” a sobriquet Mahler quickly rejected. For once, however, this concert proved an unmitigated success for Mahler, undoubtedly the greatest triumph in his career. What made it even more special was the fact that many of the leading intellectual and cultural figures of Europe were present. The literary great Thomas Mann, for one, remarked that Mahler is “the man who expressed the art of our time in its most profound and sacred form.” Initially, however, Mahler had struggled with two weeks of creative paralysis once the family arrived in Maiernigg for their annual summer holiday in 1906. It was purely by accident, although Alma Mahler would subsequently provide a slightly different scenario, Mahler stumbled upon the Pentecostal hymn “Veni Creator Spiritus” (Come, Creator Spirit.)

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Part I “Veni, creator spiritus” (Mimi Coertse, soprano; Hilde Zadek, soprano; Ira Malaniuk, alto; Lucretia West, alto; Giuseppe Zampieri, tenor; Hermann Prey, baritone; Otto Edelmann, bass; Vienna Boys Choir; Wiener Singverein; Konzertvereinigung Wiener Staatsopernchor; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Dimitri Mitropoulos, cond.)

Premiere of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8

Swept away on a tide of great inspiration, Mahler feverishly worked on a composition “to which all my previous symphonies are merely preludes.” At some point, the final scene from Goethe’s Faust provided the inspiration for a complimentary second part, and after merely eight weeks he had finished a musical draft that fused and synthesized elements from the symphony, the oratorio and from music drama with the mysteries of redemption. Justifiably proud, he reported to Richard Specht in August 1906 “I have never composed anything like this. In content and style it is altogether different from all my other works, and it is surely my greatest accomplishment… Its form is something altogether new. Can you imagine a symphony that is sung throughout, from beginning to end?… The whole first movement is strictly symphonic in form yet is completely sung; it is simplicity itself. It is a ‘True Symphony,’ in which the most beautiful instrument of all is led to its calling.” With his Eighth Symphony, Mahler had created a work that was, and still is, unique within the entire symphonic literature.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Part II “Final Scene from Faust” – Poco adagio (London Philharmonic Orchestra; Vladimir Jurowski, cond.)

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Part II “Final Scene from Faust” – Waldung, sie schwankt heran (London Philharmonic Choir; London Symphony Chorus; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Vladimir Jurowski, cond.)

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Part II “Final Scene from Faust” – Wie Felsenabgrund mir zu Füssen (Matthew Rose, bass; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Vladimir Jurowski, cond.)

Rehearsal for the symphony

By joining the orthodox Christian’s humble prayer for the enlightenment of Pentecost with the iconic and metaphysical symbol of questing humanity contained in Faust, Mahler was undoubtedly giving voice to the longings of his age. In its liturgical treatment, the original seven verses of “Veni Creator Spiritus” have symbolic meaning as an allusion to the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit. Removed from its liturgical context, Mahler’s setting became a “great shout by humanity to the skies for the creative vision that the modern world so desperately needs.” Concurrently, Mahler regarded Faust as a spiritual document. Since the protagonist exchanges his soul for unlimited human knowledge and worldly pleasures, every writer dramatizing the story condemned Faust to eternal damnation in Hell. Yet in Goethe’s humanistic hands, he manages to escape the clutches of damnation and find redemption through divine love. In a letter to Alma, Mahler explained his understanding of Goethe’s philosophy: “The essence of it is really Goethe’s idea that all love is generative, creative… You have it in the last scene of Faust, presented symbolically.” This notion of divine love and creative spirit as the cumulative ultimate powers of the universe is readily found in both the ecclesiastical and the humanistic text.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Part II “Final Scene from Faust” – Höchste Herrscherin der Welt! (Barry Banks, baritone; London Philharmonic Choir; London Symphony Chorus; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Vladimir Jurowski, cond.)

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Part II “Final Scene from Faust” – Komm! Hebe dich zu höhern Sphären! – Blicket auf zum Retterblick, alle reuig Zarten (Sofia Fomina, soprano; Barry Banks, baritone; Matthew Rose, bass; Tiffin Boys Choir; Clare College Choir, Cambridge; London Philharmonic Choir; London Symphony Chorus; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Vladimir Jurowski, cond.)

Originally, Mahler conceived his Eight Symphony in four movements, with the setting of the hymn becoming the extended symphonic first movement. The Faust text, in turn, corresponded to a slow movement, a scherzo and a finale, respectively. Without abandoning this original concept, Mahler eventually synthesized the three Faust sections into a seamless single movement of enormous emotional range. The musical setting of the hymn keeps entirely with the symphonic tradition, and presents primary and secondary thematic materials that undergo transformation and development. A grotesquely distorted version of the opening march stands at the beginning of the development proper, and a greatly condensed recapitulation swiftly progresses towards a jubilant coda. In the literary original, the concluding scene from Faust is set in mountain gorges inhabited by hermits. It is therefore hardly surprising that Mahler opens Part II with a broadly drawn prelude evoking a mysterious and mystical wilderness. Subsequently, a variety of themes and motives brush away the musical memories of mortality. The final chorale, the “Chorus Mysticus” begins in hushed awe and reverence, but ends in a blaze of luminous sound. The entire orchestra restates the “Veni, Creator Spiritus” theme in the coda. Mahler had ingeniously referenced the basic poetic ideas in Faust—eternal love, divine grace, earthly inadequacy and spiritual reincarnation—and by connecting it to the Latin Pentecost hymn “drawn a direct line from earthly existence into the primeval light of divine strength of love.”

Originally, Mahler conceived his Eight Symphony in four movements, with the setting of the hymn becoming the extended symphonic first movement. The Faust text, in turn, corresponded to a slow movement, a scherzo and a finale, respectively. Without abandoning this original concept, Mahler eventually synthesized the three Faust sections into a seamless single movement of enormous emotional range. The musical setting of the hymn keeps entirely with the symphonic tradition, and presents primary and secondary thematic materials that undergo transformation and development. A grotesquely distorted version of the opening march stands at the beginning of the development proper, and a greatly condensed recapitulation swiftly progresses towards a jubilant coda. In the literary original, the concluding scene from Faust is set in mountain gorges inhabited by hermits. It is therefore hardly surprising that Mahler opens Part II with a broadly drawn prelude evoking a mysterious and mystical wilderness. Subsequently, a variety of themes and motives brush away the musical memories of mortality. The final chorale, the “Chorus Mysticus” begins in hushed awe and reverence, but ends in a blaze of luminous sound. The entire orchestra restates the “Veni, Creator Spiritus” theme in the coda. Mahler had ingeniously referenced the basic poetic ideas in Faust—eternal love, divine grace, earthly inadequacy and spiritual reincarnation—and by connecting it to the Latin Pentecost hymn “drawn a direct line from earthly existence into the primeval light of divine strength of love.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Part II: Final Scene from Faust, “Chorus Mysticus”