In the aftermath of a performance of Richard Wagner’s Tannhäuser in 1861, everybody tried to figure out what the so-called “Music of the Future” was all about. Many critics mock Wagner for trying to depict absurd narrative details and even material objects in music. A critic writes, “Wagner makes impossible expressive demands on his famously absolute music; he required the hermeneutic assistance of his operatic characters; the characters themselves were reduced to cyphers.” And another critic added, “by wanting to reduce lyric characters to a state of abstraction is quite simply to destroy opera rather than regenerate it; it is to make the singers into machines or, if you will, living program notes.” “50 years on this path from now,” a critic writes, “and music will be dead because we have killed melody, and melody is the soul of music.”

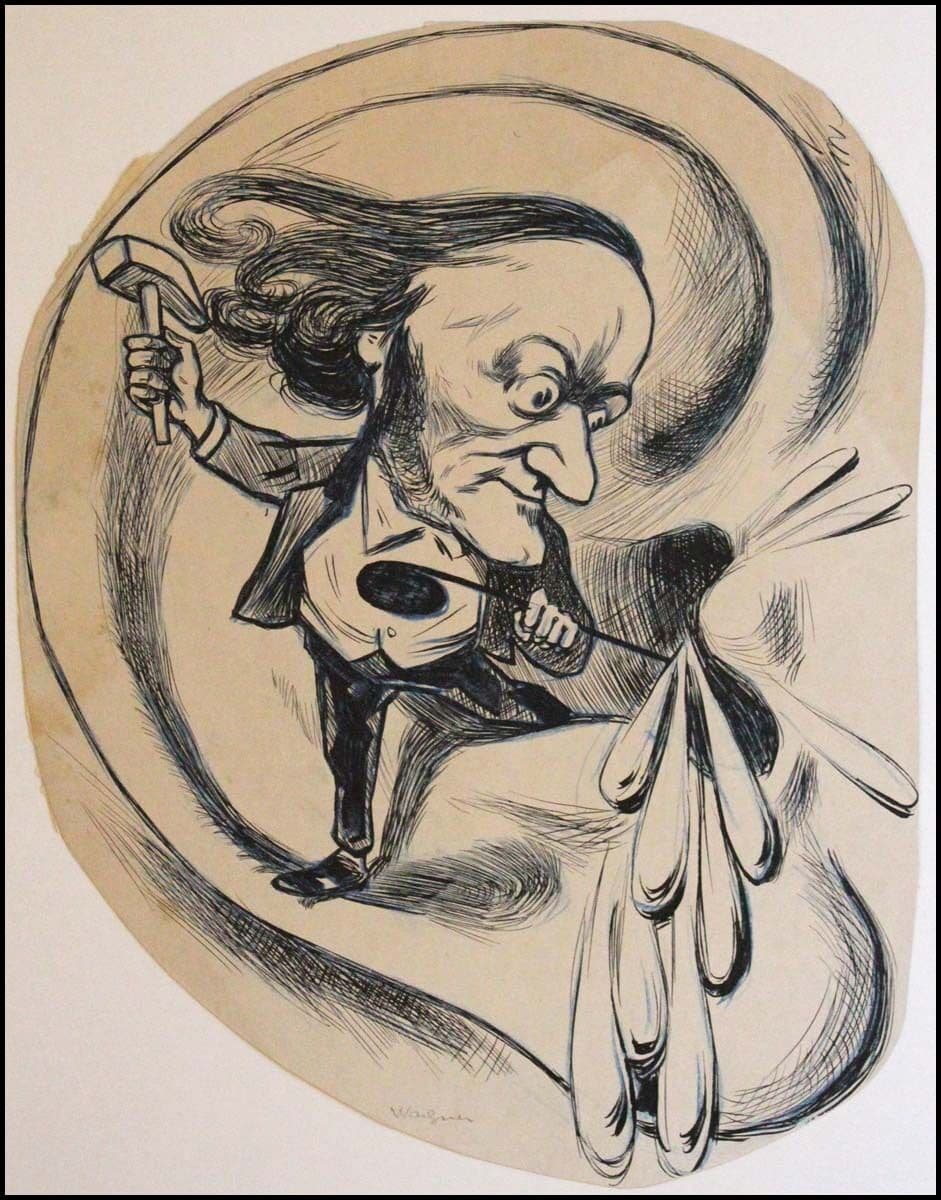

Richard Wagner smashing the eardrum of the world

However, criticism was not confined to the written word; the “Music of the Future” was lampooned on the musical stages as well.

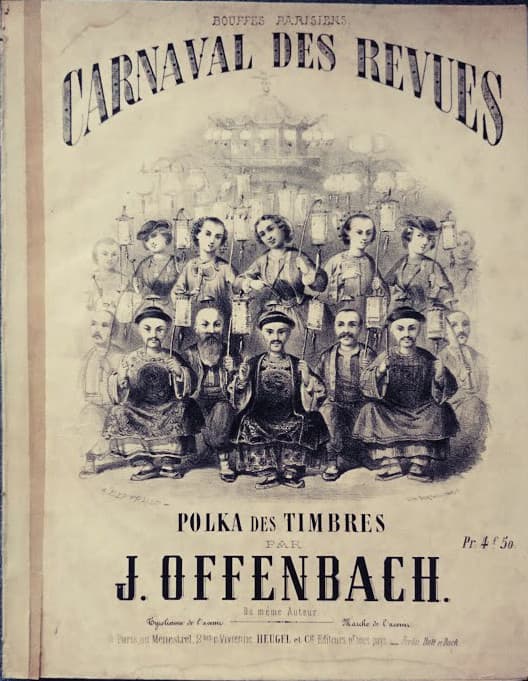

Jacques Offenbach: Le carnival des revues, “Symphonie de l’avenir” (Laurent Naouri, bass; Les Musiciens du Louvre; Marc Minkowski, cond.)

Jacques Offenbach: Le carnival des revues

Jacques Offenbach was no friend of Wagner’s music or aesthetics, and his Le Carnaval des revues opened on 10 February 1860. A satirical take on the traditional revue format, Le Carnaval offers a prologue and nine tableaux that lampooned various aspects of Parisian theatrical life. The tension between older operatic repertoire and the “music of the future” forms the subject of the sixth tableau and features two specifically composed numbers. This particular scene depicts a meeting on Champs Elysées between four canonic composers of the past, Grétry, Gluck, Mozart, and Weber. This happy scene is interrupted by several comic intrusions. First, we meet an aspiring composer who complains that with all the ancient works on stage in the city, he can’t get his opera performed. A comically voiced German then praises Meyerbeer’s virtues, and finally making the noisiest entrance of all, comes “Le Compositeur de l’avenir.” He proclaims his revolutionary presence and the destruction of the music past. He then conducts an impromptu performance of one of his compositions: a “Marche des fiancés,” later renamed “La Symphonie de l’avenir,” before he is being chased from the scene.

Jacques Offenbach: Die Rheinnixen, “Overture” (Leipzig Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Krüger, cond.)

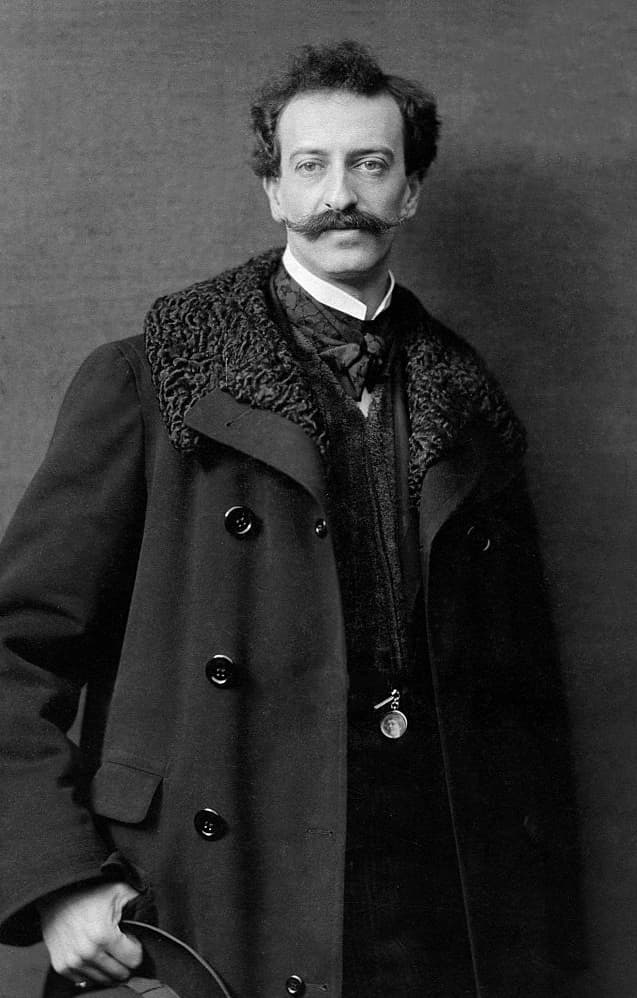

Jacques Offenbach, c. 1865

A scholar writes, “Offenbach’s satire is by any measure a piece of musical ephemera; but it is nevertheless striking in the ambiguity of its relationship to its musical target. It raises important questions about how Wagner’s “music of the future” might have been perceived in 1860. Offenbach’s “Symphonie” is not simply a response but also a contribution—however parodic—to an imagined corpus of “music of the future.” Offenbach clearly makes no attempts to quote from Wagner’s compositions literally, and it is unlikely that he had heard much of Wagner’s music before 1860. One thing for sure, Offenbach could not have known Wagner’s “Rheingold” when he composed his “Die Rheinnixen” in 1864. Commissioned by the Vienna Court Opera it features a libretto of elves, fairies, knights, and the water sprites of the Rhine. Running short of time, Offenbach cobbled together various fragments from earlier works, and the production lasted just one performance. However, the really catchy overture later resurfaced as the “Barcarolle” in The Tales of Hoffmann.

Franz von Suppé: Lohengelb oder Die Jungfrau v. Dragant, “Liebeswalzer” (Slovak State Philharmonic Orchestra, Košice; Christian Pollack, cond.)

Offenbach was hardly the only composer of light music to parody Richard Wagner.

Emilie Bieber: Franz von Suppé (Austrian National Library)

Franz von Suppé produced his Lohengelb oder Die Jungfrau von Dragant in 1870. The libretto by Karl Costa and Mortiz Anton Grandjean is based on a parody entitled “Lohengelb” by Johann Nestory. However, the work is essentially a parody of Lohengrin by Richard Wagner, centered on the knight of the Grail whose name suggests “Flame-Green,” and the maid of Brabant. “Blaze-yellow” enters the scene to defend the honor of Elsa, the daughter of the late Duke of Dragant. She is accused of having killed Prince Pafnuzzi, brother of Knight Mordigall von Wetterschlund. Knight Mordigall calls for a duel, and Flame-yellow appears on a chariot pulled by a white sheep. He offers to duel for Elsa, and asks her hand in marriage under the condition that she is not allowed to ask for his name or origin. Blaze-yellow defeats Knight Mordigall, but spares his life. Mordigall is humiliated and sneaks away with his wife, Gertrud, a well-known witch; both swear bitter revenge.

Franz von Suppé: Lohengelb oder Die Jungfrau v. Dragant, “Mörderduett”

Everybody is celebrating the restored honour and the upcoming wedding of Elsa, but Gertrud hatches a cunning plan. Knight Mordigall is supposed to accuse the knight of being a magician, while she will speak with Elsa to cast doubt on Blaze-yellow’s name and origin. The next morning, Gertrud calls Blaze-yellow a question mark while Mordigall presents his charge of sorcery. Since Blaze-yellow arrived on an innocent lamb, the accusation is dismissed, and now Mordigall and Gertrud, together with a henchman are plotting murder. After the wedding, Elsa can’t hold her tongue and complains that she does not know the name of her husband and asks the forbidden question. The attempted murder, meanwhile, is repelled, and Mordigall loses his head. The next morning, the wedding guests are disturbed by the story of the nightly fight and by the fact that the strange knight announces that he has to move away. He confesses that he is a Knight of the Holy Grail, that his name is Blaze-yellow and that he was only on a holiday trip. Gertrud confesses that she earlier turned Elsa’s brother into a sheep. When the Holy Grail arrives in person, he breaks the spell and the sheep becomes the prince again. Gertrud is forgiven, and Mordigall is returned to life sporting a new head. The Holy Grail also releases Blaze-yellow, who is now allowed to remain with Elsa.

Franz von Suppé: Lohengelb oder Die Jungfrau v. Dragant, Terzett: “Wie wir drei uns so schön verstehn”

Oscar Straus, 1907

Satirical works lampooning Richard Wagner continued to appear on stage well after the composer’s death. In 1904, Oscar Straus presented an affectionate persiflage entitled “Die lustigen Nibelungen” (Merry Nibelungs). It first played on 12 November 1904 in Vienna, and scored a resounding hit in Berlin. “Every punch-line was laughed at, and every musical allusion understood. There was laughter at dragon-blood sausages and the dachshund dressed as a dragon, and at the parody of the Nibelung verse meter.” The text originated with Rideamus, the pseudonym of Fritz Oliven, and featured a terrified King Gunther of Burgundy. He had invited Queen Brunhilde of Isenland to a fight at his court. If he wins this duel, the prize is marriage to her, but so far, Brunhilde has killed all her suitors. The dragon slayer Siegfried von Niederland has already defeated Brunhild once, and since he has just started an affair with Kriemhild, Gunter’s sister, the King asks him for help.

Oscar Straus: Die lustigen Nibelungen, “Excerpts”

In Act 2, the double wedding has taken place, but amidst wild celebration, the first marital conflict ensues. On her wedding night, Brunhild defeats Gunter in a wrestling match and hangs him on the coat hooks in front of her bedroom door. Siegfried has to step in again, but when the swindle is revealed that it is not husband Gunther but Siegfried who makes Brunhild happy at night, Hagen is given the task of getting Siegfried out of the way.

But the sudden drop in the price of the Nibelungen shares makes Hagen’s action seem pointless. In the end, they agree on a harmonious love triangle and bring the story to its happy conclusion. Soon after its enormous Berlin success, the Merry Nibelungs played on a number of German-speaking stages, but in 1908, “German nationalist circles put out a newspaper call in protest.” They felt insulted and protested against “the mockery of our people’s most splendid possession, our Nibelung saga, the mightiest work of world literature in general.” A number of theatres had planned to stage the successful new operetta, but when they experienced violent demonstrations, nobody dared to put the Merry Nibelungs on stage. A scholar writes, “even during Wagner’s lifetime, there was resistance to his egomaniacal ambition as well as the self-evident and, to some, crushing profundity of his work.” That resistance, for a whole host of reasons beyond music, continued well into the 20th century. However, Wagner did get his revenge as he basically infiltrated every phase of movie history, from the silent era to superhero blockbusters.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Oscar Straus: Die lustigen Nibelungen – Act III: Round Dance: Nun so lasst uns denn Siegfried ermorden … (Gunther, Ute, Dankwart, Volker, Giselher, Kriemhild, Hagen, Brunhilde) (Martin Gantner, baritone; Daphne Evangelatos, mezzo-soprano; Gerd Grochowski, vocals; Heinz Heidbuchel, vocals; Gabriele Henkel, vocals; Lisa Griffith, soprano; Josef Otten, vocals; Gudrun Volkert, soprano; Cologne Radio Orchestra; Siegfried Köhler, cond.)