While the televisions of the world are squarely aimed at the New Year’s Concert of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, a fresh take on this celebration will take place at the Ehrbar Saal in Vienna. A newly founded chamber ensemble made up of the women in the Vienna Philharmonic will present a selection of repertoire equally divided between works by male and female composers.

La Philharmonica

The new ensemble is called “La Philharmonica,” and features six top musicians from the ranks of the Vienna Philharmonic who come together in an exciting combination of string and woodwind instruments. The project is the brainchild of musicologist Irene Suchy, and the purpose of the concert is to “make a clear statement right from the start… that the work of female composers is played far too rarely.”

Ehrbar Saal

I think it’s a fabulous idea, so let’s help and promote this fresh take on the Vienna New Year’s Concert. Many of the featured female composers are not well known, and their music has long been neglected. It’s high time to get to know these talented women, don’t you think?

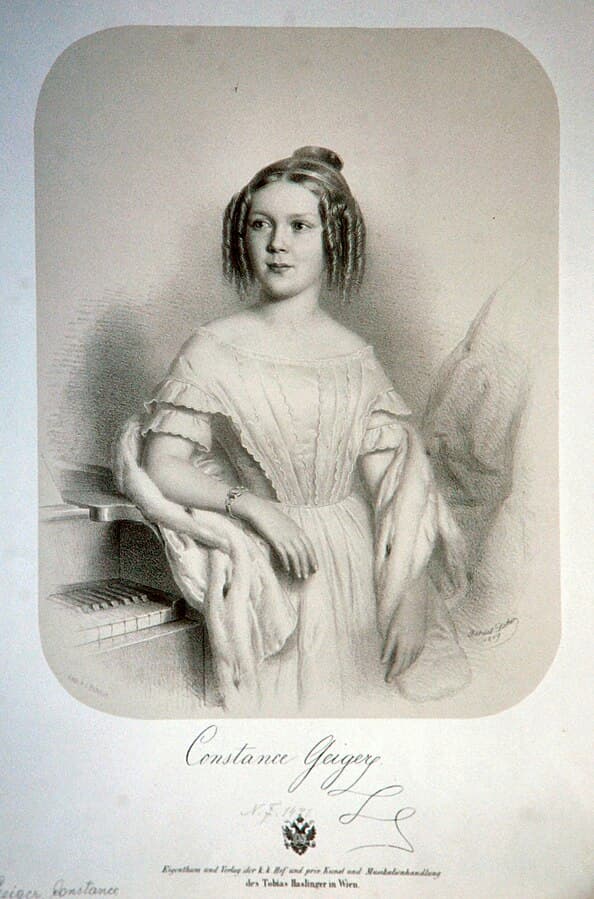

Constanze Geiger

Compositions by Constanze Geiger

Constanze Geiger von Ruttenstein (1835-1890) will be the first female composer featured in the New Year’s Concert of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. That annual concert has not featured a work by a woman in its 81-year history. In 2025, however, Geiger will receive double exposure as her music will also feature in the La Philharmonica celebration.

Geiger was an Austrian pianist, composer, singer, and actress born in Vienna. Educated by renowned teachers, she began performing as a concert pianist at the age of six and debuted on stage as an actress at 13 in 1848. As a composer, Geiger first gained attention at the age of nine with her Preghiera for military music, performed on 20 April 1845, in a Vienna parish church. While the audience reacted positively, specialist magazines gave it a mostly negative review, partly due to her youth and gender. Additionally, her choice to compose military music, a genre considered inappropriate for women at the time, further attracted criticism.

Constanze Geiger

Geiger performed as a pianist, and her compositions were deemed “crafted and virtuosic.” Her compositions, however, were often criticised by the press, with some describing them as more suitable for intimate, familial settings than for a sophisticated, art-educated audience. Despite this, her works were regularly performed in Vienna and published by well-known music publishers, indicating that they had an audience and were valued within certain circles, even if not universally acclaimed.

She joined Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in a morganatic marriage in 1862 and withdrew from public concert and theatre life. Her compositions, however, continued to be performed. The couple had a close friendship with the Strauss family, and Johann Strauss (father) dedicated his “Flora Quadrille” to Geiger. Her waltzes and marches were performed by countless military bands and orchestra under the direction of both Strauss father and son.

Josefine Weinlich

Josefine Weinlich: Freie Gedanken (Free Thoughts)

Josephine Weinlich (1848-1887) was a pianist, violinist, composer, and conductor from Dechtitz (now Dechtice, Slovakia). She was the daughter of Franz Weinlich, a ribbon manufacturer who lost his fortune during the 1848 revolution and who turned to managing a folk singer company. All his daughters were licensed to perform. He probably taught Josefine to play the piano and violin, and she might have received occasional lessons from Clara Schumann as well.

In 1867, Franz Weinlich founded a pioneering all-female instrumental quartet in Vienna, marking a significant departure from 19th-century gender norms that restricted women in music. The quartet initially performed in private settings, with Josephine actively managing and promoting the ensemble. The quartet’s creation was a bold statement in a time when female musicians had limited opportunities, especially in public or professional performances.

Josephine Weinlich

Josephine was acting as the capellmeister, and over time, the ensemble expanded and performed at various larger Viennese venues, often in varying line-ups of six to eight musicians. The orchestra’s activities were documented in the press, and there are records of continuous efforts to recruit new members throughout the years. This ensemble challenged the conventions of the time, especially the notion that women could not lead or participate in formal musical ensembles in Vienna’s prominent public music scene. It’s rather similar to La Philharmonica’s efforts in 2025—how little things have changed!

Leopoldine Blahetka

Leopoldine Blahetka

Leopoldine Blahetka: Introduction and Variation, Op. 39 (Noémi Győri, flute; Suzana Bartal, piano)

Leopoldine Blahetka (1809–1885) was a pianist, harmonica player, piano teacher, and composer born near Vienna. Her father, was a music writer, mathematician, and history teacher, and a friend of Beethoven. Her mother, Barbara Sophia (Babette) Blahetka, was a skilled glass harmonica player and the niece of the Viennese music publisher Johann Baptist Traeg. Leopoldine received her first music education from her mother, then studied piano with various notable teachers, including Joachim Hoffmann, Joseph Czerny, Katharina Cibbini, and briefly with Friedrich Kalkbrenner and Ignaz Moscheles.

Leopoldine Blahetka was only eight years old when she made her public debut on 1 March 1818. In the same year, the composer Joseph Doppler wrote to Franz Schubert on behalf of her father. Her father’s request was for Schubert to compose a “Rondo brilliant” for Leopoldine to perform at an academy, specifically for piano with orchestral accompaniment. The father emphasised that Schubert could make the piece as technically challenging as desired, but it should avoid overly difficult hand stretches. Sadly, Schubert did not fulfill this request.

Blahetka performed Beethoven’s Op. 19 at the age of 11 and she embarked on a number of concert tours before settling in Vienna. She performed regularly in Vienna, taught music, and maintained connections with prominent musicians like Beethoven, Schubert, and Chopin. She also participated in a charity concert organised by Niccolò Paganini on 16 May 1828. The grumpy music critic Eduard Hanslick later described her as one of the few “child prodigies” who continued to delight audiences into adulthood. He praised her as a graceful pianist, noting that her annual concerts were well-received, and she often performed Beethoven’s works with great success.

Mathilde Kralik

Mathilde Kralik

Mathilde Karlik (1857-1944) was the daughter of a Bohemian glass industrialist. Her family was highly musical, with her father playing the violin and her mother the piano. Her talents were recognised early, and she studied with such greats as Anton Bruckner, Franz Krenn, and Julius Epstein. She entered the Conservatory of the Society of Friends of Music from 1876 to 1878, winning awards for her compositions, including second prize for a “Scherzo” and first prize for her graduation project, an “Intermezzo.”

Kralik didn’t need to rely on her music for financial support due to her family’s wealth, which allowed her to live a more private life within the upper society. Music remained her passion, and she composed as a hobby while maintaining an active social life, particularly within musical and cultural circles. Kralik often performed in public but typically sought out her own audiences, hosting regular Sunday morning matinees at her elegant apartment in Vienna. These gatherings earned her a reputation as a respected composer.

Mathilde Kralik was a prolific composer, crafting more than 260 works, mostly vocal music, including operas, oratorios, choral pieces, and songs with piano. She often collaborated with her brother, Richard Kralik, as her preferred lyricist. Her personal life was marked by a close, private relationship with Dr. Alice Scarlates, who inherited her compositional estate. This ensured the preservation of Kralik’s works, which remain accessible for performance today.

As Michael Wittmann writes, “Kralik’s music remains an important part of Austrian cultural history, reflecting a blend of late Romanticism and early modernism with a personal and intimate character.” Two other women composers feature in the La Philharmonica concert, Gisela Frankl and Anna Gräfin von Stubenberg. Sadly, I could not find any available recordings. As Irene Suchy once stated, “Music has overlooked half of the music creators, women. Women need to be more visible.” It’s great that this fresh take on the New Year’s Concert redresses this horrible imbalance.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Mathilde Kralik: Nonet (Ursula Kepser, horn; Gerda Sperlich, horn; Christopher Corbett, clarinet; Relja Kalapiš, bassoon; Korbinian Altenberger, violin; Alexander Kisch, violin; Benedikt Schneider, viola; Samuel Lutzker, cello; Oliver Triendl, piano)