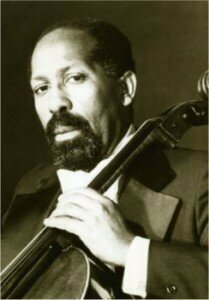

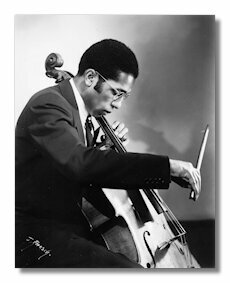

Kermit Moore

Although African-Americans have excelled in jazz, gospel, R & B, hip-hop and other genres of music, the many influential artists, composers, and performers of classical music in the twentieth century are relatively unknown. They include the cellist Kermit Moore who distinguished himself as a teacher, composer, conductor, and soloist.

He was born in Akron, Ohio in 1929, was already studying piano with his mother at age five, and at age ten, Kermit began to study the cello. A job as an usher at the Armory of Akron, a large concert hall, changed his life. When the Boston Symphony performed there, the sensuous sound of the orchestra under Koussevitzky seemed magical to the fourteen-year-old. Although he had heard the Cleveland Orchestra with George Szell, this concert mesmerized Moore and he vowed to try to reproduce the shimmering sounds on his cello.

Moore began to study at the Cleveland Institute of Music when he was in high school, and

in 1947, when he was eighteen, Kermit Moore received a scholarship to attend Tanglewood— the summer home of the Boston Symphony. He was able to study there with Gregor Piatigorsky, and William Primrose, as well as lead the student orchestra’s cello section under Koussevitzky himself. That year he was accepted at the Juilliard school, to study with the outstanding pedagogue and cellist Felix Salmond—the teacher of Leonard Rose and Samuel Mayes. Moore was his only black pupil.

It didn’t take long for Moore to make his recital debut in New York’s Town Hall. Salmond loaned Moore his valuable Italian Matteo Goffriller cello for the occasion, and the concert was so impressive. Peter G. Davis, critic of The New York Times, wrote: “Mr. Moore vaulted every technical hurdle of his formidable recital with disarming ease, and he instinctively found a precise stylistic voice for each composer. He is a virtuoso cellist, a sensitive musician and something of a hero.”

Karl Weigl: Cello Sonata in G Major – I. Allegro con fuoco (Kermit Moore, cello; Richard Woitach, piano)

In the meantime, Piatigorsky became an advocate. Moore urgently needed a good cello. After a letter was published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer indicating Piatigorsky’s involvement, a Tononi cello was found for Moore. In 1948, six-thousand dollars was a lot of money. Moore’s father was flabbergasted since Kermit’s previous cello had only cost $500, but the investment paid off.

While Moore studied cello at Juilliard, he concurrently studied composition and musicology at New York University, where he earned his master’s degree. By the time he was 20 years old, in 1949, Kermit became principal cello of the Hartford Symphony Orchestra—one of only a few African Americans in a U.S. orchestra, especially in those days. He began his teaching career at the University of Hartford, Connecticut.

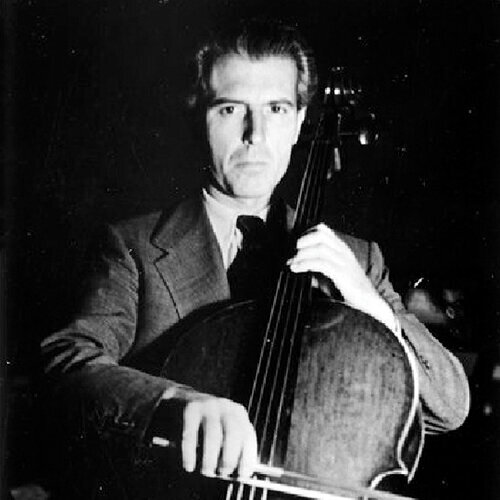

Moore decided to further his studies and went abroad. He worked with Paul Bazelaire, (who had been the teacher of Pierre Fournier) at the Paris Conservatoire, and in 1963, he and his wife Dorothy studied with the renowned teacher Nadia Boulanger at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau. They were in good company. A number of the leading composers and musicians of the 20th century worked with Boulanger including—Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, Elliot Carter, and Leonard Bernstein; African-American composers Robert George Walker, Quincy Jones, Julia Perry, as well as Astor Piazzolla, Phillip Glass, and Daniel Barenboim.

Moore decided to further his studies and went abroad. He worked with Paul Bazelaire, (who had been the teacher of Pierre Fournier) at the Paris Conservatoire, and in 1963, he and his wife Dorothy studied with the renowned teacher Nadia Boulanger at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau. They were in good company. A number of the leading composers and musicians of the 20th century worked with Boulanger including—Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, Elliot Carter, and Leonard Bernstein; African-American composers Robert George Walker, Quincy Jones, Julia Perry, as well as Astor Piazzolla, Phillip Glass, and Daniel Barenboim.

Kermit Moore performed as soloist with some of the leading orchestras in the world including the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, the Concertgebouw, and the National Radio Symphony of France, and he had a remarkable career as a conductor. In an interview with Victor Koshkin-Youritzin, in Classical Net, Moore indicated how indebted he was to both Koussevitzky and Herbert von Karajan for his own conducting proficiency. Koussevitzky would tell him, “nothing is more important than the upbeat.” Later, in a master class in Milan, Karajan reinforced this idea, shouting, “You’re not singing. You must be singing long before you give your upbeat.” Moore said both maestros’ success was due to anticipating the opening of a piece, with a clear preparatory beat, and to follow with a decisive gesture. “I have played under Stokowski, Szell, Bernstein, and a lot of other people—Franz André in Belgium, and von Knappertsbusch… So many works require a very clear, cogent downbeat, and Koussevitzky had that better than anybody I’ve ever seen.”

Dorothy Rudd Moore

From the above-mentioned interview, I learned Kermit Moore had a simple yet important goal—“Make the most beautiful possible sound. Don’t make ugly sounds unless the composer asks for them.” He urged his students not to press, squeeze, or choke their instrument. “You can’t sing if you’re pressing. It becomes a hard, unyielding sound.”

Kermit Moore and his wife Dorothy Rudd Moore were founding members of the Society of Black Composers, and the Symphony of the New World (1964-1976). They championed African-American artists, featuring both composers and performers. Kermit also led a chamber orchestra—the Classical Heritage Ensemble. Several composers wrote for him including Margaret Bonds who was the first black soloist to appear with the Chicago Symphony, in 1933.

Moore was a prolific composer himself, of works for cello, for chamber music, for film, and he collaborated with musicians of many genres. Moore’s music can be heard in the 1984 film Solomon Northup’s Odyssey—the same protagonist as the recent movie 12 Years a Slave. His compositions include a flute sonata, Music for Cello and Piano, a concerto 2006, De Natura Naturae – for ten instruments, five woodwinds and five strings, a Timpani Concerto, Music of Nature and the Gods for clarinet, cello and piano, and Tetelestai for baritone, clarinet, cello and piano. His Music for Viola, Piano and Percussion, was performed and recorded by Emanuel Vardi, and premiered in New York’s Alice Tully Hall in 1983.

Moore also commissioned his wife to write for him. Premiered in Richmond, Virginia, during one of Moore’s cello recitals, From the Dark Tower—a song-cycle with librettos by African-American poets, for mezzo-soprano, cello and piano, was also performed with the Symphony of the New World, at Avery Fisher Hall, and with the Birmingham, Alabama Symphony.

His programs were eclectic. He mixed standards of the repertoire with contemporary works. The opening program for the African American Classical Music Series, in Alexandria, Virginia, which took place at the George Washington Masonic National Memorial in 2001, included Vivaldi’s Sonata No. 5, Schumann’s Fantasy Pieces Op. 73, Duke Ellington, Clarence Cameron White, Brahms Sonata in E minor, Op. 38, a solo cello piece by Dorothy Rudd Moore, and Moore’s own Caravaggio Revisited.

Dorothy Rudd Moore – From the Dark Tower – single song from cycle, Kermit Moore cello

Moore was a faculty member of the Chamber Music Conference and Composers’ Forum of the East in Bennington, Vermont for 21 years. He died in 2013 at the age of 84. The interview with Moore below shows a man full of passion for music.

An Interview with Kermit Moore

By Victor Koshkin-Youritzin

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

The article is wonderful but the title does not apply. Kermit Moore is my uncle. I shall never forget him. Thanks for this accounting of his impact.

Margaretta of course you won’t! But those of us who weren’t fortunate enough to meet him in person may not have known about his major accomplishments. Thanks for writing.

With my best wishes

Janet

Margaretta of course you won’t! But those of us who weren’t fortunate enough to meet him in person may not have known about his major accomplishments. Thanks for writing.

Hello ,

Thanks for writing. It’s wonderful to hear more about this artist from those who crossed paths with him.

Janet

Margretta Williams,

Hello. I regret the delay of my response to your comment here, and I concur with it. I gave remarks at Kermit’s memorial service at St. Peter’s/CITICORP in January 2014. Have you heard any updates about Dorothy? Timothy Holley (cellist, NCCU)

Hi, Timothy Holley. Thanks for your note. I am glad you were able to give some insight at his memorial service. At the time I was unable to attend, due to health issues. I am well now. Feel free to friend me on Facebook (Gretta Williams). My email is [email protected]

When I hear from you I will share what I know now about my Aunt Dorothy. Please take care. –Gretta

I was a student of Kermit for nearly 7 years. I, too, think of him often. He was one of the best musician, teacher, humorists, and person that I have ever known. My time spent with Kermit was a true blessing. Thanks for the article.

Hello and thanks for writing. It’s wonderful to hear more about this artists from those who crossed paths with him.

Janet

Janet Horvath Congratulations on a wonderful ‘birds eye view’ of my uncle, a renowned and committed artist and extraordinary human being. We are preparing to celebrate the life of his sister, Mary Moore, who was an extraordinary musician and composer in her own right. She often accompanied our uncle upon his return from an extended stay in Europe. We will give her rites this Saturday, December 10th. My uncle opened the doors of the classical music world for today’s gifted musicians, including Yo Yo Ma. It is because of Kermit D. Moore, who loved life and music, that he dedicated his activism to help musicians , vocalists, composers, conductors ….these young African Americans who dare to carve a significant path for others to follow. Thank you for recognizing the value of the late Kermit D. Moore. I am certain Julliard, Tanglewood, and the total music word miss him. His, Dorothy Rudd Moore passed this spring (2022) and together she with her piano mastery, composing, and vocal accomplishments increased the value of African American musicians. Lovely article. May they both rest in power and continue to encourage musicians everywhere! nj

Hello Netosh, Thank you so much for your comments. What a talented family and I am pleased to be introduced to them. Our condolences to your family upon the passing of Mary Moore and Dorothy Moore.Kermit was indeed a trailblazer and we are all fortunate for his wonderful contributions to African American artists and the entire music world at large!

All best

Janet