Isolated from the surrounding carnage of WWI, Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) began to synthesise elements of German Romanticism and Eastern Exoticism through an exploration of Greek mythical subject matters and concepts from the French fin de siècle of Debussy and Ravel.

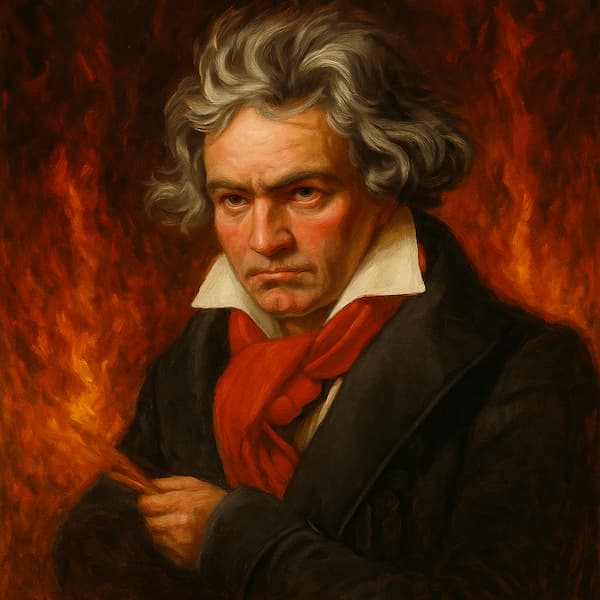

Karol Szymanowski

Szymanowski, accompanied by his cousin and poet Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, made an earlier trip to Africa and Sicily in 1914. Having felt like an outsider throughout much of his youth, he now matured as a man and musician. “This outsider mentality became connected to his identity as a Polish composer and his homosexuality, which he had come to realise and accept on this particular trip.”

Myths

While a good many contemporary composers in Poland focused on national sentiment, Szymanowski, alongside Polish poets and writers, explored the subject of mythology and eroticism. A scholar writes, “In Myths, Szymanowski successfully channels his inner world, a personal aesthetic concept embodying imagination and detachment, through the use of exotic imagery, mythical narrative, and the attendant musical devices.”

Karol Szymanowski: Myths, Op. 30 “The Fountain of Arethusa”

Szymanowski completed his three violin and piano poems Myths in the same year as his piano works Metopes, Op. 29 and Masques, Op. 34. All three works depict impressions from his travels in Sicily and draw from specific tales from Greek mythology. As an editor wrote, “these tone poems reflect the repercussions of Szymanowski’s journey to Italy and Sicily in 1911 and 1914, but these are remote repercussions—they are more a musical meditation on classical mythological threads than a transposition of direct impressions or an exact literary programme.”

The Fountain of Arethusa

Alpheus and Arethusa

“The Fountain of Arethusa,” the first of the Mythes, has become one of Szymanowski’s most popular pieces. The myth tells how Arethusa, one of the Hesperides, is pursued by the hunter Alpheius. Attempting to protect her virginity, she takes refuge on the Isle of Ortygia, where she is turned into a spring, while Alpheius changes into a river on Mount Olympus. The river (Alpheius) then crosses the sea without mingling with its waters and joins the spring (Arethusa) on Ortygia.

The entire movement seemingly derives from the opening material offered in both the piano and violin parts, and subsequent melodies are variations of this opening line “either by addition of subsidiary motives, inversions or elisions.” Szymanowski creates a bitonal framework of stability, with each instrument representing one of the tonal centres. These two tonal centres from the interval of a tritone, and there exists a delicate balance between the colouristic qualities of the harmonies and their functions in outlining temporary tonalities. And let’s not forget that the evocation of water in its many moods goes beyond the colouristic but assumes structural importance.

Karol Szymanowski: Myths, Op. 30 “Narcissus”

Narcissus

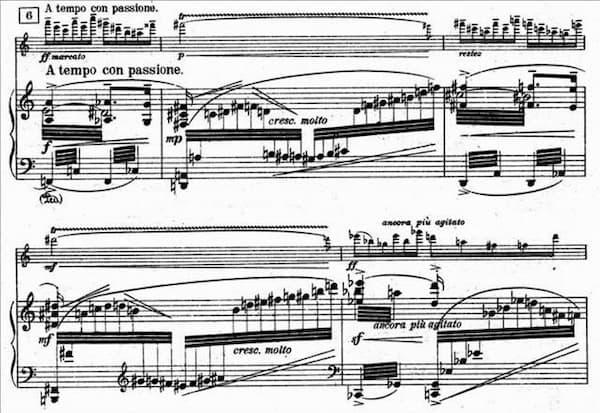

Karol Szymanowski’s Myths music score excerpt

In the second movement of Myths, Szymanowski invokes the well-known story of Narcissus, son of the river god Cephissus and a hunter known for his immense beauty and vanity. Lured to a pool of water by the goddess Nemesis, he sees his reflection and falls in love with his image. His beauty enthralled him so much that he could not look away, and as a punishment from the gods, there he remained transfixed until his death. The story concludes with a beautiful flower growing upon the spot where Narcissus perished.

The piece opens with a melody and accompaniment texture, with the tritone and the interval of a perfect fourth forming an important layer. This is set against a dominant-quality trichord, and the grace notes and bass pedals. “Szymanowski exploits the tonal tensions between these units to create a single resonating dissonance rather than an effect of bitonality. Each instrument depicts the presence of the two integral elements: reflective water in the piano and the character and beauty of Narcissus in the violin.

Dryads and Pan

The Dryads © charlois.com

The final movement, “Dryads and Pan,” depicts a forest scene replete with inebriated nymphs dancing amidst the humming and murmuring of the evening in “an evocation of the forest murmurs of antiquity.” The amorous god Pan, shepherd of the woods and pastures, appears with his pipes. Pan, traditionally described as having the legs and horns of a goat, incites fright and panic when he appears, and an expected moment of fright and a subsequent flurry ensues in this myth.

This tone poem also has a tonal focus, almost immediately suggested at the beginning. This particular centre returns at important structural points. Szymanowski creates a rich harmonic environment, including jarring dissonances. The programme of “Dryads and Pan” seems even more clearly expressed, and that includes the murmurs of the forest, the trills of Pan’s flute, and, of course, the essence of the dance as a creative force. Myths is considered an important milestone in 20th-century violin writing and was greatly admired by Béla Bartók and Sergei Prokofiev.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter