“Mathematical formulas translated into beautiful and convincing music”

Iannis Xenakis

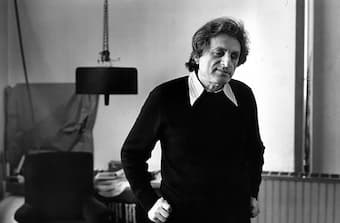

In 2022 we celebrate the centenary of the birth of Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001), an artist of fierce originality who produced some of rawest and wildest music in history. He belonged to a pioneering generation of composers who revolutionized 20th-century music after World War II. “With the ardour of an outsider to academic musical life, he was one of the first to replace traditional musical thinking with radical new concepts of sound composition… However, his musical language remained singular for its uncompromising harshness and conceptual rigour.”

Born in Romania, his family moved to the Greek island of Spetses, and Iannis immersed himself in science and Greek literature. While preparing for the civil engineering entrance examination to the Athens Polytechnic, Xenakis also took lessons in piano and music theory. The Polytechnic closed in 1940 following the Italian invasion of Greece. During World War II, Xenakis fought in Greece with the communist-led National Liberation Front, opposing British efforts to restore the monarchy after the war. He was severely wounded in December 1944, and condemned to death for his political activities. His Greek citizenship was revoked, but Xenakis managed to get into Italy on a fake passport and illegally crossed into France thereafter.

Born in Romania, his family moved to the Greek island of Spetses, and Iannis immersed himself in science and Greek literature. While preparing for the civil engineering entrance examination to the Athens Polytechnic, Xenakis also took lessons in piano and music theory. The Polytechnic closed in 1940 following the Italian invasion of Greece. During World War II, Xenakis fought in Greece with the communist-led National Liberation Front, opposing British efforts to restore the monarchy after the war. He was severely wounded in December 1944, and condemned to death for his political activities. His Greek citizenship was revoked, but Xenakis managed to get into Italy on a fake passport and illegally crossed into France thereafter.

Iannis Xenakis: Pithoprakta

Philips Pavilion

Xenakis would make Paris his permanent home, and he managed to secure a job with the studio of Le Corbusier. He first worked as an engineer, but soon started to take a bigger role in architectural design. “His love of curving forms and irregular pattern had a perceptible effect on two major Le Corbusier structures; the monastery at Sainte-Marie de la Tourette, with its undulating glass façade, and the Philips Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair.” Both architectural projects were intended for musical uses, and Xenakis became interested in Le Corbusier’s system of numeral proportions, concepts that Xenakis would start to incorporate into his musical compositions. Lacking formal musical training, Xenakis approached Nadia Boulanger and Arthur Honegger for lessons, but he was quickly dismissed. Lessons with Darius Milhaud seemed to go nowhere, and on the advice of a friend, Xenakis approached Olivier Messiaen. Messiaen later recalled, “I understood straight away that he was not someone like the others… He is of superior intelligence… I did something horrible, which I should do with no other student, for I think one should study harmony and counterpoint. But this was a man so much out of the ordinary that I said… No, you are almost thirty; you have the good fortune of being Greek, of being an architect and having studied special mathematics. Take advantage of these things. Do them in your music.”

Iannis Xenakis: La Déesse Athena

Iannis Xenakis: Metastaseis

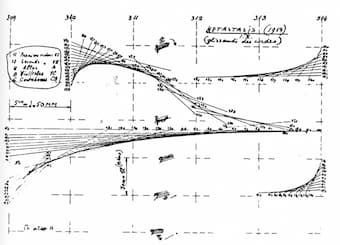

With his engineering and architectural interest in sound masses and shapes, “it is not surprising that Xenakis’ first compositions were for orchestra.” Xenakis described the foundation of his concept of sound composition in an essay entitled “Les Métastassis.” He writes, “The sonorities of the orchestra are building materials, like brick, stone and wood… The subtle structures of orchestral sound masses represent a reality that promises much.” Generally regarded as the composer’s first mature piece, Metastaseis, which the composer translates as “transformations,” was composed during 1953 and 1954 and first performed at the 1955 Donaueschingen Festival. It refers to the continuous evolution of massive glissando structures, “and the discontinuous transpositions and permutations of pitches on the other.” This concept of transformation, “in a strictly mathematical sense the interrelations between musical structures, is central to Xenakis’ thought. During the process of composition, Xenakis sketched the string glissandos in an architectural graph, with pitch on the y-axis and time on the x-axis. It reflects Xenakis’ “basic concept of musical space-time, as a two-dimensional space is created in which potentially time-independent musical structures can be contained in a temporal setting.”

Iannis Xenakis: Metastaseis

Xenakis left the studio of Le Corbusier in 1959 and made his living composing and teaching. In addition, he quickly became recognized as one of the most important European composers of his time, “and he became almost a pop classic on New York’s new-music scene.” He was a pioneer in the field of computer-assisted composition, and he wrote a number of seminal articles and essays on music. As an atheist, Xenakis emphasized the finality of death as the ultimate event of human life. He wrote, “Man is one, indivisible, and total. He thinks with his belly and feels with his mind. I would like to propose what, to my mind, covers the ‘term’ music… It is a mystical but atheist asceticism.” Xenakis continued to make music in more intimate chamber structures, “his choices as unpredictable as the motions of his beloved particles… He found new ways of translating images into sound, and his final works tend toward extreme density.” His music is often extremely elaborate in detail, but “form never emerges from the development of thematic cells but from the collage-like succession or superimposition of segments that display strong internal connections.” After several years of serious illness, the composer “who sought a total exaltation in which the individual mingles, losing his consciousness in a truth immediate, rare, enormous, and perfect,” died in Paris on 4 February 2001.

Xenakis left the studio of Le Corbusier in 1959 and made his living composing and teaching. In addition, he quickly became recognized as one of the most important European composers of his time, “and he became almost a pop classic on New York’s new-music scene.” He was a pioneer in the field of computer-assisted composition, and he wrote a number of seminal articles and essays on music. As an atheist, Xenakis emphasized the finality of death as the ultimate event of human life. He wrote, “Man is one, indivisible, and total. He thinks with his belly and feels with his mind. I would like to propose what, to my mind, covers the ‘term’ music… It is a mystical but atheist asceticism.” Xenakis continued to make music in more intimate chamber structures, “his choices as unpredictable as the motions of his beloved particles… He found new ways of translating images into sound, and his final works tend toward extreme density.” His music is often extremely elaborate in detail, but “form never emerges from the development of thematic cells but from the collage-like succession or superimposition of segments that display strong internal connections.” After several years of serious illness, the composer “who sought a total exaltation in which the individual mingles, losing his consciousness in a truth immediate, rare, enormous, and perfect,” died in Paris on 4 February 2001.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Iannis Xenakis: O-mega