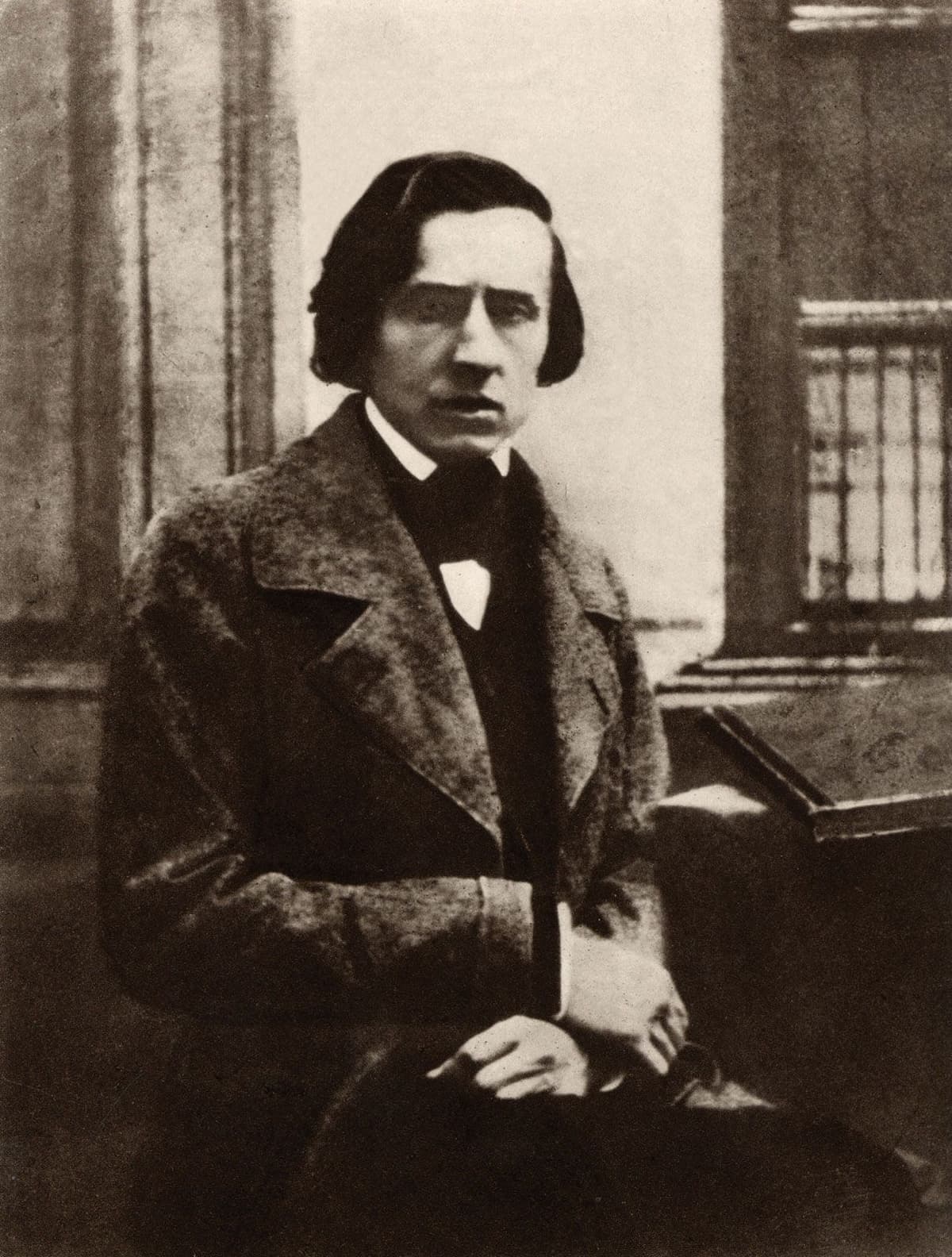

Even people with no interest in classical music instantly recognized the famous “Minute Waltz” Op. 61, No. 1 by Frédéric Chopin. My mother, who never had any musical training, happily hums along as soon as she hears the first couple of notes. Chopin originally called it the “waltz of the puppy,” as he was watching a small dog chasing its tail. The unofficial nickname “Minute Waltz” actually comes from a publisher, who simply described it as a musical miniature. The pianist comedian Victor Borge joked that the “Minute Waltz” got its name because of the composer’s preference for perfectly soft-boiled eggs. Since his housekeeper couldn’t time it correctly, Chopin played the waltz tree time and the eggs would be perfect. With the waltz taking closer to two minutes to play, Chopin’s eggs must still have been dreadful!

Frédéric Chopin

It’s a really funny story, and it certainly underscores the worldwide popularity of this little gem. The popularity of this charming but rather unpretentious little piece of music is further detailed by a spectacular number of ingenious and funny transcriptions, and we will sample some in this blog.

Marc-André Hamelin: “The Minute Waltz, in Seconds”

Marc-André Hamelin

One such transcription, which I had previously shared with you already, comes from the hands of pianist Marc-André Hamelin. His rendition opens with the original strains of the Chopin waltz. But things get really interesting when Hamelin then proceeds to perform the melodic line in “Seconds,” not in terms of playing the music faster, but by incorporating the musical intervals of major and minor seconds into the score.

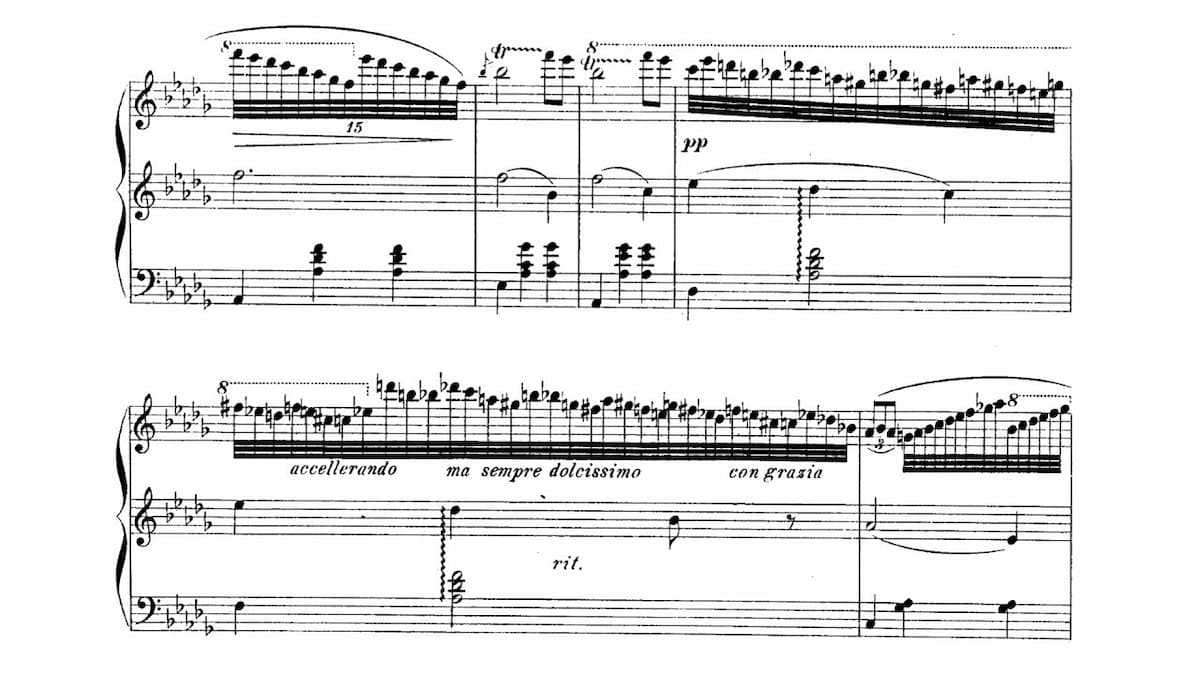

Isidor Philipp: First Concert Study after a Waltz by F. Chopin

Isidor Philipp: First Concert Study after a Waltz by F. Chopin (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

Isidor Philipp: First Concert Study after a Waltz by F. Chopin

We are very fortunate that BIS Records has recently released an entire disk devoted to various re-workings of pieces by Chopin, with the “Minute Waltz” taking center stage. What an invaluable sound resource to have at our disposal, and we are delighted to share some of these exciting transcriptions of Chopin’s “Minute Waltz” with our readers. So, let’s get started with the French pianist teacher, and composer of Hungarian origin, Isidor Philipp (1863-1958). He was a student of Stephen Heller and Camille Saint-Saëns, and later a professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire from 1893 to 1934. According to scholars, “Philipp had a legendary ability to solve pianist problems, and he published 13 collections of piano exercises and studies.” Chopin’s “Minute Waltz” provided Philipp with a springboard for a light-hearted transcription that placed the theme in the left hand, with the right hand freed to present a mazurka-like theme as a surprising countersubject.

Isidor Philipp: Concert Study for the Left Hand after Chopin

Isidor Philipp: Concert Study for the Left Hand after Chopin (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

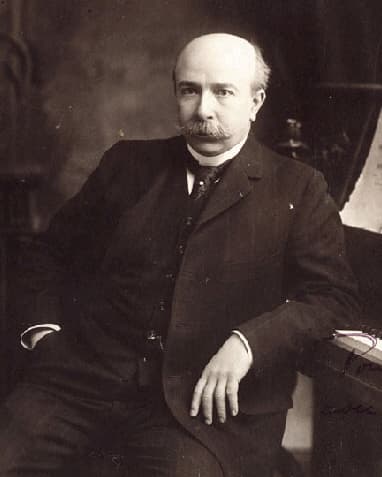

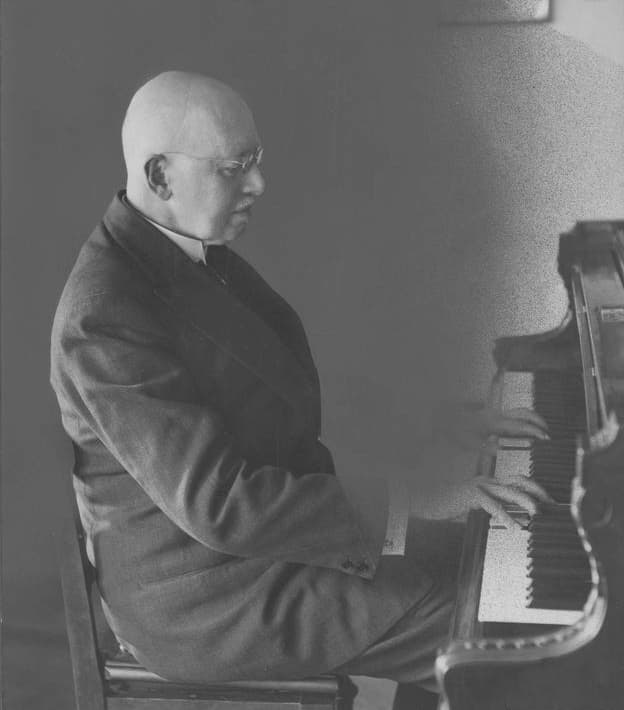

Isidor Philipp

Isidor Philipp made his home in the United States after the outbreak of World War II, and like many of his colleagues, he was aware of the heroic efforts of pianist Paul Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein had been a prominent Viennese pianist, but he was wounded during WWI and his right arm had to be amputated. Wittgenstein was determined to continue his career as a left-hand virtuoso and he created his personal repertory. For one, he fashioned hundred of arrangements of piano works and operatic arias, and he commissioned an impressive chamber and concerto repertory. I think we all know the Ravel Concerto for the Left Hand written specifically for Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein certainly inspired pianists and composers around the globe, and Isidor Philipp fashioned a transcription of the “Minute Waltz” for piano left hand. The theme is placed in the center of the keyboard, and the left hand simultaneously plays the theme, provides the bass support, and sounds the theme surrounded by brilliant passages and musical garlands. How impressive is that!

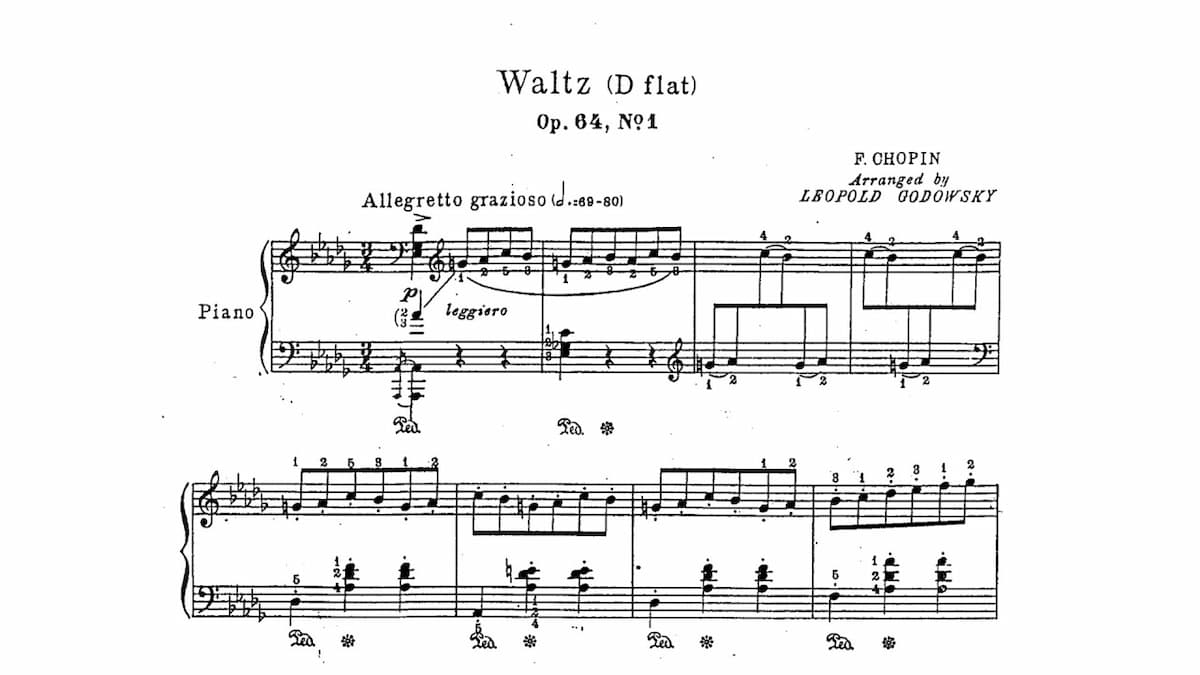

Leopold Godowsky: Chopin Waltz in D-flat Major, Op. 64, No. 1 (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

Leopold Godowsky: Chopin Waltz in D-flat Major, Op. 64, No. 1

Leopold Godowsky: Chopin Waltz in D-flat Major, Op. 64, No. 1

The Polish pianist Leopold Godowsky (1870-1938) had one of the most perfect pianistic mechanisms of all times. It’s almost inconceivable, but Godowsky only received three months of instruction at the Berlin Hochschule; his piano technique and musical understanding were self-made as he was an autodidact genius. Godowsky once wrote, “I love the piano and those who love the piano. The piano as a medium for expression is a whole world by itself. No other instrument can fill or replace its own say in the world of emotion, sentiment, poetry, imagery, and fancy.” To be sure, Godowsky had a fabulous gift for transcription as we can easily hear in his 53 studies on the Chopin Etudes. Godowsky, according to a scholar, “was the only composer to have added anything of significance to keyboard writing since Liszt.” And we can hear the dense contrapuntal textures of Godowsky’s music in his little take on the “Minute Waltz.” It is a nostalgic and mildly ironical retrospect, “with subtle harmonic modifications and embellishments.”

Rafael Joseffy: Concert Study on the Chopin Waltz Op. 64, No. 1

Rafael Joseffy: Concert Study on the Chopin Waltz Op. 64, No. 1 (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

Rafael Joseffy

Rafael Joseffy (1852-1915) received his piano lessons from Ignaz Moscheles, Carl Tausig, and Franz Liszt. Acclaimed “a master pianist of great brilliance,” he was also one of the most poetic of all pianists. Joseffy immigrated to the United States and made numerous concert appearances, yet he was also a painfully private man. Eventually, concert life did not agree with his nervous disposition, and he devoted himself to teaching, editing, and publishing. He also composed a number of popular piano compositions and edited the works of Chopin for G. Schirmer music publishers.

His most important legacy to the pianistic world is his “School of Advanced Piano Playing,” and a number of highly musical yet incredibly difficult Chopin arrangements. And that includes a humorous and capricious concert study on the “Minute Waltz.”

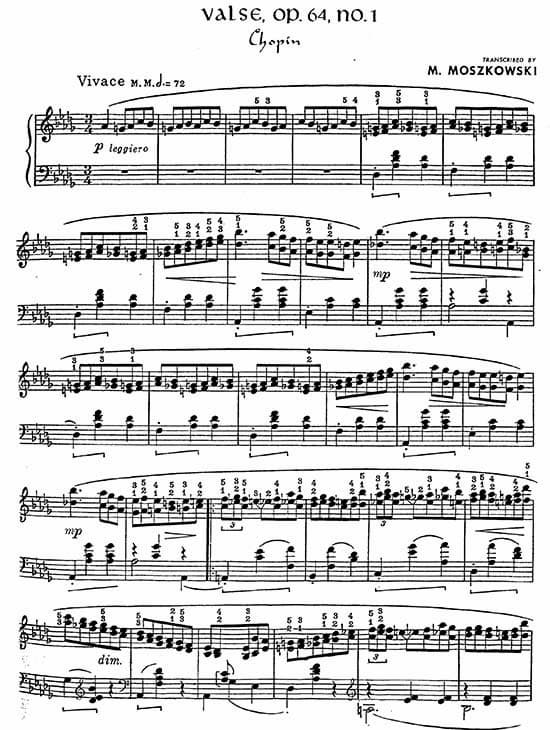

Moritz Moszkowski: Waltz, Op. 64, No. 1 (Chopin)

Moritz Moszkowski: Waltz, Op. 64, No. 1 (Chopin) (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

Moritz Moszkowski: Waltz, Op. 64, No. 1 (Chopin)

The fabled pianist Ignacy Paderewski said, “After Chopin, Moritz Moszkowski best understands how to write for the piano, and his writing embraces the whole gamut of piano technique.” Moritz Moszkowski was born in 1854 and showed exceptional talent from an early age. At the age of 17 he joined the faculty at the “New Academy of Music” in Berlin, and he quickly gained a reputation as a brilliant virtuoso. However, he was also considered one of the finest interpreters of the Classical and Romantic repertory, and his compositions included a piano concerto that was much admired by Liszt. He made his reputation with his piano music, which ranges from brilliant virtuoso pieces suited to both the concert and recital halls to lighter salon music. And fittingly, he fashioned a number of Chopin arrangements characterized by glittering brilliance, innocent charm, and immediate melodic appeal. In his “Minute Waltz” transcription, the outer sections are scored in thirds while the theme in the middle section is accompanied by graceful triplet figuration.

Moriz Rosenthal: Study on the Waltz, Op. 64, No. 1 by Chopin

Moriz Rosenthal: Study on the Waltz, Op. 64, No. 1 by Chopin (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

Moriz Rosenthal

Moriz Rosenthal (1862-1946) ranked among the finest pianists of his time, combining a prodigious technique with a profound sensitivity for phrasing, rubato, and tone-colour. Born in L’viv, Rosenthal received his first lessons from Karol Mikuli, Chopin’s assistant, and by 1875 he moved to Vienna to study with Rafael Joseffy. Rosenthal met Franz Liszt in 1877, and over a nine-year period received private lessons in Rome and Weimar from the legend. Rosenthal was legendary for his malicious wit, his sharp tongue, and his bright intellect. When he heard Horowitz blaze through the octave passages of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto at his Vienna debut, he remarked: “He is an Octavian, but not Caesar.” And when a colleague once played his arrangement of Chopin’s “Minute Waltz” in thirds at a recital, Rosenthal thanked the pianist “for the most enjoyable quarter of an hour of my life.” Similar to the transcription of Moszkowski, Rosenthal’s version is essentially an etude in thirds with “some very clever contrapuntal tricks in the middle part.”

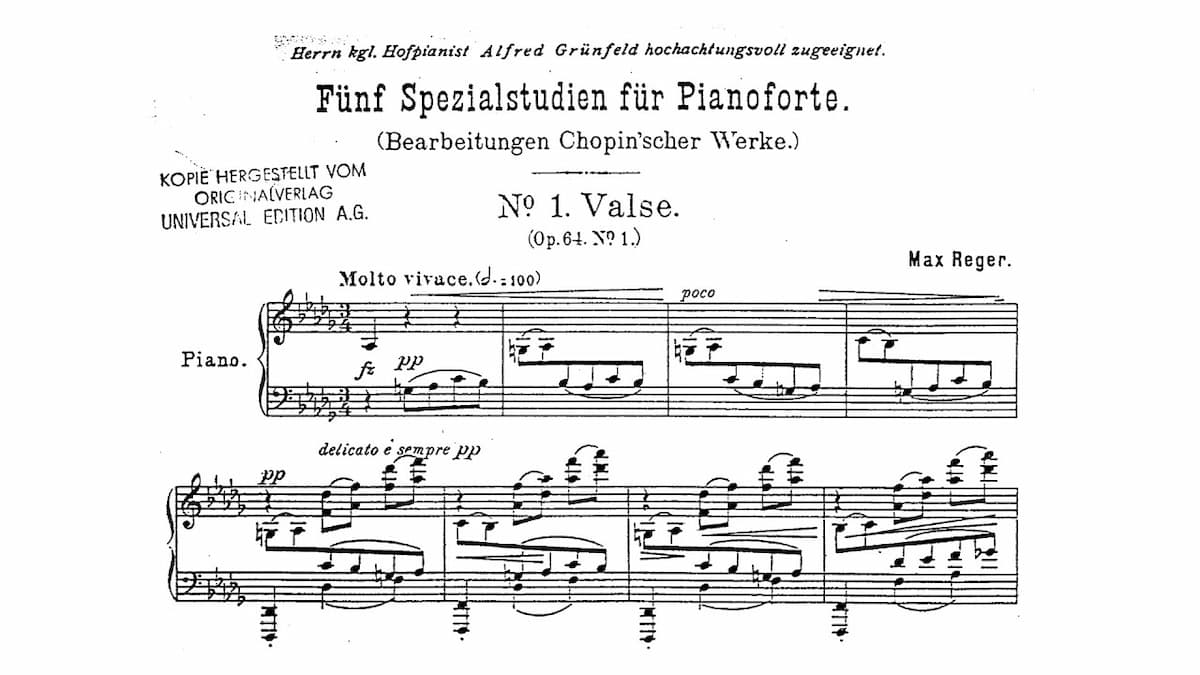

Max Reger: Five Special Studies for Piano, No. 1 “Waltz in D-flat Major”

Max Reger: Five Special Studies for Piano, No. 1 “Waltz in D-flat Major” (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

Max Reger: Five Special Studies for Piano, No. 1 “Waltz in D-flat Major”

Max Reger (1873-1916) had a distinct musical voice that is based on narrative spontaneity and cast in traditional genres. His music was always a bit controversial, but always highly original and immediately recognizable. His music remains strictly tonal, but his advanced harmonic language and extremely fast modulations make his music sound very modern. In 1899, Reger produced a collection of 5 Special Studies based on works by Frédéric Chopin. Each study is dedicated to a famous pianist, and the transcriptions are fiendishly difficult. The “Minute Waltz” becomes part of a dense and luxuriant soundscape generated via a highly sophisticated polyphony. Contrapuntal textures weave together different melodic strands, and even though it is almost impossible to play in a technical sense, it completely forgoes pianistic showmanship. Essentially we are listening to a double thirds etude played in double-sixths.

Giuseppe Ferrata: Study on Chopin’s Waltz, Op. 64, No. 1

Giuseppe Ferrata: Study on Chopin’s Waltz, Op. 64, No. 1 (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

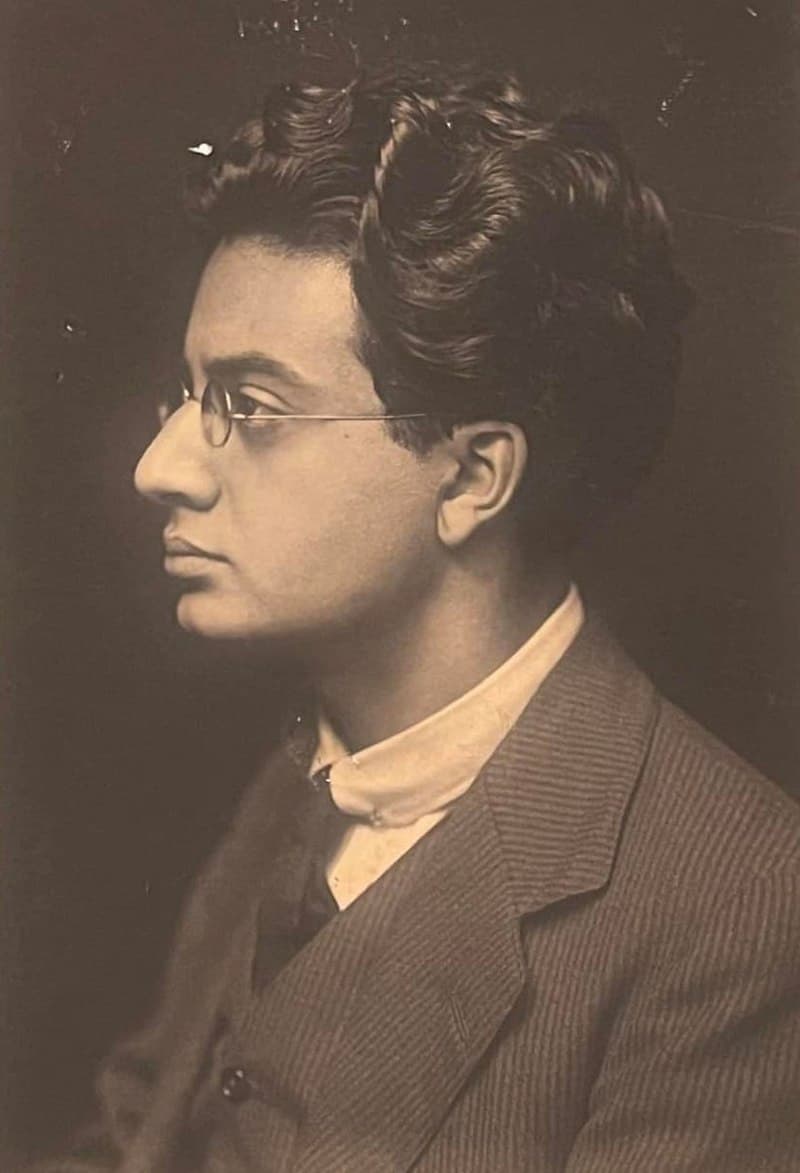

Giuseppe Ferrata, 1924

For a highly effective and elegant showpiece we now turn to a “Minute Waltz” transcription by Giuseppe Ferrata (1856-1928). He came from a family of small landowners, and originally wanted to become a Roman Catholic priest. However, by the age of 14 he changed his mind and started to pursue training as a musician and composer at the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. He studied piano with Giovanni Sgambati and musical composition with Antonio Terziani. He auditioned for Franz Liszt who took him on as a student for three years. As Liszt once said, “Ferrata is now an artist of great distinction, and bids fair to distinguish himself still further.” Ferrata immigrated to the United States in 1892, and he held a series of teaching posts. Ferrata was also an inventor with three patents to his name. His musical patent involves a piano attachment which enables the piano to bow a string like a violin, and produce a sound like a violin.

Aleksander Michałowski: Paraphrase on the Waltz in D-Flat Major, Op. 64, No. 1

Aleksander Michałowski: Paraphrase on the Waltz in D-Flat Major, Op. 64, No. 1 (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

Aleksander Michałowski

The Polish pianist, composer, and pedagogue Aleksander Michałowski (1851-1938) studied with Ignaz Moscheles and Carl Reinecke at the Leipzig Conservatory. Michałowski was said to have had enormous technical abilities, and he devoted a lifetime to the study of Chopin’s works. A contemporary wrote, “As an interpreter of Chopin he created a certain style of rendering the composer’s works which found many imitators. It consisted of the chiseling of swift passages and stressing their elegance in smoothing the edges of sharper expressive climaxes, in lending Chopin’s works the air of almost drawing-room sentimentality. And yet this slight sentimentality was always under the strict control of moderation, instrumental purity, and good taste.” Michałowski always emphasized the importance of contrapuntal playing, and he understood that contrapuntal principles were most important for an understanding of Chopin’s work. Just listen to the middle section of his “Minute Waltz” paraphrase, where the theme of the middle section is contrapuntally superimposed against the main theme of the work.

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji: Pastiche on the Minute Waltz of Chopin

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji: Pastiche on the Minute Waltz of Chopin (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892-1988) was largely self-taught as a composer, and he remained an outsider “owing to his anti-establishment views, racial origins, homosexuality, and his self-described mania for privacy.” He played the piano only seldom in public, and he was not really considered a virtuoso. Commentators, however, did suggest, “he had marvelous technique, produced beautiful sound, and sported unparalleled energy.” His compositions often relied on “Baroque structure, post-Romantic grandeur and scope, complex and free harmony and tonality, continuous evolution of long melodies, asymmetrical phrases unaffected by dualistic formal patterns, Impressionistic colour, bountiful ornamentation and virtuosity, and deep mystical or religious qualities.” For Sorabji, the acts of composition and performance were intensely sacred, and the “best music to be suitable only for initiates, not the uncultured masses.” And no doubt, you can hear his kind of eccentricity in the “Pastiche on the Minute Waltz by Chopin.”

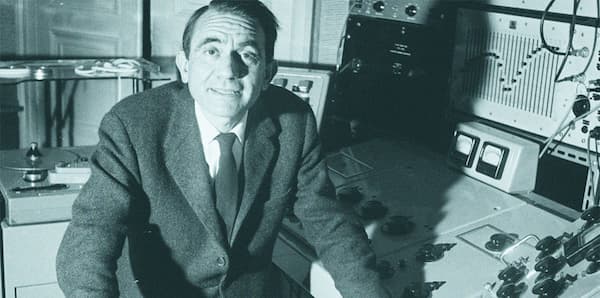

Eugen Cicero: “Minute Waltz”

Eugen Cicero

Because it is such a popular tune, Chopin’s “Minute Waltz” did not get stuck in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It easily crossed genres and became part of popular musical expressions. Joseph Furstenberg who appeared under the stage name “Joe Furst” wrote a very funny Showpan Boogie, and the Romanina-German jazz pianist Eugen Cicero placed the “Minute Waltz” halfway between the classical and jazz idiom. Cicero started his piano lessons at the age of four, and publically played his first Mozart piano concerto with orchestra at age six! However, he was bored with the idea of becoming a conventional concert pianist and got interested in jazz instead. He was soon dubbed “Mister Golden Hands,” and he has produced over 70 recordings over his career. His most popular disk was called “Swinging the Classics,” and it included a delightful arrangement of Chopin’s Waltz Op. 64, No. 1. I think the “Minute Waltz” will continue to inspire performers and composers, and I can’t wait to hear new and contemporary versions inspired by the 21st century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter