“I am in a prison: One wall is the avant-garde, the other is the past, and I want to escape”

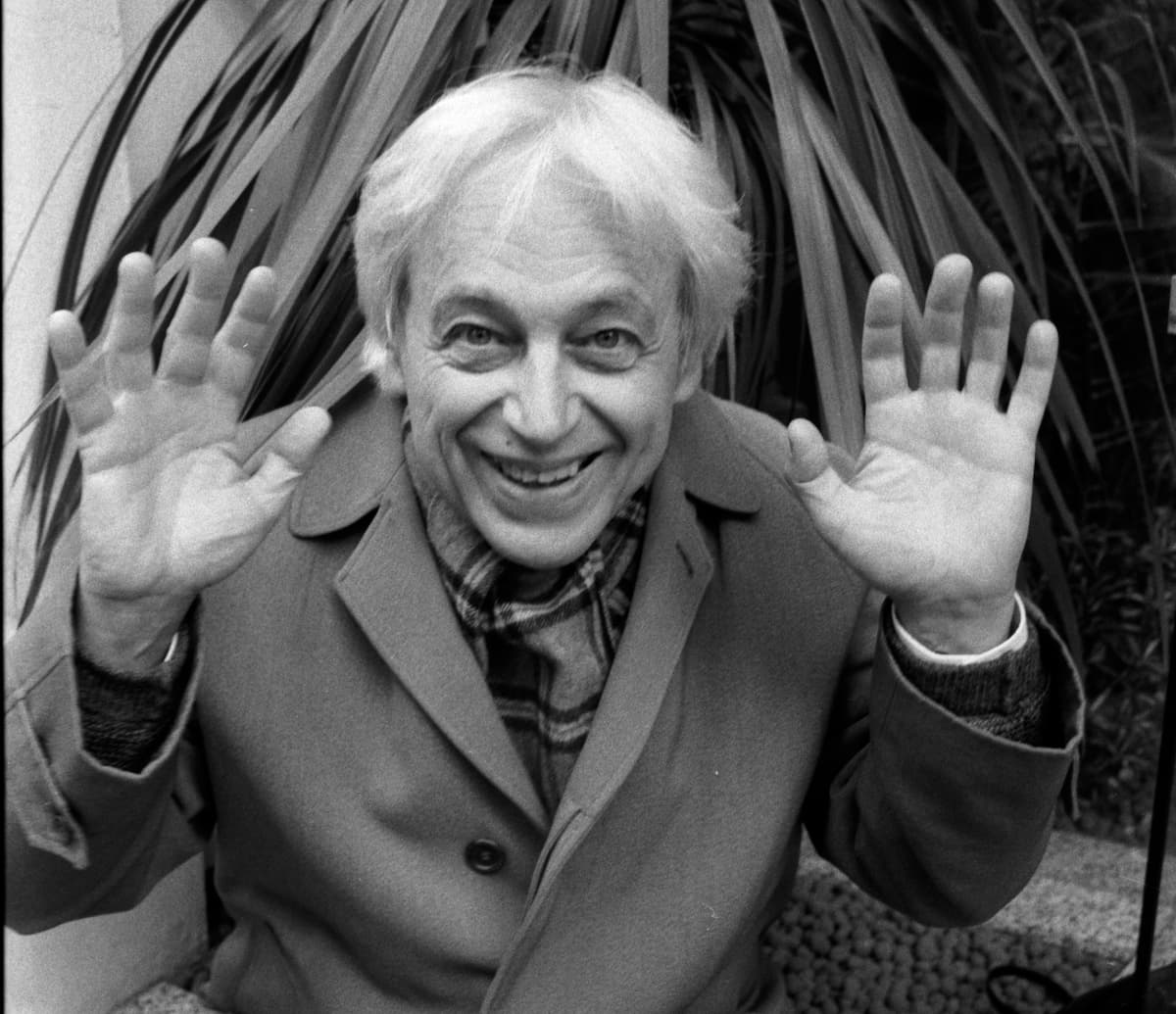

György Ligeti

100 years ago, on 28 May 1923, the Hungarian composer György Ligeti (1923-2006) was born in the little Transylvanian town of Diciosânmartin, currently Tîrnăveni, located in Romania. The featured quote might well represent a microcosm of Ligeti’s life, as he initially suffered under Nazi and Stalinist tyrannies. He left Hungary for Western Europe after the Russian invasion in 1956, but “was confronted by another stern ideology, that of the Darmstadt-Cologne musical avant-garde.” And while he enjoyed the liberating musical possibilities, he remained highly suspicious of serial orthodoxy.

György Ligeti in the 1960s

Initially, he attempted to escape by developing a process of interweaving different strands of sound into a complex polyphonic fabric, “deriving the shape and momentum of the music from barely perceptible changes in timbre, dynamics, density, and texture.” And while his enthusiasm for science and his insatiable curiosity were constant sources of inspiration and question, he found his true escape in non-European musical cultures. “All culture,” he once wrote, “the whole world, are material of art.” As a scholar writes, “Always paradoxical, he found this music of the world enhancing his sense of himself as musically a Hungarian.”

György Ligeti: String Quartet No. 2

Ligeti hailed from a musical family of some artistic distinction, and he initially studied with Ferenc Farkas at the Kolozsvár Conservatory. He composed his first works at the age of 14, and in the following years wrote pieces for piano and other instruments, a string quartet, songs for voice and piano, unaccompanied choral works, and an unfinished symphony. He continued his musical education by taking private lessons with the pianist Pál Kadosa in Budapest. Ligeti entered the academy of music in Budapest, studying with Farkas, Sándor Veress, and Pál Járdányi. Upon graduation, he embarked on an extended tour of Romania, transcribing hundreds of folk songs. As he later explained, “all my compositions dating back to Hungary show Bartók’s influence very strongly, and to a lesser extent that of Stravinsky and of Berg’s Lyric Suite.

György Ligeti: 4 Early Piano Pieces (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

As Ligeti explained, “In the early 50s, I began to feel that I had to go beyond Bartók. It did not mean repudiating him stylistically. What I felt I had to abandon were traditional forms, a musical language of the traditional kind, the sonata form. I wanted to get away from all ready-made forms, which Bartók took seriously and had learned from late Beethoven and from Liszt. The sonorities were still valid for me, also his chromaticism, but I had to get beyond formal structures.” Ligeti was beginning to make his mark as a composer, and the political and cultural situation in Hungary demanded a steady output of choral settings in folk style. As a biographer wrote, “between 1949 and 1953 came a period of despotism in Hungary when musical innovation was as impossible as political dissent.” Yearning to expand his musical horizons, Ligeti considered only a few compositions written before 1956 worthy of publication.

György Ligeti: Six Bagatelles for Wind Quintet

Ligeti fled to the West after the Hungarian uprising of 1956, and he got acquainted with the latest trends in Western music. Primarily stationed in Vienna, he spent a year in Cologne and became fascinated by Anton Webern. “He found a model of manifest construction allied with extreme expressive effect,” and he wrote specific analysis on works of total serialism. He worked at the West German Studio for electronic music, and he began teaching international holiday courses in Darmstadt. The premiere of his first orchestral work completed in the West caused a sensation. Apparitions, first heard at the 1960 International Society for Contemporary Music Festival brought international recognition to the composer. A biographer writes, “Listeners were fascinated above all by its bold and original new sound world, which had nothing in common with the serialism prevalent at that time.” Ligeti had realized his dream of “unmeasured rhythm, fantastical complexity, and sonic drama.”

György Ligeti: Apparitions

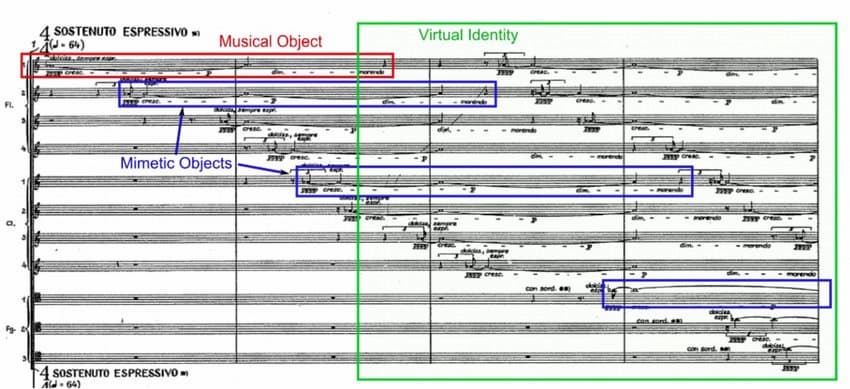

During the 1960s, Ligeti approached musical texture via counterpoint. As he explained, “you cannot actually hear the polyphony. You hear a kind of impenetrable texture, something like a very densely woven cobweb. However, the polyphonic structure remains hidden in a micropolyphony.” He later offered the following observations on his compositional process. “The harmonic crystallization within the area of sonority leads to an intervallic-harmonic thought process that is thereby radically different from traditional and also atonal harmony.

György Ligeti’s Lontano

Technically speaking, this is achieved with the aid of polyphonic methods: fictive harmonies emerge from a complex vocal woven texture; gradual opacity and new crystallisations are the results of discrete alterations in the individual parts. The polyphony in itself is almost imperceptible but its harmonic effect represents the intrinsic musical action: what is on the page is polyphony, but what is heard is harmony.” Lontano (In the Distance) of 1967 depicts a haunting orchestral dreamscape that unfolds in vast sonic waves. Despite its avant-garde surface, the work is closely connected to the central European musical tradition, as the composer compared the gradually shifting kaleidoscope of colour to the majestic unfolding of Bruckner’s eighth symphony.

György Ligeti: Lontano

During his time as visiting professor at Stanford University in 1972, Ligeti got to know the music of Reich and Riley, and he expanded his vocabulary by including microtones and “well-defined melodies that emerge from and fold back into more characteristically Ligetian textures of held chords and fast arpeggios.” Ligeti accepted a permanent appointment in Hamburg, and his opera Le Grand Macabre, based on a play by the Belgian dramatist Michel de Ghelderode, represents a synthesis of textures and styles. Ligeti called it an “anti-anti-opera,” with death arriving in a fictional city to announce the end of the world. Ligeti’s music does use quotations in a pastiche or collage environment, and quasi-diatonic chords “estrange and subvert their harmonic implications.”

György Ligeti: Le grand Macabre, “Mysteries of the Macabre”

While Le Grand Macabre was enjoying success across Europe, Ligeti struggled with a crisis in musical evolution. A scholar writes, “by the late 1970s the avant-garde to which he had been attached, however skeptically, was no longer functioning as such: the time of shared ideals was over, and instead of being a challenge to established musical culture, the postwar generation had become the new establishment.” However, Ligeti had no intention of a postmodern trend to return to the forms and styles of the previous century. Instead, he started to explore European culture as part of a global network. After a long period of silence, Ligeti composed his Horn Trio in 1982. Written in homage to Brahms, “whose Horn Trio remains unequalled of its kind in the musical heavens,” it nevertheless does not contain quotations or direct influences of the music of Brahms. “My trio is,” according to Ligeti, “in construction and expression, music for our time.”

György Ligeti: Horn Trio

During the last decades of his life, folk music once again proved to be a great source of inspiration. Expanding the limits of tonal music, Ligeti made an intensive study of the folk music of the Balkans and Africa, especially sub-Saharan music. It was the rhythmic richness of polyrhythmic drumming and the coexistence of server layers of sound that opened up unfamiliar possibilities and created a new imaginary musical folk universe. Over a period of roughly seventeen years, Ligeti composed eighteen Études pour piano, works that are beyond the abilities of mere mortals.

György Ligeti’s Piano Concerto

Ligeti finally had found his escape, effectively creating a new pianistic vocabulary while remaining exuberantly himself. He completed a piano and violin concerto in the same vein, but his health deteriorated and he died in Vienna on 12 June 2006. Ligeti has been described as “one of the most innovative and influential among progressive figures of his time.” And it all originated in his general attitude not only to music but to all other areas of his life as well. As he once disclosed in an interview, “I don’t take anything for granted. When something is asserted and it sounds good, my immediate reaction is to go below the surface to see what reality I find there.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter