If you find yourself in Vienna with a bit of free time on your hands, you might well consider taking a short excursion to Grinzing. This charming old wine village still preserves architectural objects from Roman times, but it is most famous for taverns where local winemakers serve new wine, simple foods and local music. Such taverns are called “Heuriger,” and Mozart and Beethoven were great fans.

Grinzing © grinzland.com

This outlying district of Vienna also features a small but well-kept cemetery, and it might surprise you to know that it houses the grave of Gustav Mahler. The grave itself possesses a stark simplicity, consisting of little more than a patch of grass flanked by low hedges. At the rear, a large stone block contains only the name Gustav Mahler carved into its top. As Mahler had stated, “any who come to look for me will know who I was and the rest don’t need to know.” How then did Mahler end up in Grinzing?

Gustav Mahler: Songs on the Death of Children

Last Concert in New York

Last known photograph of Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler conducted his last concert in Carnegie Hall in New York on 21 February 1911. He was running a very high fever, and his throat became seriously inflamed. Mahler briefly recovered, but when his fever returned, his doctor, Joseph Fraenkel, called a specialist. Dr. George Baehr arrived to draw some blood. After 4 or 5 days of incubation in the laboratory, the plates revealed numerous bacterial colonies. The diagnosis of subacute bacterial endocarditis was devastating.

Mahler knew that this disease was particularly dangerous for people with defective heart valves and that before the advent of antibiotics, almost no one survived. Alma blamed the American adventure for her husband’s trouble. As she wrote, “In Vienna, my husband was all-powerful, even the Emperor did not dictate to him, but in New York, he had ten ladies ordering him about like a puppet.”

Gustav Mahler: Songs of a Wayfarer, “When my sweetheart is married” (arr. A. Schoenberg) (Roderick Williams, baritone; Attacca Quartet; Virginia Arts Festival Chamber Players; JoAnn Falletta, cond.)

Journey to Paris

Alma Mahler

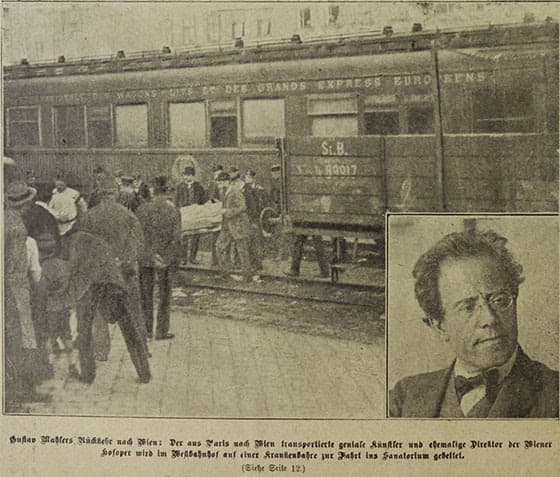

And while Mahler did not give up hope, talking about resuming the concert season, he expressed a wish to die in Vienna. To that end, the Mahler family and a permanent nurse left New York on board SS Amerika bound for Europe on 8 April. They reached Paris ten days later, where Mahler entered a clinic at Neuilly. The diagnosis and prognosis were confirmed, and on 11 May, Mahler was taken by train to Vienna. The journey, according to Alma, was that of a dying king, with journalists coming to the door at every station in Germany and Austria asking for the latest bulletin.

The writer and diplomat Paul Zifferer relates Mahler’s arrival as mortally ill returning to Vienna. His report appeared in the local paper on 13 May 1911. “The Orient Express thundered into the Hall of Vienna’s West Train station… The windows of one of the carriages remain darkened, and everyone who passes instinctively lowers their voices…They have come to greet Gustav Mahler, who, after a long journey, has returned home to Vienna. Only visible from afar, where nobody can see, they want to spare him any public commotion.”

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C minor, “Resurrection” IV. Urlicht (Kirsten Dolberg, contralto; Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; Leif Segerstam, cond.)

Arrival in Vienna

Mahler’s arrival in Vienna

“Medics enter the carriage, and the automobile for the invalid is parked right by the tracks. They attempt to move a stretcher into the carriage, but no amount of turning or twisting appears to work, with all attempts proving futile… Suddenly, we notice some movement in the carriage carried by two men; we can see Gustav Mahler through the windows. His ravaged body is dressed in a grey summer suit. His noble hands rest gently on the shoulders of the two men supporting him.

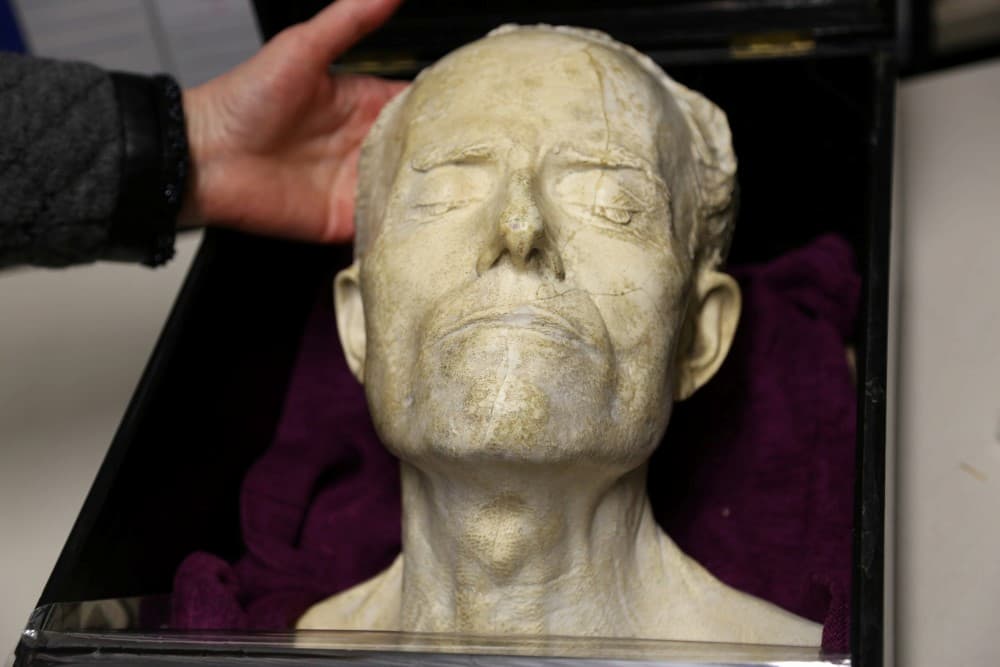

At first, we only see the back of his head, the black wiry hair, the narrow boy-like shoulders, but suddenly the patient turns his head, and one recognises the contours of his face: the broad steep forehead, in which locks of hair defiantly fall, the pointed nose above his thin, firmly pressed lips and the wilful chin. His face is pale and exudes both suffering and fortitude. His movements are defiant, radiating tension and energy, and an intense will to live. His face radiates determination, yet what we see is only a mask.

As they place the patient onto the stretcher, there is a painful movement on his lip that only lasts a few seconds. Immediately afterward, his determination takes over again, his muscles tighten, and a red blanket that picks up the sun is tucked around him. The wind plays gently in his hair as if wishing to caress him. And then, Gustav Mahler raises his eyes glasses through which he so often shot his stern, unyielding looks are missing. An undefinable flickering in his eyes appears, searching and yearning, looking in the distance towards the city growing pink in the first signs of eventide.”

Gustav Mahler: Rückert Lieder, “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen”

Mahler at the Löw Sanatorium

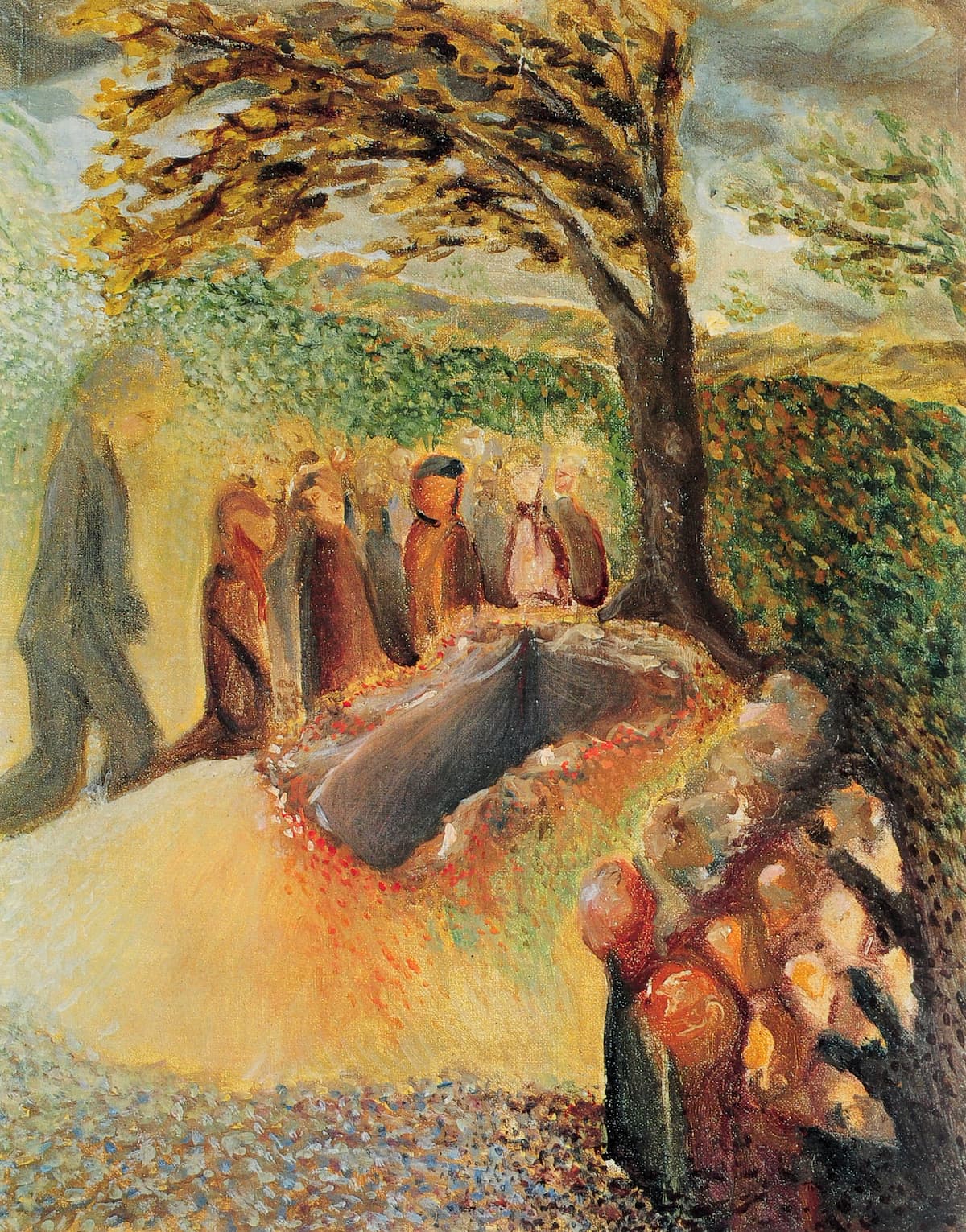

Arnold Schönberg: Burial of Gustav Mahler

Mahler was taken straight to the Löw sanatorium, a hospital Mahler knew well as he had been operated on there a decade before. Vienna went into mourning, but much of it was pretentious. Berta Zuckerkandl wrote to her sister, “all the people who had fought Mahler in his opera days now shed crocodile tears when he returned on a stretcher.” With the press issuing daily bulletins from his bedside, sentimental anecdotes were told everywhere.

Hundreds had come to the sanatorium during this brief period to show their admiration of the great composer, but Mahler had already developed pneumonia and slipped into a coma. As his legs were swelling, he received radium treatments and morphine for his general ailments, and Gustav Mahler died around 11 pm on 18 May 1911.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 1 in D Major, IV. “Funeral March” (North German Radio Symphony Orchestra; Thomas Hengelbrock, cond.)

Funeral in Grinzing

Mahler’s funeral, 1911

At 5 pm on 22 May 1911, Mahler’s coffin was taken from the Grinzing chapel by six bearers of the undertaker to the hearse outside the gates of Grinzing cemetery. A priest led the procession, and on both sides of the hearse walked employees of the funeral home with candles. Alma Mahler, as advised by her doctor, was not present.

The parade moved along narrow paths and meandered over the fields, surrounded by high hedges of greenery and roses on the left and a potato field on the right. As the procession reached the Grinzing parish church, it started to rain heavily. Mahler’s coffin was covered with a cloth and placed before the altar while hundreds of interesting people were already waiting at the church.

Death mask of Gustav Mahler

Everybody was dressed in black, and only the sound of the bell tower was heard as the coffin arrived at the open grave. Mahler had requested a solemn ceremony, but a great ocean of flowers covered the churchyard, and roughly 400 wreaths had been delivered. Among the mourners were Arnold Schoenberg, Bruno Walter, Alfred Roller, the Secessionist painter Gustav Klimt, and representatives from many of the great European opera houses.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor, I. “Funeral March” (Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

Reception

Grave of Gustav Mahler

The London Times, representatively, was unsure of Mahler’s achievements. While his triumphs as a conductor were loudly praised, the value of his compositions was clearly in doubt. As they wrote, “his symphonies are undoubtedly interesting in their union of modern orchestral richness with a melodic simplicity that often approached banality, though it is too early to judge their ultimate worth.”

Mahler’s audiences, according to Leonard Bernstein, “could not or would not face up to the brutal truth that his music reflected Western society in decay. It was only after half a century or more of horrors ranging from Auschwitz to the arms race that we can finally listen to Mahler’s music and understand that it foretold all.”

Mahler had prophesied “my time will come” in a 1902 letter to Alma, but it was only during the 1960s that he was rescued from almost total neglect by a “generations sadder and more knowing than his own.” Mahler, as requested, was buried next to his daughter Maria (Putzi). Alma Mahler-Werfel died in New York City on 11 December 1964, and she was buried on 8 February 1965 in the Grinzing Cemetery as well. She shares the grave with her daughter Manon Gropius, just a few steps away from Gustav Mahler.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter