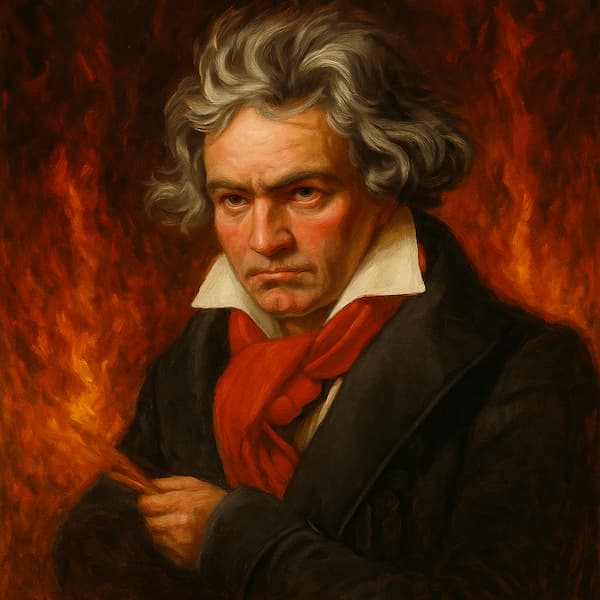

Marian Anderson

(1897-1993)

Credit: http://www.philipcaruso-story.com/

Jus’ Keep on Singin’

Marian Anderson’s performance

Credit: http://www.firstladies.org/

After attending high school, Anderson naively applied to the Philadelphia Music Academy, (University of the Arts) which was at the time an all-white music school. “We don’t take colored,” said the woman admissions officer. Anderson persevered.

She continued to perform and study privately, winning competitions and even appearing in Carnegie Hall in 1928, but the struggle with racial prejudice was such that it led her to try her luck in Europe. It was a gamble that paid off. Paris had an impartiality that Marian hadn’t encountered before and Scandinavians were very open-minded too. Maestro Arturo Toscanini when he heard her sing remarked, “a voice heard once in a hundred years.” This endorsement opened many doors for the young artist.

Bellini “Norma”

Marian Anderson broke the color barrier at the Metropolitan Opera in 1955 when she starred in Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera.

Credit: Sony Classical Archives

Sibelius: 5 Songs, Op. 37: No. 5. Flickan kom ifran sin alsklings mote (version for voice and piano)

Anderson’s dignity and sincerity as an artist brought tears to the eyes of her devotees. After a recital in Paris the great American manager Sol Hurok witnessed the effect. He invited Anderson to the U.S. for seven concerts beginning with New York’s Town Hall. Anderson’s rave reviews had preceded her. Everyone flocked to the concert curious to hear what the fuss was about.

Out she came onto the stage with a stunning, elegant presence. Then she opened her mouth.

Her extraordinary voice impressed the critics who called her “one of the great singers of our time.” But many “didn’t want to hear that kind of singing from a Negro,” said Todd Duncan, (George Gershwin’s preferred baritone for Porgy in the first performance of Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess, a role he did 1800 times.) African Americans should stick to vaudeville and spirituals not art song, or lieder in foreign tongues!

Ave Maria with Stokowski

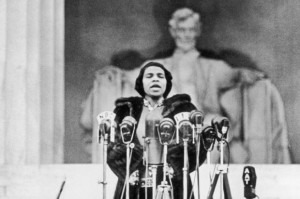

American opera singer Marian Anderson performs

on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in

Washington, DC on April 9, 1939.

Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

But Anderson’s contracts posed issues. Some concert halls didn’t allow black performers. And of those that did, many had segregated seating. Some allowed African American audience members to sit only in the back row; a barrier vertically divided other halls and some halls wouldn’t allow African Americans inside at all. Anderson refused to perform in segregated theaters.

Laws regarding housing and transportation for people of color plagued her wherever she appeared. Every hotel and bus was a problem. Where could she stay? Where could she eat? (Sometimes she’d munch on a sandwich outside.) How could she do laundry? Where could she practice? —All privileges we take for granted today. Due to this appalling discrimination none other than Albert Einstein, who was a great champion of tolerance, hosted Anderson many times. And she? Marian always maintained her dignity making many recordings of diverse repertoire often including American songs and spirituals.

Traditional

Dett, Robert Nathaniel – arranger

Poor Me

People clamored to hear her. Todd Duncan, almost in jest, suggested a large place— Constitution Hall in Washington. After Hurok’s request for a date was turned down repeatedly, news got out. The public was scandalized. The Daughters of the American Revolution who owned the hall had a “white artists only” clause in their contracts. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt came to the rescue. The 1939 Easter Sunday performance would take place at the Lincoln Memorial in front of countless thousands of people. A self-possessed Anderson appeared launching into My Country, ‘Tis of Thee. There was not a dry eye in sight.

Marian Anderson with President John F. Kennedy and Franz Rupp, Marian’s accompanist

Credit: http://www.phyllissimsphotography.com/

Verdi: Un Ballo in maschera

Act I: Zitti … l’incanto non dessi turbare – Re dell’abisso, affrettati (Ulrica)

She became the idol and mentor of other greats who followed including Shirley Verett, Leontyne Price and Jesseye Norman, who said, “’This can’t be just a voice, so rich and beautiful.” ‘It was a revelation. And I wept.’”

Anderson was the recipient of numerous awards including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Kennedy Center Honors, National Medal of Arts and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. President Eisenhower selected her as a delegate to the United Nations. But her proudest moment was when she called the department store where her mother furiously scrubbed floors to say, “ My mother won’t be in for work today, or anymore.”

Marian Anderson is truly an inspiring icon whose music transcended all boundaries. For more read her autobiography My Lord What A Morning, and view the documentary below full of mesmerizing interviews and amazing performances— time well spent.

Documentary