Ralph Vaughan Williams’ quintessential work for violin and for the summer is The Lark Ascending. We are so familiar with its trilling and rising skylark, personified by the violin, who takes flight above a quiet chamber orchestra.

Vaughan was inspired by a poem by George Meredith, written in 1881. The poem is 122 lines and RVW copied out 12 lines from the beginning, middle, and end of the poem and put them at the head of the score.

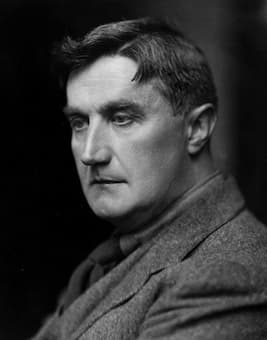

E.O. Hoppé: Ralph Vaughan Williams, ca. 1920

He rises and begins to round,

He drops the silver chain of sound,

Of many links without a break,

In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake.

For singing till his heaven fills,

‘Tis love of earth that he instils,

And ever winging up and up,

Our valley is his golden cup

And he the wine which overflows

to lift us with him as he goes.

Till lost on his aerial rings

In light, and then the fancy sings

We are used to the sound of the violin over a lush instrumental background, which swells up behind our little violin-bird. When Vaughan Williams first wrote the work, however, he wrote it for violin and piano. This was in 1914.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: The Lark Ascending (version for violin and piano) (Jennifer Pike, violin; Martin Roscoe, piano)

He set the work aside as WWI began but it was one of the first pieces he took up again afterwards. Its first performance was in December 1920 and the same violinist, Marie Hall, was also the soloist for the premiere of the orchestral version 6 months later. Marie Hall is also the dedicatee of the work, having also given the premiere of Elgar’s Violin Concerto. Hall was an international violin celebrity before the war.

Here we finally have the richer sound that we’re more familiar with.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: The Lark Ascending (Iona Brown, violin; Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Orchestra; Neville Marriner, cond.)

Marie Hall

In his original orchestration, Vaughan Williams scored for strings, two flutes, one oboe, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, triangle and full strings.

He also created a version for chamber orchestra, where he cut the performing forces even farther: one each of flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn and triangle, with three or four first violins, the same of second violins, two violas, two cellos and one double bass.

In his musical setting, Vaughan Williams makes his music work double: it is both the bird’s song and the bird’s flight. He doesn’t set the poem to music, but sets the ideas and image of the poem. We can hear the bird circling up through the air, into the light of the sky, until we lose him to sight.

Other interesting versions include violin and organ where, unlike the piano version, the different voicing in the organ brings more depth to the keyboard performance.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: The Lark Ascending (arr. D. Briggs for violin and organ) (Rupert Marshall-Luck, violin; David Briggs, organ)

An even more interesting version is for violin and chamber choir. One interesting innovation the arranger, Paul Drayton, made to the choral version was the addition of text to the music. Drayton set only the 12 lines that Vaughan Williams chose for the folk-song–like middle section (06:27).

Ralph Vaughan Williams: The Lark Ascending (arr. P. Drayton for violin and mixed choir) (Jennifer Pike, violin; Swedish Chamber Choir; Simon Phipps, cond.)

A reviewer for The Times at the orchestral premiere called out the work as being something that was neither of yesterday or today, evoking the ‘clean countryside, not the sophisticated concert-room’ and that is how we hear it to this day. Another writer said that even the cadenzas were like no one else’s work – it was pure song.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter