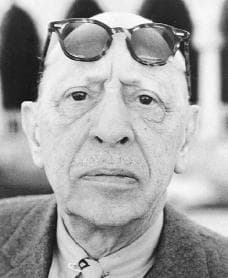

Igor Stravinsky

At the age of 88, Igor Stravinsky died on 6 April 1971 at his apartment in New York City. The composer had been in frail health for years but returned much refreshed from a two and a half month holiday at Evian, France, in August 1970. Beginning in 1967, the composer had suffered a series of arterial strokes, and had been “in and out of hospitals ever since.” In that year, he directed Pulcinella in Toronto, which turned out to be his last public concert. He also completed the last recordings of his music in New York, and subsequently worked on a number of arrangements of works by other composers, including Lieder by Hugo Wolf and the chorale variations of J.S. Bach. Stravinsky was admitted to Lenox Hill Hospital with pulmonary edema on 18 March 1971, and his “stay there was extended because his new 10-room apartment at 920 Fifth Avenue overlooking Central Park was being decorated.” He was finally released on 30 March, and his nurse gave him a tour of the apartment in his wheelchair. Apparently, Stravinsky said to her “How lovely. This belong to me, it is my home.”

Bach/Stravinsky: “Vom Himmel hoch”

Stravinsky in Venice

Stravinsky’s death still came as a surprise to his doctors, as “he apparently had rallied after breathing complications had developed over the weekend.” Dr. Theodore Lax, the composer’s physician throughout his recent illness, was not present at the time of death. He arrived soon thereafter and ruled the cause as heart failure. At Stravinsky’s bedside were his wife Vera, his musical assistant and close friend Robert Craft, his personal manager Lillian Libman, and his nurse Rita Christiansen. Robert Craft had been Arnold Schoenberg’s secretary until 1947, and then went to work for Stravinsky. According to Miss Libmann, “Mr. Craft was too shaken by the death to speak to callers, but wished it known that he had lost the dearest friend he ever had.” As the New York Times reported, “The composer’s body was taken to Frank E. Campbell’s at Madison Avenue and 81st Street, and a Russian Orthodox service was held there Friday at 3 PM., with the Rev. Alex Schmenin officiating.”

Igor Stravinsky: Requiem Canticles (Gregg Smith Singers; Ithaca College Concert Choir; Columbia Symphony Orchestra; Robert Craft, cond.)

Stravinsky expressly wished to be buried in Venice, specifically in the Russian corner of the cemetery of San Michele. Scholars have suggested that Stravinsky was not “moved by historical precedents like Richard Wagner’s death or the death and burial of his close friend Sergei Diaghilev’s in the city, but decided on Venice as his final resting place for aesthetic reasons; Venice was the city that he loved the most.” Stravinsky did have a particularly close attachment to the city of Venice. The Rake’s Progress was first performed in Venice, as was Threni. In 1956, the Basilica di San Marco opened its doors to Stravinsky’s music. On 13 September, his “Canticum sacrum ad honorem Sancti Marci nominis” for tenor, baritone, choir and orchestra was premiered in the Basilica during the 19th Biennale Musica festival. That complex musical composition, mirroring the countless domes of the Basilica, is dedicated to Venice, in praise of its Patron Saint Mark.

Stravinsky expressly wished to be buried in Venice, specifically in the Russian corner of the cemetery of San Michele. Scholars have suggested that Stravinsky was not “moved by historical precedents like Richard Wagner’s death or the death and burial of his close friend Sergei Diaghilev’s in the city, but decided on Venice as his final resting place for aesthetic reasons; Venice was the city that he loved the most.” Stravinsky did have a particularly close attachment to the city of Venice. The Rake’s Progress was first performed in Venice, as was Threni. In 1956, the Basilica di San Marco opened its doors to Stravinsky’s music. On 13 September, his “Canticum sacrum ad honorem Sancti Marci nominis” for tenor, baritone, choir and orchestra was premiered in the Basilica during the 19th Biennale Musica festival. That complex musical composition, mirroring the countless domes of the Basilica, is dedicated to Venice, in praise of its Patron Saint Mark.

Cemetery of San Michele in Venice

In the event, a flower-decked gondola carried the body of composer out into the Venetian lagoon to be buried amid the Cyprus trees and roses on the island cemetery of San Michele. His final resting place is just a couple of steps away from the grave of his close friend and collaborator Sergei Diaghilev, and his tomb is forcefully simple, a horizontal slab with the composer’s name across the top and a cross toward the bottom. Vera Stravinsky is beside him, her grave identical in design.

Igor Stravinsky: Canticum sacrum

Graves of Igor and Vera Stravinsky

News of the composer’s death spread quickly, and the Guardian called him “the first truly modern composer. He made a great deal of money out of music…He was a gawky, birdlike figure on the rostrum, but a compelling one.” Pierre Boulez, explaining the composer’s legacy wrote, “The death or Stravinsky means the final disappearance of a musical generation which gave music its basic shock at the beginning of this century and which brought about the real departure from Romanticism. Something radically new, even foreign to Western tradition, had to be found for music to survive, and to enter our contemporary era. The glory of Stravinsky was to have belonged to this extremely gifted generation and to be one of the most creative of them all.” And his longtime friend George Balanchine, head of the New York City Ballet, eulogized “I feel he is still with us. He has left us the treasures of his genius, which will live with us forever.” On the other hand, the philosopher and cultural critic Theodor Adorno had previously dismissed Igor Stravinsky as a “dummy civil servant, psychotic, infantile and devoted to making money.” Stravinsky was generally ignored in the period following his death, but today we understand his artistic achievements as the result of his multiple exiles. As he famously articulated in his Memories and Commentaries, he “wanted to be influenced.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Igor Stravinsky: “The Owl and the Pussy Cat”