A product of a 19-year-old composer, George Enescu’s Romanian Rhapsody No. 1, completed in 1901, is thought to be a loosely connected set of episodes sources on folk dances and folk songs. But although these are seemingly ‘as found’, Enescu has actually modeled his work on Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies, and like Liszt, chose his music examples from popular, rather than folk, sources.

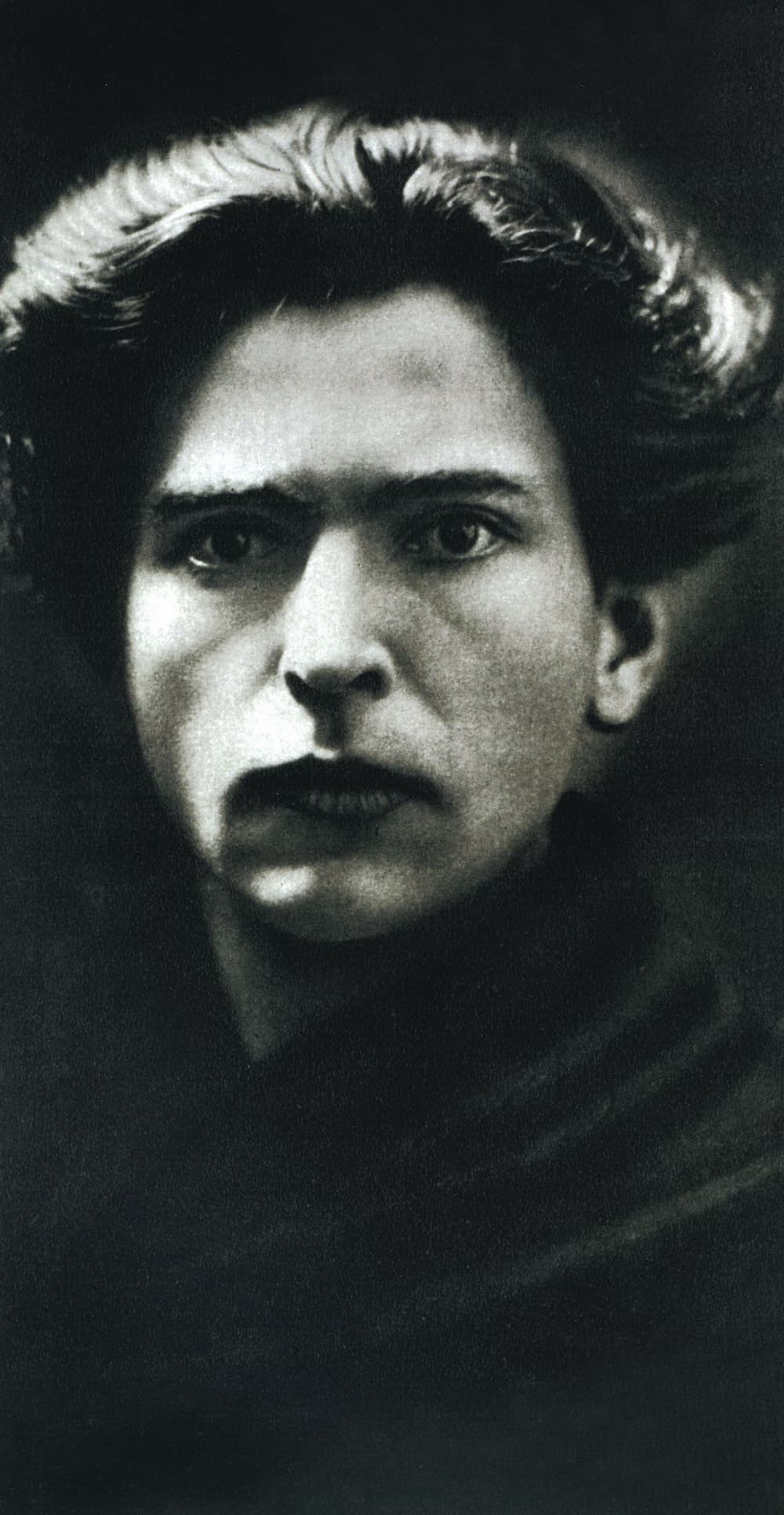

The young George Ensecu

The rhapsodies (he wrote No. 2 that same year) are the emergence of Enescu’s national voice. The melodic tunes are not weighed down with excessive Romantic harmonies, or heavy textures. They stand alone and connect with each other through motives that are derived from Enescu’s own folk-inspired melodies.

The First Romanian Rhapsody opens with a real folk song that sets the tone for what will follow: – ‘I want to spend my shilling on drink’. From that beginning, dance after dance appears, whirling faster with increased sound and speed. One writer compared the work to that of the original rhapsodists, who wandered the Greek countryside reciting fragments (ever more exciting) of the Homeric epics. The application of the word to music comes from Liszt.

The opening is like coming upon a village band, with the solo clarinet and oboe trying out bits of melody. Traditional instruments had to be replaced with more standard orchestral instruments, hence the first harp stands in for the cimbalom and its tremolo sound and the second harp takes on the role of the strumming chordal guitar. Gypsy-style fiddling challenges the violins and they rise to the occasion, playing faster and higher.

George Enescu: 2 Romanian Rhapsodies, Op. 11 – No. 1 in A Major (Orchestre National de France; Cristian Măcelaru, cond.)

Careful listening will show deliberate crudities and mistakes written into the music: ‘a piccolo which comes in half a beat late but manages to correct itself within a couple of bars, and an amazing passage of organised argumentative chaos in which the woodwind and brass cannot agree either on which version of the tune they are supposed to be playing or on when and how to play it (the piccolo intervenes and makes matters worse)’. We’re used to this kind of sound from Charles Ives’ imitations of the village bands of his youth, but in European orchestral music at the turn of the century, this was unknown.

Other melodies that were the basis for some of Enescu’s melodies were Hora lui Dobrica, the song Mugur, mugurel (“Little Bud”) and the lively Ciocârlia (“The Lark”). The last was a tune composed by Anghelus Dinicu for the pan flute but which his son, Grigoraș Ionică Dinicu brought into the violin world.

E. Joaillier: Romanian composer George Enescu at the piano, 1930

Enescu’s arrangements and orchestrations continue to drive up the excitement level to the very end until when it can’t get more pressured, it all lets off at the end and seems to relax with a little clarinet melody until, at the very last minute, it spins off into utter exhaustion.

The whirling First Rhapsody was taken up by conductors including Toscanini, Stokowski, Doráti, Celibidache, Rodziński, Rozhdestvensky, and Järvi; its influence on modern sound can include David Arnold and Michael’s Price’s music for the television series Sherlock.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter