The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo

Peoples and Cultures around the world have always been asking the fundamental question of human awareness, where did we come from and why are we here? Attempting to answer these fundamental questions, the human imagination has produced stories of creation as wonderfully varied as culture itself. Native Americans tell tales of a raven accidentally creating man from a pea pod, while the Kabbalah—a school of thought in Jewish mysticism—teaches that light has always existed, and its need to share created a vessel, which created all life, as we know it. For Hindus, there is no single story of creation but multiple creation stories that tell of cyclic creation and destruction, while the Genesis Creation casts out Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden after Eve ate from the Tree of Knowledge.

Haydn’s The Creation

A good many of these creation stories proceed from chaos and nothing to describe the subsequent ordering of the cosmos. But what does nothing sound like in music? That’s the question Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) asked himself when starting work on his oratorio The Creation. Haydn’s “Representation of Chaos,” starts with a union note played by the full orchestra. It has no harmony, no dissonance, no melody and no rhythmic pulse, only an extended decrescendo on this single note. As a critic wrote, “here is your infinite empty musical space.”

Joseph Haydn: Die Schöpfung (The Creation), Hob.XXI:2 (Sunhae Im, soprano; Jan Kobow, tenor; Hanno Müller-Brachmann, bass-baritone; Christine Wehler, alto; Cologne Vocal Ensemble; Capella Augustina; Andreas Spering, cond.)

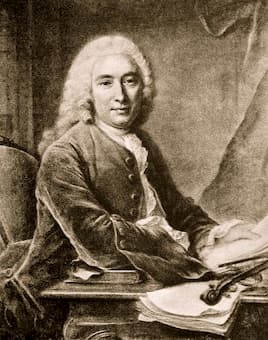

Portrait of Jean-Féry Rebel by Antoine Watteau, ca. 1710

Haydn’s setting of chaos and the creation myth gives clear testimony of his musical genius and of his unsurpassed imagination and originality. But not everybody was convinced, with a contemporary critic writing, “how the poet must have rejoiced as he put into the composer’s hand the idea of setting chaos to music; can there be a more unfortunate idea? All music is in itself order, rhythm. Without them no music is conceivable. A chaos of notes is no music but noise, shouting, racket and everything that lies beyond the sphere of the beautiful, the idealistic, is lost for art.” I suppose, that particular critic was unaware of the thunderous dissonances that open Les Élémens by Jean-Féry Rebel (1666-1747). It is undoubtedly the most shocking and original single measure of music composed up to that time.

La Création du Monde by Marc Chagall

Rebel’s foreword to the work gives us a glimpse of his thoughts: “The introduction to this work is Chaos itself; that confusion which reigned among the Elements before the moment when, subject to immutable laws, they assumed their prescribed places within the natural order. This initial idea led me somewhat further. I have dared to link the idea of the confusion of the Elements with that of confusion in Harmony. I have risked opening with all the notes sounding together, or rather, all the notes in an octave played as a single sound.” After all that chaos, in the subsequent Suite the bass expresses Earth, and the flutes imitate the flow and murmur of Water. Small flutes depict Air, and the violins represent the activity of Fire. Critics were unanimous, describing the work as “one of the most beautiful symphonic works in this genre.”

Jean-Féry Rebel: Les elemens, “Simphonie nouvelle” (Berlin Akademie für Alte Musik)

André Cardinal Destouches

The eleven-year old King Louis XV appeared in public at the Tuileries Palace in Paris on 24 February 1720. He wasn’t just greeting his humble subjects, but following the example set by Louis XIV—the one we know as “Le Roi Soleil”—he danced in the Ballet des élémens. Apparently, the young king did not enjoy the experience, and his performance did not meet with general appreciation. In fact, shy Louis would never again dance in another ballet. Les Élémens is a typical opéra-ballet with music composed by André Cardinal Destouches (1672-1749). In the prologue, Destiny makes the elements that replace chaos, but Venus is unhappy that she was not consulted. Destiny pacifies her by pointing to her future son, Louis XV. And in the following Dance divertissement, Louis XV appeared alongside twelve young noble courtiers. The four entrées—appropriately titled, Air, Water, Fire, and Earth—are musically and dramatically independent, but topically related to one another. Dramatically, as you might imagine, it’s all about love among the gods. The Epilogue once again saw the king on stage as he now symbolized the Sun. He is now flanked by a ballerina and by four high noblemen representing the four continents.

André Cardinal Destouches: Les Élémens (Academy of Ancient Music; Christopher Hogwood, cond.)

Darius Milhaud, 1923

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) visited the United States for the first time in 1922. He was immediately fascinated by the dance music performed by Leo Reisman and his Orchestra in Boston. But it was Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra in New York, and the music of the Harlem dance halls that aroused his keen interest in American jazz. Milhaud returned to Paris with countless records he had purchased in Harlem, and some months later he set to work on a ballet project. The ballet references an African creation myth as it was described in Blaise Cendrar’s Anthologie nègre.

Darius Milhaud teamed up with cubist artist Fernand Léger and author Blaise Cendrars for La Création du Monde

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Thank you. A very interesting and touching number especially in view of the tragic events around the world.