Only one of Engelbert Humperdinck’s compositions may have entered the repertoire, but what a composition it is! Today we’re looking at the life and work of Engelbert Humperdinck, composer of the magical fairy tale opera “Hansel und Gretel.”

Engelbert Humperdinck’s Childhood and Student Days

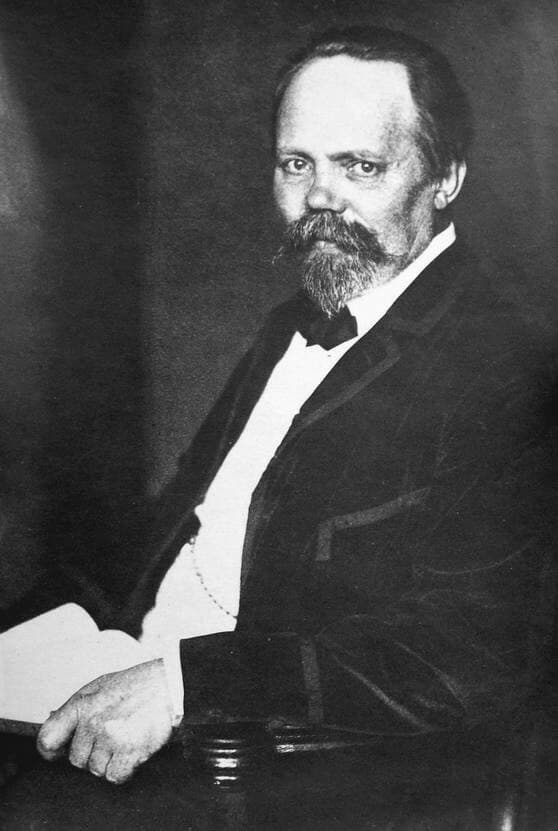

Engelbert Humperdinck

Engelbert Humperdinck was born in Siegburg, Germany, in 1854, to a high school teacher and the daughter of a cantor.

He started piano lessons as a child and wrote his first piece of music when he was seven, but his parents discouraged him from a musical career.

He ignored their wishes. In 1872, at eighteen, he began taking classes at the Cologne Conservatory, and in 1876, he began studying in Munich.

Engelbert Humperdinck: Violin Sonata (Thomas Probst, violin; Elenora Pertz, piano)

His hard work and belief in himself paid off in 1879, when he was in the first-ever class of Mendelssohn Award winners. Before the Nazis dismantled it in the 1930s, the Mendelssohn Award was a prestigious prize of 1500 marks granted to promising young composers or performers, funded by the Mendelssohn family.

Humperdinck chose to use his prize money to travel to Italy. The investment quickly paid off, because he met none other than Richard Wagner in Naples. In 1880, Wagner extended a career-making invitation to Humperdinck to come to Bayreuth to help work on the production of “Parsifal.” Humperdinck also helped teach music to Wagner’s son Siegfried, who went on to become a composer himself.

Humperdinck’s life in the 1880s was a nomadic one as he pursued teaching opportunities around Europe, including in Barcelona and Frankfurt. He was yet to compose a work that would make a splash.

The Story of “Hansel und Gretel”

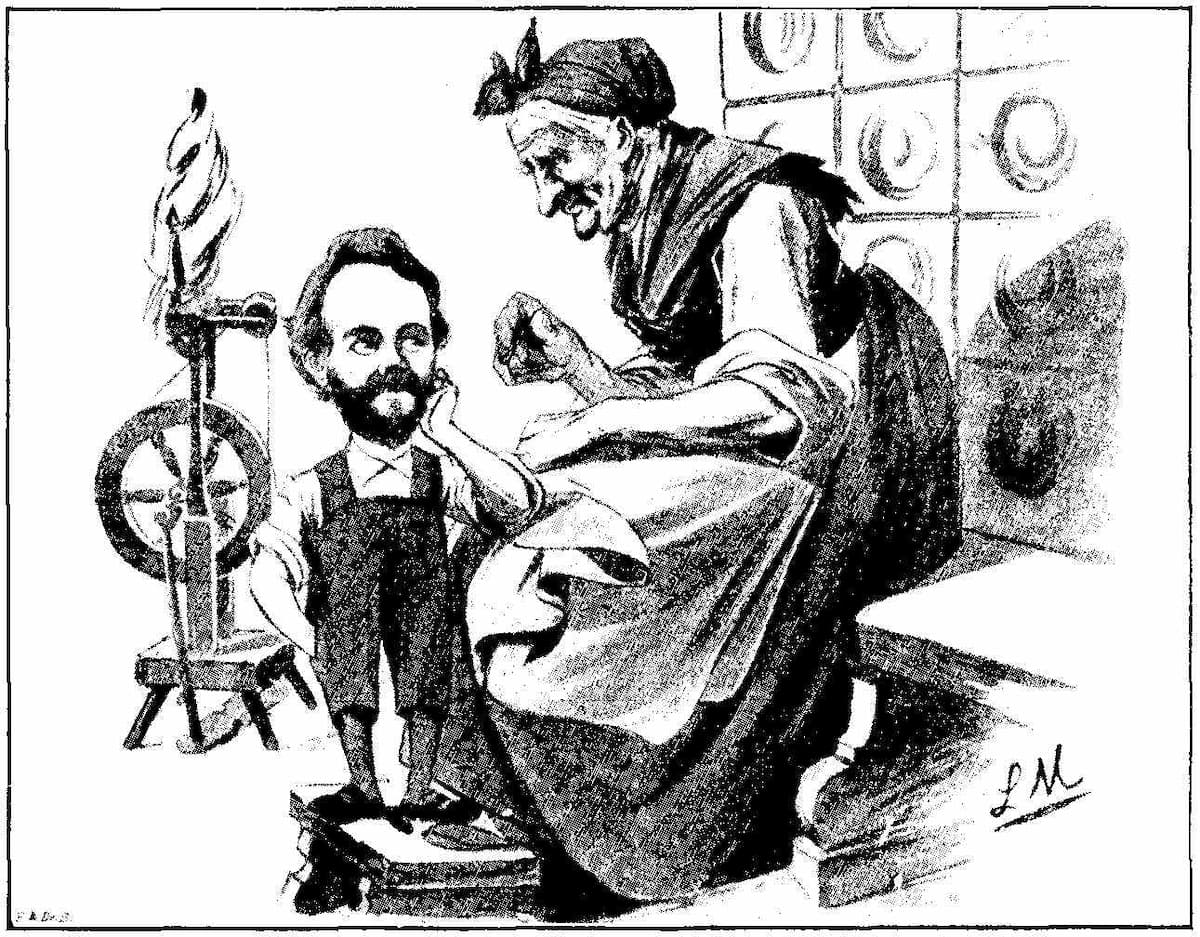

Engelbert Humperdinck and the storyteller

In 1890 his poet sister Adelheid wrote a fateful letter to Engelbert. She told him she had written a play based on the folktale of Hansel and Gretel, and asked him to set five of her verses from her manuscript to music.

The siblings collaborated on portions of the songs, and eventually Engelbert turned the project into a full-blown opera. “Hansel und Gretel” was premiered in Weimar in December 1893, with composer Richard Strauss conducting.

“Hansel und Gretel” was a massive overnight success. Within a year of its premiere, in Germany alone, fifty opera houses put on a production of it. In Hamburg, a young conductor named Gustav Mahler gave the Hamburg premiere. When it came to Vienna, Brahms was in the audience. The music world couldn’t stop talking about “Hansel und Gretel.”

Engelbert Humperdinck: Hansel und Gretel – Overture (Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Georg Solti, cond.)

The overnight success didn’t change his personality, though. One of Humperdinck’s friends wrote, “Dizzying world success and an excess of recognition have not changed Humperdinck: he remains the same balanced, modest, proper, kind, humorous and loving person, who – like his intellectual and poetic wife Hedwig – valued a simple, private family life and cultivated many hearty friendships this side of the border and beyond.”

After the career boost of “Hansel and Gretel”, Humperdinck taught in the resort town of Boppard and the capital city of Berlin. His students included up-and-coming composers like Kurt Weill and Hans Pfitzner.

Engelbert Humperdinck: Die Heirat wider Willen – Overture (Bamberg Symphony Orchestra; Karl Anton Rickenbacher, cond.)

A Comeback with Königskinder

Over the following years, he wrote more stage works, hoping to capture the success he’d enjoyed with “Hansel und Gretel.”

The most promising project was a Märchenoper – or fairy tale opera – called “Königskinder”, or King’s Children, which featured a technical and artistic innovation: a line delivery method that was halfway between singing and speaking. Eventually the story was turned into an all-out opera. At the American premiere, Geraldine Farrar – the star who popularized Madame Butterfly – made a huge impression as the main character, and even trained live geese to perform onstage with her.

But “Königskinder” was never as popular as “Hansel and Gretel”, possibly because of the war.

Aria from Engelbert Humperdinck’s Königskinder sung by Olga Kulchynska | Dutch National Opera

Engelbert Humperdinck and World War I

In 1914, Humperdinck was about to make a major life change and depart Europe for Australia to become director of the Sydney Conservatory – but then World War I broke out, and politics prevented him from taking the position.

On 4 October 1914 a wartime manifesto was released that became known as the “Manifesto of the Ninety-Three.” The manifesto protested what it called Allied countries’ “lies and calumnies” about Germany and German culture. In addition, the signatories claimed that Germany never wanted war, but that it would “carry on this war to the end as a civilized nation, to whom the legacy of a Goethe, a Beethoven, and a Kant is just as sacred as its own hearths and homes.”

Dozens of scientific and cultural figures from German life signed the manifesto. (One notable figure who didn’t was Richard Strauss, who believed that statements about politics were inappropriate for artists to give. It also later came out that not every signatory had been aware of what he’d been signing.) Getting tied up with this manifesto didn’t help the reputation of Humperdinck or his music among Allied nations, especially the English speaking ones.

Engelbert Humperdinck’s Final Years

In addition, by this time, he was facing serious health issues. In 1912, he had a stroke that paralyzed his left hand. However, he continued composing, getting his son Wolfram’s help with notating, given his partial paralysis.

Wolfram Humperdinck became involved in the theater and directed a production of Weber’s “Der Freischütz” in September 1921. His proud father attended the first show, but tragically had a heart attack during the performance. The following day, Engelbert Humperdinck died.

Engelbert Humperdinck is ultimately remembered as a bit of a one-hit wonder from opera history. In fact, it’s possible that nowadays he’s more famous for being the inspiration behind crooner Arnold Dorsey’s stage name than he is for anything he ever wrote. That said, “Hansel und Gretel” continues to be a fixture in the repertoire, and for as long as it’s performed, we’ll remember the man who composed it.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter