With his masterworks La Mer and Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, Claude Debussy reshaped the landscape of orchestral music by emphasising atmosphere, colour, and subtle harmonic explorations. Yet surprisingly, his orchestral catalogue contains a lesser-known work that has eluded widespread recognition.

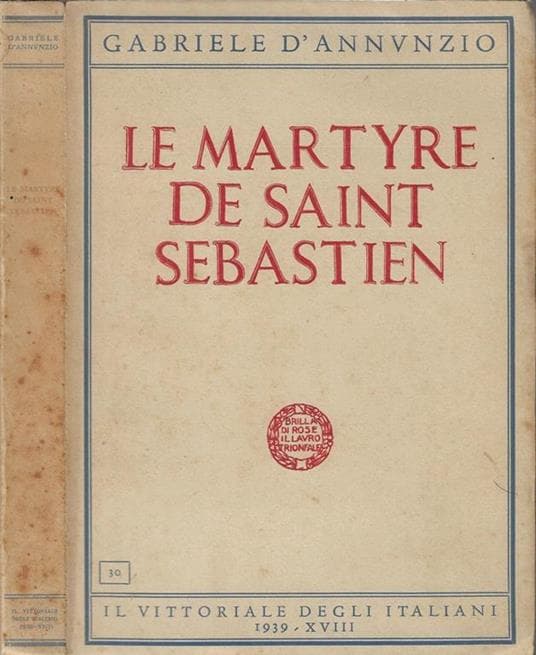

Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien

Originally, Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien, composed in 1911, was a sprawling and mystical oratorio. Blending lush impressionistic harmonies with a theatrical narrative drawn from Gabriele D’Annunzio’s poetic text, it is neither a full opera nor a concert piece. The original play, burdened by excessive length, overwrought text, and demanding performance requirements, has rarely been revived in full. However, assisted by his friend André Caplet, Debussy transformed the greater part of his incidental music into symphonic fragments.

For Debussy, this project held deep personal significance. Diagnosed with cancer during its composition, he may have found solace in its themes of transcendence and sacrifice. In a letter to Caplet, he wrote, “This music is for beyond the grave; it has no need of applause.”

Claude Debussy: Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien, “Fragments symphoniques” (La Cour de Lys) (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Esa-Pekka Salonen, cond.)

Background

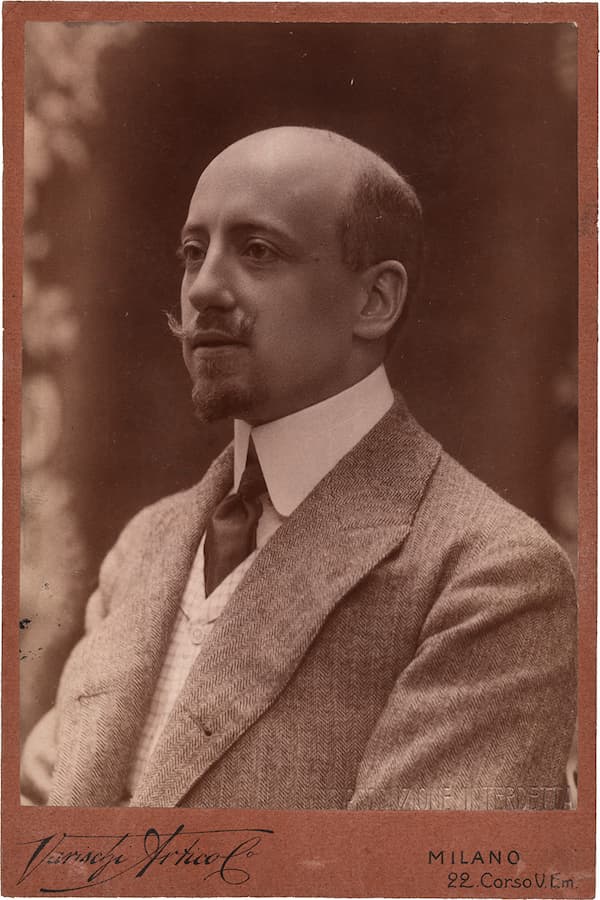

Gabriele D’Annunzio

Debussy embarked on a tour to Vienna and Budapest during the late autumn of 1910. He received a letter from the Italian writer Gabriele D’Annunzio asking him if he would compose music for his mystery play Le Martyre de saint Sébastien, with the danced role of the martyred saint assigned to Ida Rubinstein.

Although an established figure in the world of music, Debussy faced mounting financial difficulties and was looking to explore new and creative avenues. The commission came at this pivotal moment, offering financial rewards and a chance to engage with a grandiose and multidisciplinary project.

As Jacques Durand recalled, “The mystical subject suited Debussy’s rather introverted aesthetic. He also had personal ideas about the Passion mimed by Saint Sebastian in the mystery in question, ideas he explained to me and which were marked by a profound originality.”

Claude Debussy’s caricature, 1912

However, the project was not without controversy. The Catholic Church, alarmed by D’Annunzio’s decadent and sensual interpretation of a sacred subject, issued a condemnation of the play, placing it on the “Index of Forbidden Books.” Debussy, a lapsed Catholic had a rather complex relationship to religion, and he found himself navigating a rather delicate balance.

Claude Debussy: Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien, “Fragments symphoniques” (Danse extatique et Final du 1er Acte) (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Esa-Pekka Salonen, cond.)

The Premiere

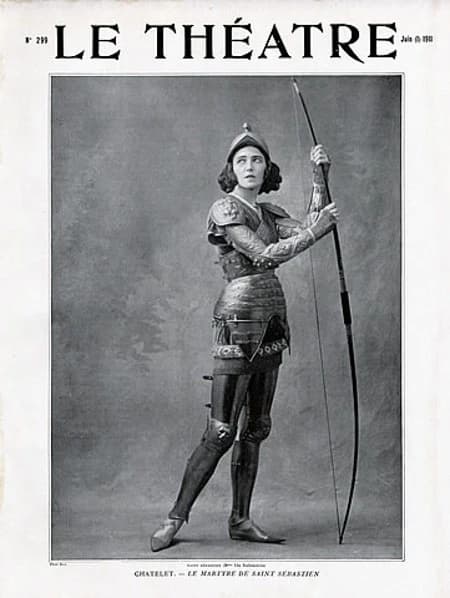

Debussy’s Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien costume

The flamboyant poet and dramatist Gabriele D’Annunzio had written the play as a lavish celebration of Catholic mysticism, inspired by the legend of Saint Sebastian. It tells the story of a Roman soldier martyred for his Christian faith under Emperor Diocletian. The play is divided into five acts, each corresponding to a phase of Sebastian’s journey.

The collaboration between Debussy and Annunzio appears to have been harmonious. Debussy later wrote, “I think I can say that it is one of my best and strongest memories.” It all premiered on 22 May 1911 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, with Ida Rubinstein in the titular role, choreography by Michel Fokine, designs by Léon Bakst, all under the baton of conductor André Caplet.

The reception was decidedly lukewarm. The extreme length of the performance, lasting close to five hours, taxed the attention span of the audience, while some objected to the “distortion of the story of one of our most glorious martyrs in the most unseemly manner.”

Debussy’s music was nonetheless praised. In all, it consisted of eighteen numbers lasting just under an hour in total. The critic Alfred Bruneau wrote in Le Matin, “each act contains superbly constructed instrumental ensembles that are full of striking and curious effects. The wild howls of the crowd are opposed by melodies of singular purity, hieratic, fantastic, religious and voluptuous preludes, dazzling fanfares, and lively dances complete this score, whose worth I am pleased to note.”

Claude Debussy: Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien, “Fragments symphoniques” (La Passion) (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Esa-Pekka Salonen, cond.)

Fragments symphoniques

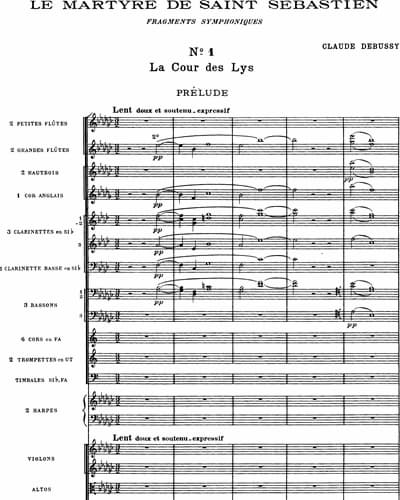

Claude Debussy’s Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien – Prelude

For reasons detailed above, Debussy transformed the greater part of his incidental music into “symphonic fragments” in 1912. He removed all the choruses and other selected passages. Debussy was already feeling the effects of his terminal illness, and Caplet offered his help with orchestration. In the event, these fragments transcend their functional origins and derive moments of transparency and radiance.

Debussy’s musical language is infused with a distinctive spiritual resonance. His use of modality, whole-tone harmonies, and parallel chords creates a sense of timelessness and ambiguity, evoking the sacred without adhering to traditional liturgical forms. The orchestration is luminous and transparent, and the prominent roles for harps, flutes, and celesta lend an angelic quality to the soundscape.

One of the score’s most striking features is its economy of means. Debussy avoids bombast, even in the climactic martyrdom scene, opting instead for understated intensity. This restraint amplifies the emotional impact, aligning with Debussy’s maxim that “music is the silence between the notes.” The luminous textures and innovative harmonies also prefigure Debussy’s final works, with Le Martyre serving as a creative bridge in his late career.

The symphonic fragments initially received a mixed reaction. Some critics, praising the “mystical poetry and luminous delicacy,” saw it as a distillation of his genius. Others found them disjointed and lamented the loss of a narrative thread. Critical debates notwithstanding, the fragments did gain traction in the concert hall, particularly after Debussy’s death. They bridge his impressionistic past with the modernist future, and their relative obscurity in relation to his major works only enhances their mystique.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Claude Debussy: Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien, “Fragments symphoniques” (Le Bon Pasteur) (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Esa-Pekka Salonen, cond.)