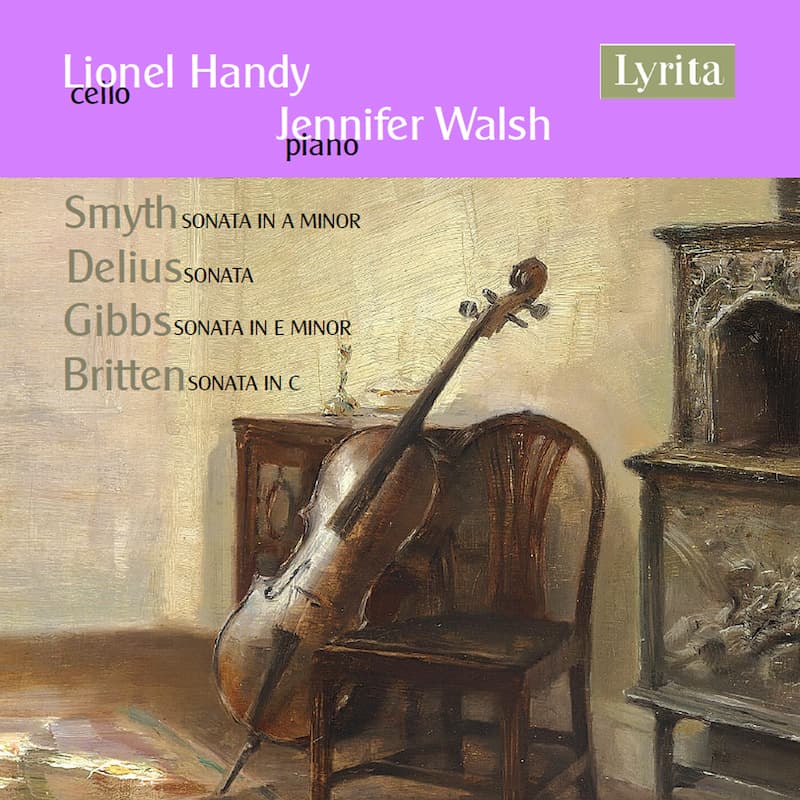

What do composers Ethel Smyth, Frederick Delius, Cecil Armstrong Gibbs, and Benjamin Britten have in common? If you guessed they all wrote cello sonatas, you’d be correct.

Cellist Lionel Handy and pianist Jennifer Walsh have brought these interesting British works to our attention in a new CD released on the label Lyrita on February 3rd, 2023. It follows their previous release of British Works volume I.

The composer and author Ethel Smyth, (1858-1944) unusually enough, achieved recognition during her lifetime. The Smyth Cello Sonata is dedicated to the esteemed German cellist Julius Klengel, whom we cellists know well from his etudes. The Sonata in A minor Op. 5, shows off the two instruments as partners and the vast expressive capabilities of the cello. Deep sonorities, massive in scope, and with three contrasting movements—an Allegro Moderato, a reflective Adagio non troppo, and a rhythmic Allegro Vivace—takes us through a breadth of moods and colors, which the cello renders so beautifully.

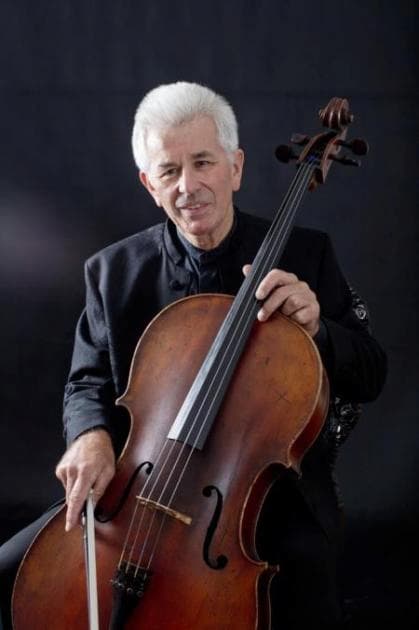

Lionel Handy

The opening is immediately captivating and Handy and Walsh begin dramatically. There is an urgency to the playing highlighting the poignant moods as the movement vacillates between the minor and major keys. Smyth features one instrument then the other, so the cello is never covered. The piano begins alone at the opening of the adagio. When Handy enters it is with a lovely tone. The movement is touching and fades away with melancholy. Beginning scherzo-like, the last movement moves from a propulsive and mysterious mood and often returns to melodic phrases. Handy and Walsh bring out the impulsive character of this movement.

Ethel Smyth: Cello Sonata in A Minor, Op. 5 – I. Allegro moderato

The Delius Sonata is a rhapsodic and lyrical work in one movement. Delius and his wife had fled from the encroaching German army in 1915 and they settled in London. There, Delius was introduced to Beatrice and May Harrison, the sisters who played cello and violin brilliantly. Delius wrote the cello sonata in 1916 for Beatrice who premiered the work in 1918. The duo brings out the moments of wistfulness in the Lento non troppo section and is especially lovely and flowing. The opening material returns, and it is full of leaps in the highest positions of the cello, not necessarily lying well on the instrument—perhaps the reason the work isn’t performed more often.

Cecil Armstrong Gibbs (1889-1960) a prolific British composer, is best known for his songs and choral music. The Cello Sonata in E Op 132 is from 1951, a three-movement work— Allegro molto, Lento, molto cantabile, “resting”, and “Broadly.” About twelve minutes in duration, it incorporates swings of tonality and wide dynamics. The beginning is in the dramatic lowest register of the cello with offbeats in the piano and there are moments of impressionism. The fullness of sound is lovely. The movement ends softly fading out and effectively leading to the lento, which remains wistful in mood, gentle and undulating. Movement three begins dramatically but soon becomes light-hearted with nimble repeated notes in the cello. The piece is performed with style and grace.

Cecil Armstrong Gibbs: Cello Sonata in E Major, Op. 132 – I. Allegro moderato

Cecil Armstrong Gibbs: Cello Sonata in E Major, Op. 132 – III. Broadly

Jennifer Walsh

Sorry to say I didn’t perform the Britten Cello Sonata in C major, Op. 65. It’s a brilliant and virtuosic work from 1961. Inspired by the playing of legendary cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, as were several cello works, Rostropovich said of the piece, “This is a sonata full of surprises, innovations for any cellist, gifts for the musician flowing freely from the horn of plenty. We meet not merely a novelty in finger-work but what is most important, a new kind of expressive [expression] and [a] profound dramatic composition.”

Covering a wide gamut of moods and techniques, it’s a work in five movements: ‘Dialogo’ Allegro, ‘Scherzo-pizzicato’ Allegretto, ‘Elegia’ Lento, ‘Marcia’ Energico, and ‘Moto Perpetuo’ Presto.

The opening is questioning, hesitating, with little interjections in the cello. It soon turns vivid going back and forth from restlessness to ferocity. The pizzicato movement is almost flirtatious, —the fast finger work in the piano, answered by plucking in the cello. The Elegia is a sudden contrast to the humor of the previous movement. Captivating and mournful and full of double notes in the cello, Handy and Walsh effectively portray the poetry of the Elegia playing expressively all the way to the ending sigh. The March is unexpected, sardonic, propulsive, with effects such as ponticello (played on the bridge for a raspy sound), harmonics (whistling sound), and tremolo (shimmering and fast repeated notes.) The movement ends quite abruptly with a glissando in the piano disappearing into nothingness—effectively executed by Handy and Walsh.

The Molto perpetuo finale, played ricoché in the cello—a musical term denoting using the bow to play very fast repeated notes by throwing or bouncing the bow to produce successive staccato notes, is not an easy technique to control. Both musicians perform the brisk repeated notes effortlessly, first softly and then building to aggressive strokes, and eventually to a unison that takes our breath away as the piece concludes. Handy and Walsh play this work with conviction and flair. The Britten Cello Sonata, a tremendous piece, deserves wider performance.

Benjamin Britten: Cello Sonata in C Major, Op. 65 – III. Elegia. Lento

Benjamin Britten: Cello Sonata in C Major, Op. 65 – V. Moto Perpetuo. Presto

British Cello Works-volume 2 is a welcome addition to the oeuvre. The two longer works, the Smyth and Britten, bookending the album in a satisfying way, showcase uncommon but noteworthy repertoire for the cello.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter