Britten and Pears in Bali

Benjamin Britten was working on the full-length ballet The Prince of the Pagodas when he wrote to Edith Sitwell that he was “on the threshold of a new musical world.” This project, slated for Covent Garden, was set aside for an extensive tour with Peter Pears from November 1955 to March 1956. They primarily traveled throughout Asia, initially seeking out indigenous traditional dances, music and dramas of Japan. Traveling through Indonesia, Britten conducted a more detailed study of local musical styles in Java and in Bali, and he excitedly wrote, “fantastically rich—melodically, rhythmically, texture and above all formally… At last I’m beginning to catch on to the technique, but it’s about as complicated as Schönberg.” For one, the visit to Bali provided a more literal reference to the gamelan in The Prince of the Pagodas. However, the Asian excursion also spawned a fascinating setting of Chinese poetry.

Benjamin Britten: Songs from the Chinese (Ivonne Fuchs, alto; Georg Gulyas, guitar)

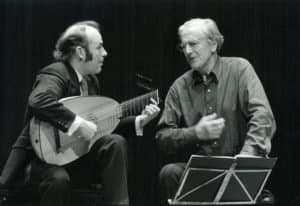

Julian Bream and Peter Pears

The song cycle Songs from the Chinese was composed during the autumn of 1957. It consists of six poems translated from the original Chinese by the Orientalist and Sinologist Arthur Waley. Waley was called the ambassador from East to West in the first half of the 20th century, “the great transmitter of the high literary cultures of China and Japan to the English-reading general public.” Uniquely, this cycle is scored for tenor and guitar as the result of Britten’s friendship with the guitarist Julian Bream. In his setting, Britten makes no particular attempt to evoke a Chinese atmosphere, but focuses on the transient nature of beauty and youth espoused in the poetry. In fact, the themes of innocence, loss and regret are common tropes in his artistic imagination. In 1959, the critic Jeremy Noble rather enthusiastically wrote, “as a whole, they make a statement about life (and particularly the transience of youth and beauty) as poignant and personal as Mahler‘s own settings from the Chinese.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter