Manuel María Ponce (1882-1948), the leading Mexican musician of his time, was a wonderful pianist who composed a substantial number of piano works. These works combine a profound knowledge of the instrument with his Romantic heritage and nationalist tendencies.

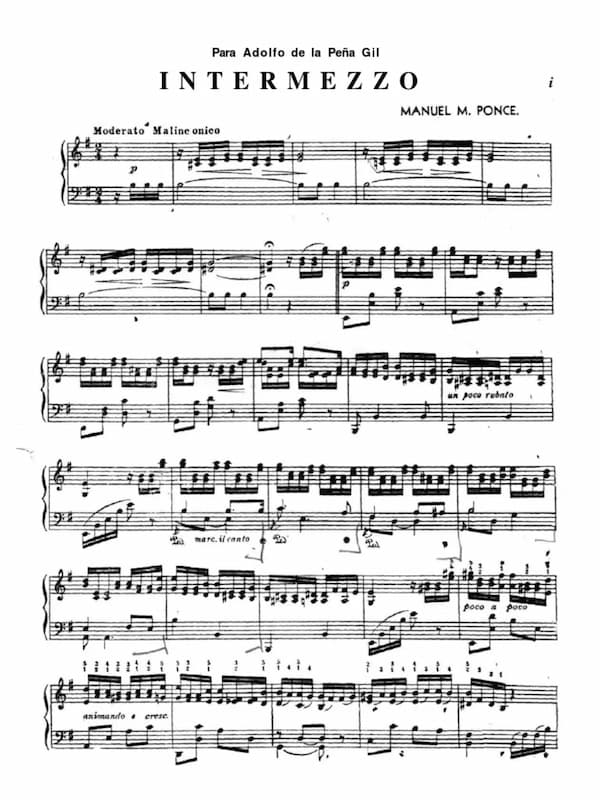

Manuel Ponce: Intermezzo No. 1 in E minor

As Ricardo Miranda Pérez wrote, “his works display a happy combination of Lisztian virtuosity, Romantic genre and popular Mexican tunes or melodic turns of phrase inspired by Mexican songs.” We thought it might be fun to explore Manuel María Ponce at the piano, won’t you join us?

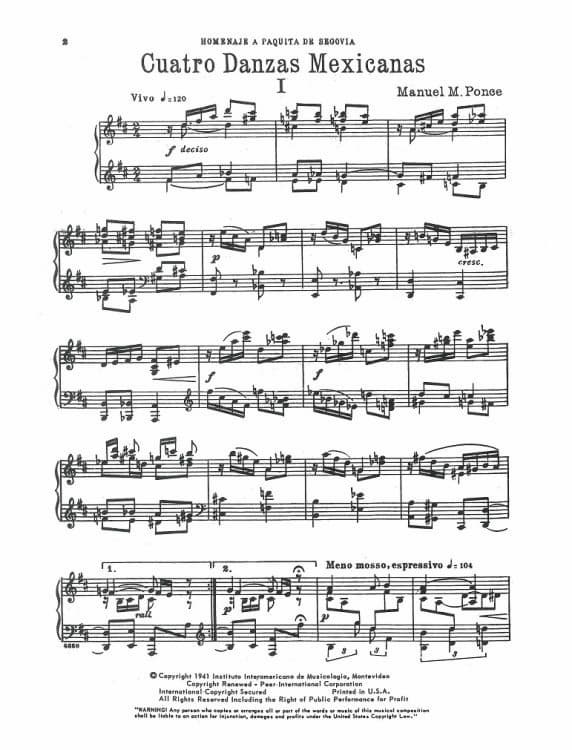

Manuel Ponce: 4 Danzas mexicanas (Álvaro Cendoya, piano)

Prodigy

Manuel María Ponce

It was evident from an early age that Manuel Ponce was a musical prodigy. His older sister Josefina noticed that her brother sat in front of the instrument and immediately played back the pieces he had heard. Formal piano lessons soon followed, and by the age of fifteen, he was appointed titular organist in the Church of San Diego.

Looking to expand his horizons, Ponce studied in Mexico City at the Conservatorio Nacional with Vicente Mañas (piano) and Eduardo Gabrielli (harmony). At that time, Ponce had a substantial number of compositions to his name, primarily smaller in form, such as the Mazurka, Gavotte, and Danza. As he felt that there was nothing to be learned at the Conservatorio, he decided to move to Aguascalientes and earned a living giving music lessons.

Manuel Ponce: Mazurca de salón No. 6 in G Major (Arturo Nieto-Dorantes, piano)

Italy

Manuel Ponce’s 4 Danzas Mexicanas – No. 1 music score

At the age of 23, his former teacher Eduardo Gabrielli encouraged Ponce to continue his studies in Europe, and he introduced him to Marco Enrico Bossi, director of the Liceo Musicale in Bologna. Ponce arrived in 1904 with the intention of studying composition, and Bossi introduced him to Cesare Dall’Olio, a teacher of Puccini.

During his time in Bologna, Ponce made friends with Luigi Torchi, an imminent musicologist who had studied with Salomon Jadasson and Carl Reinecke in Leipzig. He devoted himself to the study of literature in Italy, and he was a librarian at the Liceo Musicale Rossini in Pesaro. Ponce became an avid musicologist and, subsequently, a devoted collector of traditional Mexican folksongs.

Manuel Ponce: Piano Sonata No. 1 (Arturo Nieto-Dorantes, piano)

Berlin

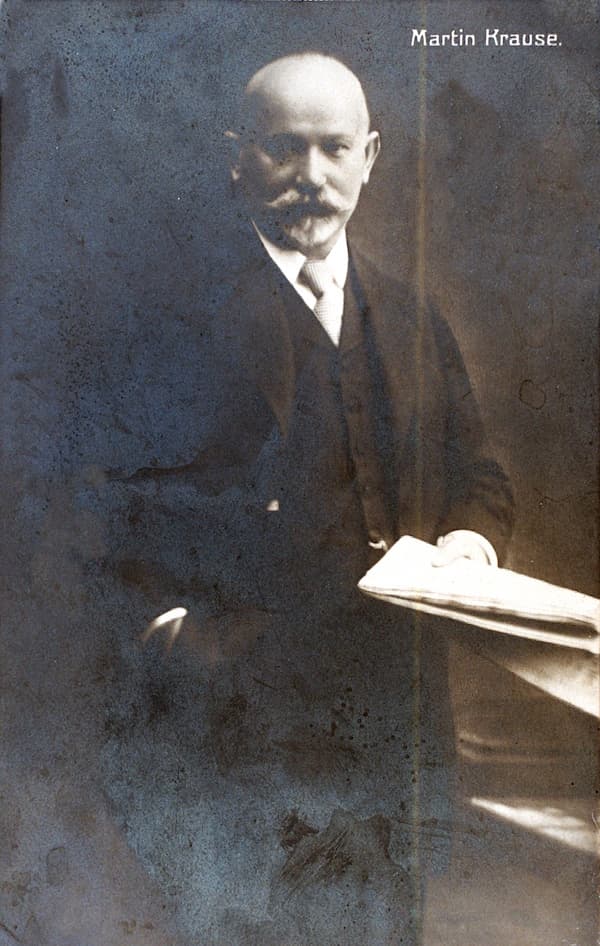

Martin Krause

During his time in Bologna, Ponce composed the opening movements of his Trio for piano, violin, and viola, alongside the first Piano Sonata, and four Mazurkas. When Dall’Olio died in December 1905, Ponce decided to move to Germany, and he enrolled in the class of Martin Krause at the Stern Conservatoire in Berlin.

Krause had been a student of Franz Liszt, and he later became one of Liszt’s most prominent promoters. He established himself as a piano teacher and writer on music and was one of the founders of the Franz-Liszt-Verein. The immediate result of Ponce’s studies in Germany was the composition of a number of concert studies that explore instrumental virtuosity inspired by Liszt. Ponce even added an evocative epigraph to the head of his scores, suggesting the atmosphere to be conjured in each study.

Manuel Ponce: 12 Concert Studies – No. 1 Tragic Prelude (Álvaro Cendoya, piano)

Manuel Ponce: 12 Concert Studies – No. 3 Towards the Summit (Álvaro Cendoya, piano)

Return to Mexico

Manuel Ponce

Financial considerations forced Ponce to return to Mexico in 1908. He privately taught piano to make a living and, by the end of that year, moved to Mexico City to take up a post teaching piano at the Conservatorio Nacional. He also conducted research and fieldwork into his own musical heritage, which decidedly contributed to the development of a Mexican national style.

Ponce would embrace that style in his impressionist and later neo-classical compositions. For the 1910 centenary celebration of Mexican independence, Ponce organised a prestigious panel of judges that included Pedrell, Fauré and Saint-Saëns for a composing competition. Ponce took over the professorship at the Conservatorio, and in 1911, he composed his first large work, the Piano Concerto.

Manuel Ponce: Piano Concerto No. 1, “Romantico”

“La musica y la canción Mexicana”

Manuel Ponce’s Intermezzo music score

The “Romantic” Piano Concerto confirmed Ponce as the most important figure in Mexican music at the time, and he composed a number of works with national themes, such as the “Balada Mexicana,” “Arulladora Mexicana,” and “Barcarola Mexicana.” He also fashioned several arrangements of Mexican folk ballads for voice and piano.

His first lecture, “Music and the Mexican Song”, in 1913, immediately caused a stir. Ponce strongly advocated the rise of a national musical consciousness and called for a new evaluation of folklore. The lecture was immediately published and widely discussed, and it formed the catalyst for the so-called “Mexican nationalist School.”

Manuel Ponce: Barcarola Mexicana “Xochimilco” (Álvaro Cendoya, piano)

Havana

Heitor Villa-Lobos (1922)

Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887–1959) met Ponce in Paris in the 1920s. He remembers, “I asked him at that time if the composers of his country were as yet taking an interest in native music, and he answered that he himself had been working in that direction. It gave me great joy to learn that in that distant part of my continent, there was another artist who was arming himself with the resources of the folklore of his people in the struggle for the future musical independence of his country.”

Musical independence, however, had to wait for political and social difficulties to be sorted. The Mexican Revolution forced Ponce to vacate the country from 1915 to 1917. Like many other Mexican artists and intellectuals, Ponce went to Havana, where he played concerts and gave lectures and classes while writing music reviews.

Manuel Ponce: Suite Cubana (Álvaro Cendoya, piano)

Paris

Conductor Lamberto Baldi, Manuel M. Ponce and Andrés Segovia

When Manuel Ponce returned to Mexico, he took up his post at the conservatory again. He conducted a number of performances by the National Symphony Orchestra, which invited soloists such as Rubinstein and Casals, and numerous Mexican premières. Ponce also got involved in various publishing projects, including the establishment of the magazine Revista musical de México.

Looking to refresh his compositional palate and being conscious of the rapid musical transformations taking place at the time, Ponce returned to Europe and settled in Paris in 1925. He studied with Dukas until 1933 and reconnected with guitarist Andre Segovia, with whom he remained friends until his death. That friendship was indeed groundbreaking, and most of his guitar pieces were written during his time in Paris.

Manuel Ponce: Moderato Malinconico (Álvaro Cendoya, piano)

Mexico

By 1933, Ponce returned to Mexico to concentrate on teaching and composing. He was appointed director of the National Conservatory that year, and he founded the chair in folklore at the National School of Music in 1934. As a scholar writes, “Ponce was a prolific writer, and he published numerous articles and features on musical topics ranging from piano technique to issues surrounding the media.”

The didactic aspect of Ponce’s career is beautifully expressed in his “Twenty Easy Pieces” of 1939. Each piece presents specific characteristics—expressive, stylistic, compositional or pianistic—in the context of brief reminiscences of various historical moments in his country’s history.

Manuel Ponce: 20 Easy Pieces (Álvaro Cendoya, piano)

Premio Nacional de Artes

Manuel Ponce

Ponce gave many important premières and performances of his works in the 1930s and 40s. His Chapultepec with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Stokowski premiered in 1934, the Suite en estilo antiguo in 1935, Merlín in 1938, and the Violin Concerto with Szeryng in 1943. Ponce received countless prizes and distinctions, including the prestigious “Premio Nacional de Arts” in 1947.

While Ponce’s reputation rests primarily on his guitar works, he crafted over 400 compositions for the piano. He left behind a wealth of works for his most beloved instruments, ranging from salon dances to learned fugues. His musical voice emerged from a combination of Musical Romanticism, French Impressionism, Neoclassical models, and Mexican folk songs. To be sure, Ponce saw himself first and foremost as a composer of the piano.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter