In his 2016-2017 collection, George Crumb metamorphosed art by 8 artists into 10 piano works. These weren’t music representations of the actions in the pictures, such as what was done in the past with tone poems, but a far more subtle process of ‘transmuting sight into sound’. Think of these as parts of a gallery of art and music.

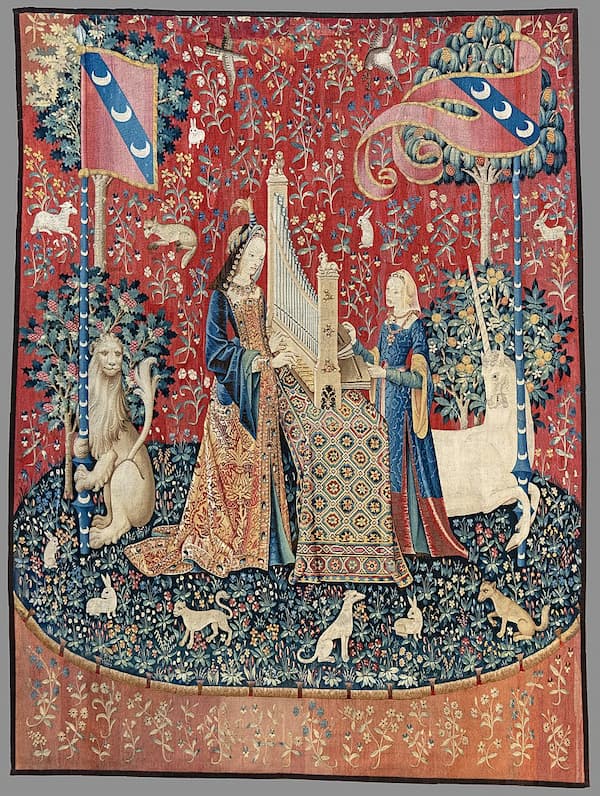

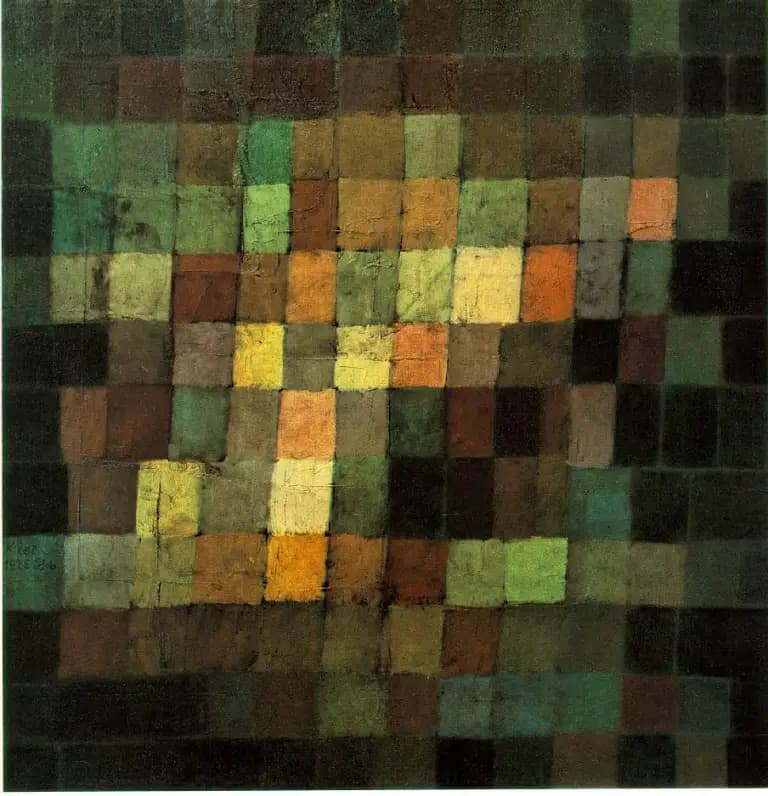

Crumb’s Metamorphoses, Book II (2018–2020) starts with the same artist as Book I: Paul Klee. The two paintings Crumb uses are only two years apart in creation (1925 and 1923) but two styles apart in style. In Ancient Sound, Abstract on Black (1925), Klee started first with an all-black canvas, divided his field into 13 x 12 squares, and juxtaposed colours, reserving his brighter colours (yellow, orange, light green) for the squares in the middle. The squares are not uniform in size, but smaller towards the middle. The patina speaks to the age-old rose, faded colours, and all kinds of browns and greys. The whole work is a shift of shades and shadows, lights and darks. Despite the seeming static image, we seem to sense movement in it.

Paul Klee: Alter Klang: Abstrakt auf Schwarz (Ancient Sound: Abstract on Black, 1925)

Crumb takes his cue from the title and with the use of perfect fourths, invokes the sound of medieval organum tied with an inversion of the usual perfect fifth drone common in folk music. By holding down the sostenuto pedal, the pianist has 7 notes (not the usual 2) providing the drone while the perfect fourth melody tracks up and down above it. At the same time, the pianist plays glissandos on the strings with his thumbnail. The flicks of treble colour seem to have the same effect as Klee’s use of brighter colours.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 2 – No. 1. Ancient Sound, Abstract on Black (after painting by Paul Klee, 1925) (Marcantonio Barone, piano)

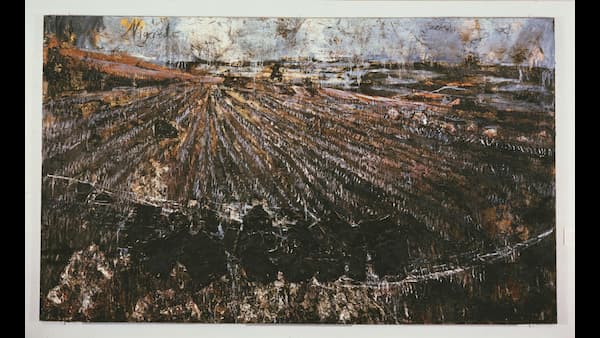

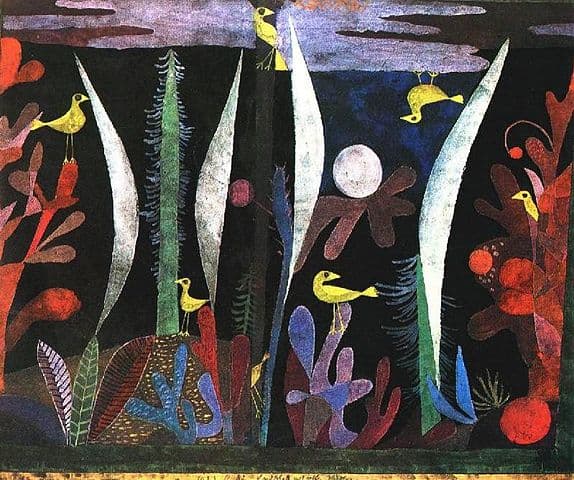

Klee takes 7 yellow birds and places them in a fantastic forest, bright against a black background. We move in a dream-like setting, chasing the same kinds of shades and shadows, lights and darks we had in Alter Klang, and, like Alter Klang, a black background is behind it all. The birds are in all positions: hiding, holding upside down to clouds, peering back over their shoulders, or just standing there on two feet.

Paul Klee: Landscape with Yellow Birds, 1923

Crumb catches the sound of the birds in his twitters on the higher keys and captures the dark background through the open lower strings and string scrapes. We’re moving into the black at the back of the image while at the same time, the sound of the birds brings us back. By using the sustain pedal, the echo in the piano gives the dark background and the right-hand twitters are always birds.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 2 – No. 2. Landscape with Yellow Birds (after painting by Paul Klee, 1923) (Marcantonio Barone, piano)

One of the saddest and strongest images from the mid-20th century was Andrew Wyeth’s painting of his Maine neighbor Anna Christina Olson. From childhood she had been unable to walk but refused the aid of a wheelchair, dragging herself around with the strength of her arms. When you first see the painting, you see, perhaps, a woman in a field wearing a pink dress, looking up at the house on the hill above her. Perhaps there’s someone coming because there’s an expectancy in her position. As you learn more about the subject’s history, you realise that this isn’t a painting of a reality but of a psychological landscape. For Christina, everything is far away and up a hill and she can only get there through her own strength. It’s a difficult concept to bring to a painting but Wyeth brings forth her extraordinary strength of mind and body over reality.

Andrew Wyeth: Christina’s World, 1948 (MoMA)

The instructions given by Crumb are to play the piece ‘slowly, plaintively (like a broken idyll)’ while continuously holding down the damper pedal. The melody becomes introspective, scraping of the bass strings gives us subtle harmonics. It’s an unsettling portrait in the painting and in the music.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 2 – No. 3. Christina’s World (after painting by Andrew Wyeth, 1948) (Marcantonio Barone, piano)

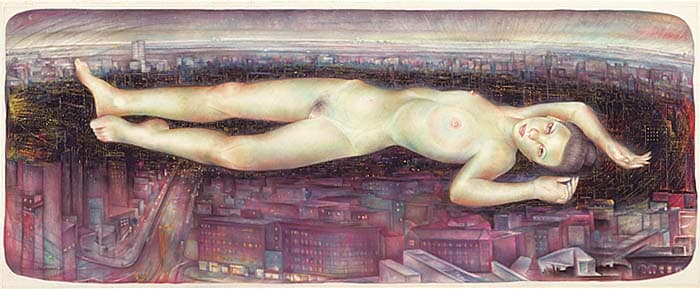

Purple Haze shows a naked woman floating above a purple Manhattan nightscape. It’s part of a collection of three paintings that show the same woman, in the same pose, on a bed (Dream Palace), and in a green setting (Wildflowers). As the world around her changes, so do our perceptions – we can think of Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe for a model of a naked woman in a green world and any number of images of a naked woman, such as Manet’s Olympia, on a bed, but naked woman taking over a city is far less common. What Dinnerstein’s image shares with Manet’s two ground-breaking images is the cool gaze of the woman at the viewer. She owns the scene and she owns you.

Simon Dinnerstein: Purple Haze, 1991

For musicians, the title Purple Haze may not invoke the city colours as much as Jimi Hendrix’ pop song of the same name. For Crumb, the inspiration was the painting, but he said that he also took a certain bluesy element from Hendrix’ work. The bass plays a constant two-bar pattern which is imitated in the right hand playing inside the piano before fading away…and coming back with a treble blast.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 2 – No. 4. Purple Haze (after painting by Simon Dinnerstein, 1991) (Marcantonio Barone, piano)

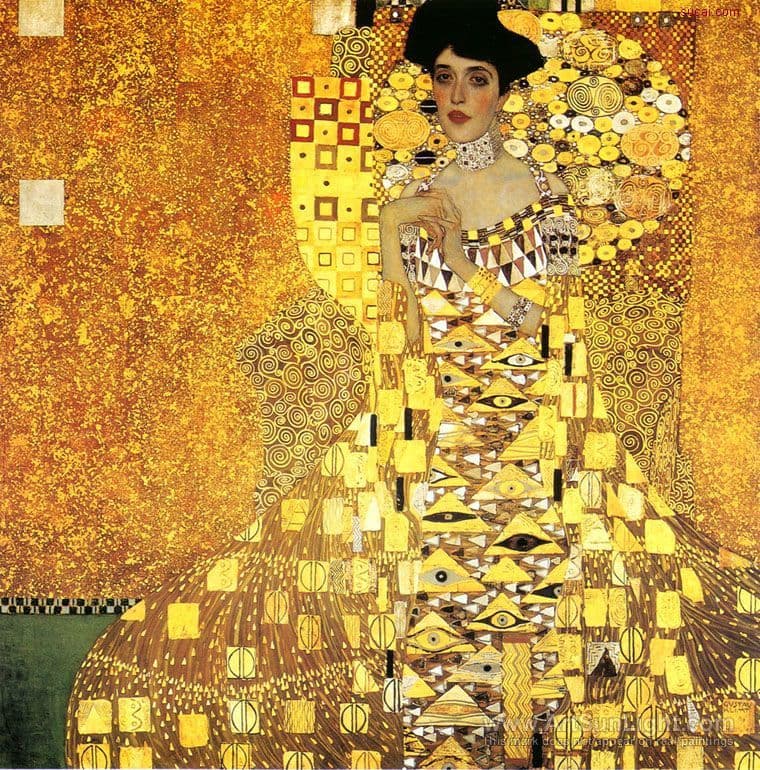

Gustav Klimt answered the commission by banker Ferdinand Block-Bauer for a portrait of his wife Adele with an extraordinary gold painting. Nearly life-size, 140 x 140 (4’5” x 4’5”), the painting is one of the greatest of Klimt’s gold period paintings. One of his inspirations for the work was the gold mosaic work at the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravena and it could be out there in the infinite number of small geometric patterns. Clad in a golden dress, sitting on a golden chair, surrounded by a gold and silver design, Adele Block-Bauer almost accidentally emerges from the background, One writer sees the work as a culmination of a world of painting: ‘the gold is like that in Byzantine mosaics; the eyes on the dress are Egyptian, the repeated coils and whorls Mycenaean, while other decorative devices, based on the initial letters of the sitter’s name, are vaguely Greek’. The total effect, however, is dazzling.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, 1907 (New York: Neue Galerie)

Crumb catches both the action of the painting and the inevitable stillness of any portrait. The music glistens and catches the light like Klimt’s portrait, each element ringing freely with the lifting of the damper pedal. Metal wind chimes add to the metallic sheen.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 2 – No. 5. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (Lady in Gold) (after painting by Gustav Klimt, 1907) (Marcantonio Barone, piano)

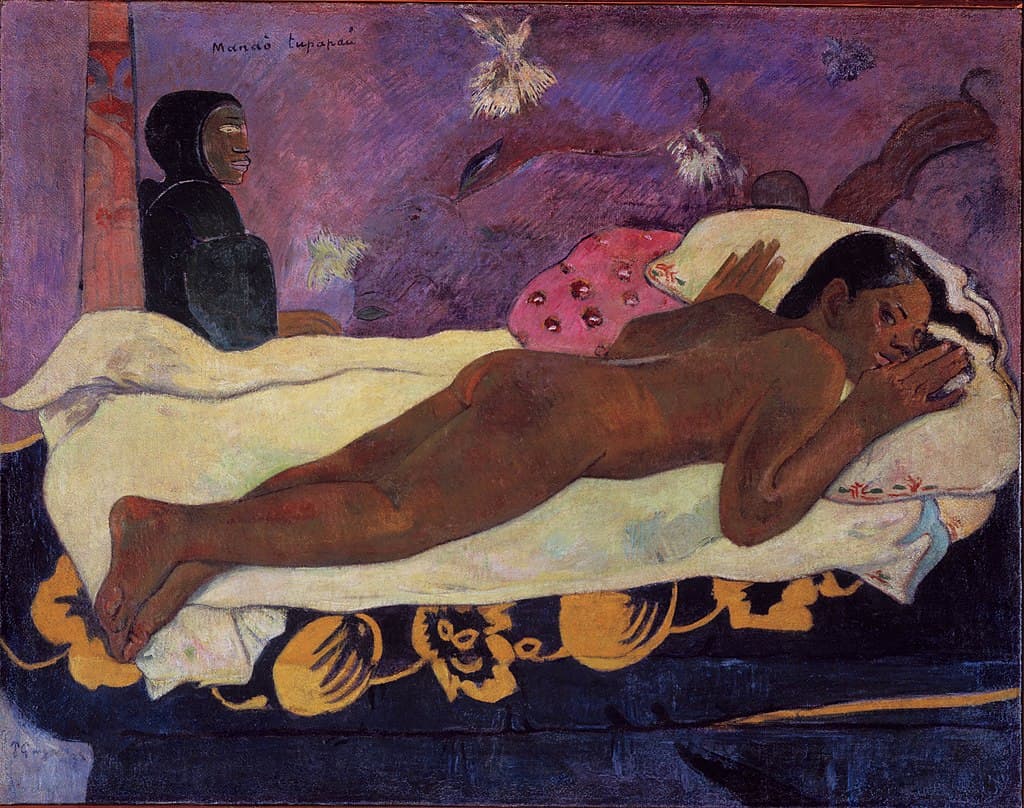

A nude in a different position, and also reclining on a bed, is at the centre of Gauguin’s Manao tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Keep Watch). Behind his model, Tahe’amana, Gauguin shows the shadows that she feared at night: the spirits of the dead who phosphoresce at night. He’s made the ghost a small old woman, the most familiar form of death to his model. The title of the work, as Gauguin noted to his daughter, went both ways: either the model is thinking of the ghost or the ghost thinks of her.

Paul Gauguin: Manao tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Keep Watch), 1892 (Buffalo, NY: Albright Knox Art Gallery)

The title of the painting, Manao tupapau, was used by Crumb in his music in Metamorphoses, Book I for the pianist to shout during ‘Contes barbes’ (Book I, No. 8). Crumb found Gauguin’s image disturbing and creates music that is dark and unsettled. He writes a ‘death drone’ in the bass, ‘an eerie rainbow of harmonic partials that are produced by continuous, rhythmic scraping motions along the metal winding of the low C-sharp string.’ Other sounds include strokes on a spring-coil drum and a sizzle cymbal. Hidden in the middle is Crumb’s own invocation to the ancient spirits: the notes B-flat – A – C – B natural summoning the spirit of the letters: B-A-C-H (in the German spelling of the notes).

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 2 – No. 6. Spirit of the Dead Watching (after painting by Paul Gauguin, 1892) (Marcantonio Barone, piano)

Considered the greatest anti-war painting, Pablo Picasso’s 1937 work Guernica represents the death of the city of Guernica at the hands of fascist forces from Germany and Italy. The picture is monumental, 26 feet long by 12 feet high (793 cm x 366 cm) and keeps the horrors to the forefront: a gored horse, a bull, screaming women, a dead baby, a soldier in pieces, and flames. Above it all, the sun stares down at this scene of distraction.

Picasso: Guernica, 1937 (Madrid: Museo Reina Sofia)

The crack of machine-gun fire opens Crumb’s Guernica. Metal rulers on the strings make a jangly sound as the keys are played. The pianist is instructed to play with violent force and the piece builds to a terrible climax, before collapsing from the highest to the lowest. At the end, the pianist quietly says ‘Guernica’ three times.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 2 – No. 1 No. 7. Guernica (after painting by Pablo Picasso, 1937) (Marcantonio Barone, piano)

Georgia O’Keeffe’s western paintings, filled with never-ending vistas and reminders of the life that lived there, here superimpose an impossible set of horns, a skull, and a long view vista with white-capped mountains. The sky is that of a sunset, the blue coming down to the horizon in a pink shower. The bones and horns were a symbol of the desert to O’Keeffe she said in 1939. This bony trash of the desert became a signature object for her. This isn’t a still-life painting, because no mule deer ever looked like this – one writer compared the mass of horns to a kind of western Medusa head. The landscape is distant and is seen from a high viewpoint. From that faraway place have come these ‘nearby’ horns.

O’Keeffe: From the Faraway, Nearby, 1937 (Metropolitan Museum)

Viewed 80 years later, the picture is seen by Crumb as a ‘profound lesson on the fragility of life’. The piano’s internal cross beam is hit with a mallet and maraca and bamboo windchimes summon the dry landscape. The work is in three sections, each of which ends with the pianist whispering the title of O’Keefe’s painting (From the Faraway, Nearby). It’s a light rhythmic piece, much in contrast with the piece that preceded it.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 2 – No. 8. From the Faraway, Nearby (after painting by Georgia O’Keeffe, 1937) (Marcantonio Barone, piano)

Marc Chagall’s Les Pâques (Easter), reflects Christian Easter in its title but Jewish Passover (La Pâque) in its imagery. The painting is filled with dramatic colour: the bottom is near black and white, with the complementary colours of red and green at the top of the frame. We are again in Chagall’s home village of Vitebsk, which we saw in Le violiniste of Crumb’s Book I, No. 4. There are the wooden houses, there are the villagers seated for the Passover feast, and a winged creature flies over the roof. The sun, in the centre, pours down a white icy light. The winged creature seems to block the red light from hitting the village and the villagers, protecting all from foreign danger. At the right, a horned animal’s head (a lamb, perhaps?) peers out on this astonishing scene. There are hints of colour on the houses, but the bright colours in the sky almost seem like stained glass windows, mediating light from a higher source – higher than even the sun.

Marc Chagall: Les Pâques, 1968 (private collection)

A march in the opening passage, played both inside and on the keys of the piano. Just as in Chagall’s painting, bright colours emerge from the darkness only to sink down again. A delicate melody is smashed by an explosive bass chord, once, twice, until it re-emerges to have the final say.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 2 – No. 9. Easter (after painting by Marc Chagall, 1968) (Marcantonio Barone, piano)

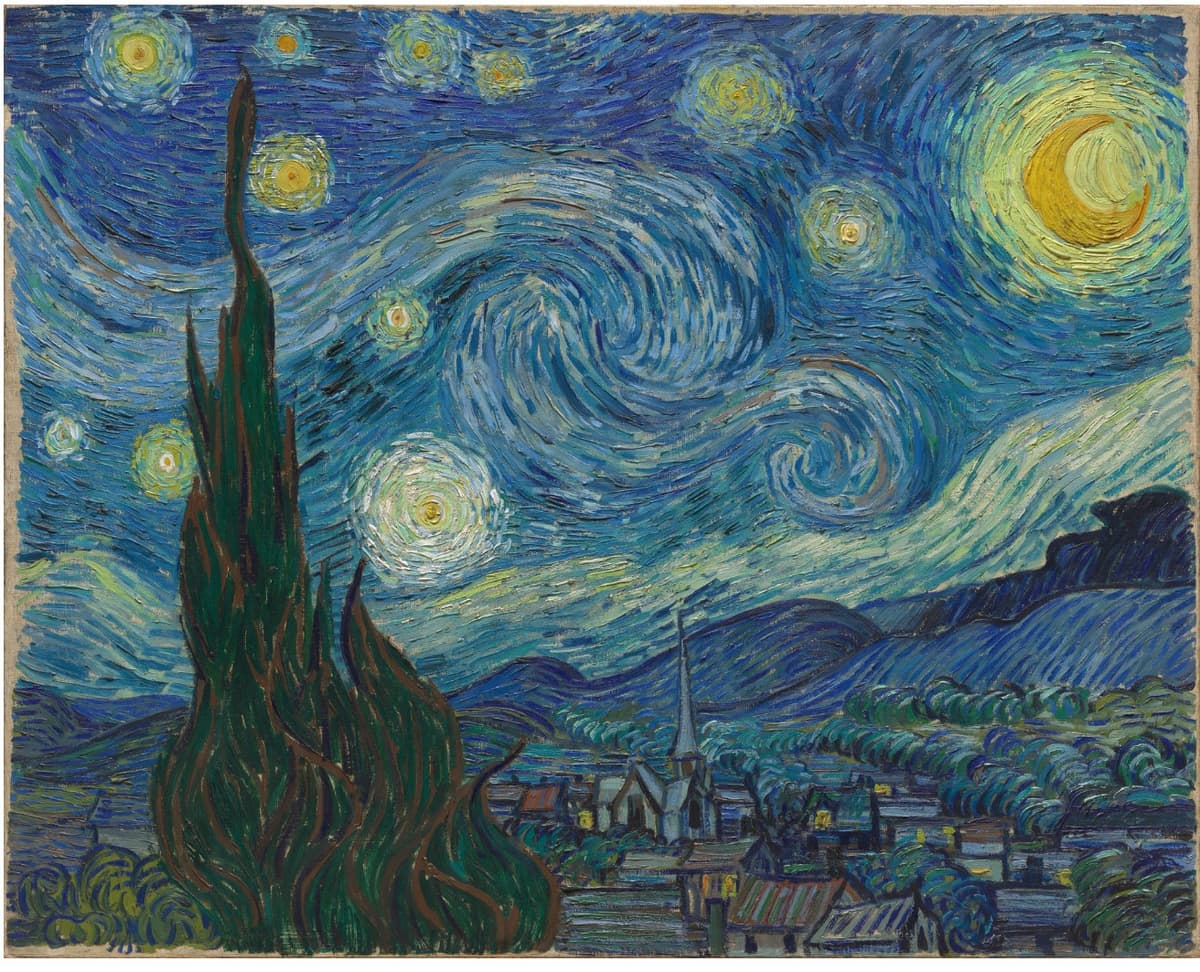

Peering out of the window of his asylum room, Vincent van Gogh captured the world at night. The quiet town sits, and above it, the heavens whirl in an uncanny display. The picture combines several perspectives: he could not see the town from his room, for example, and the sky seems close enough to touch. These are not the colours of night: the blues and yellows and whites, but in the hands of van Gogh and with the inspiration of the impressionists for seeing reality as painted many colours, this has become a night of glorious stars. A moon in the upper right glows yellow as the sun at its centre and, lower in the sky, Venus appears. Below it, the town sleeps, unaware of the explosion of life and colour above it.

Vincent van Gogh: The Starry Night, 1889 (MoMA)

Where the exuberant brushwork of van Gogh’s painting is viewed by some as indicative of his troubled mind, Crumb reads it as a quiet music, filled with ‘infinite calm’. Gentle lines, rising and falling at the opening, are the swirls across the sky, while the darkness at the foot of the painting becomes low bass figures. The stars are bright sounds picked out of the darkness until, at the end, it all blows away with the pianist’s light whistling, ghostly sounds in the moonlight.

George Crumb: Metamorphoses, Book 2 – No. 10. The Starry Night (after painting by Vincent van Gogh, 1889) (Marcantonio Barone, piano)

Although the themes of Metamorphoses Book II are darker than those of Book I, the second collection, with the light and fleeting sound of the ending, leaves us ensorcelled in Crumb’s own musical magic.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter