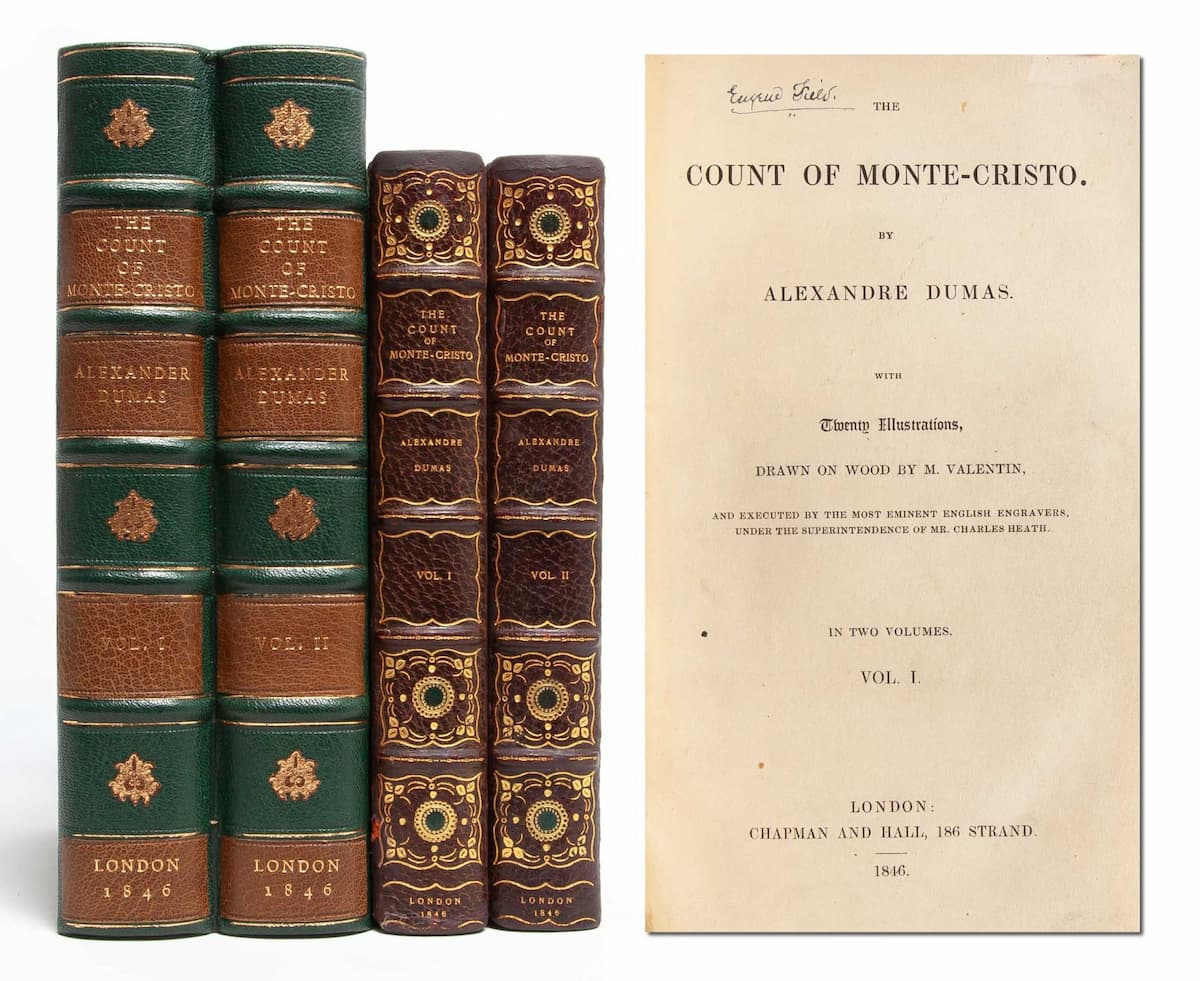

Alexandre Dumas, born on 24 July 1802 in Villers-Cotterêts in the department of Aisne, in Picardy, France, is one of the most famous and widely read French authors. We all know him from his historical novels “The Count of Monte Cristo,” and “The Three Musketeers,” and he even convinced the youngest son of French King Louis-Philippe to build him a dedicated theatre located on the boulevard du Temple in Paris. For roughly three years, the “Théâtre Historique” performed adaptations of his historical novels, and his imaginative tales have since been adapted into nearly 200 films during the early 20th century.

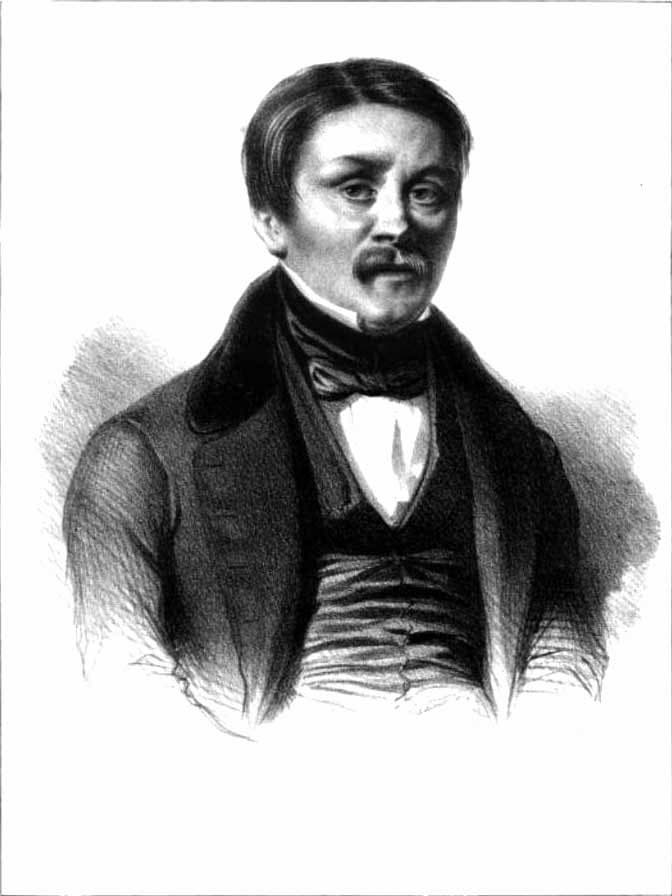

Alexandre Dumas

Of mixed-race ancestry, Dumas was described as “the most generous, large-hearted being in the world. He also was the most delightfully amusing and egotistical creature on the face of the earth. His tongue was like a windmill, and once set in motion, you never knew when he would stop, especially if the theme was himself.”

Hector Berlioz: “La captive, orientale,” Op. 12 “voice, cello, piano” (Marie-Laure Garnier, soprano; Raphaël Jouan, cello; Alphonse Cemin, piano)

Violin Study

Alexandre Dumas: The Count of Monte Cristo

Alexander Dumas readily agreed to collaborate with various composers, even though his own experiences with music were somewhat blotchy. As he himself confessed, his ear was so poor that he gave up the violin after three years of study because, at the end of that time, he couldn’t even manage to get the instrument in tune. “Imagine,” he writes, “what it was like when I had the misfortune to play it. My fiercest enemies date from that period.”

Dumas described himself as “the least music-loving man I know, I must admit it to my shame. I possess a larynx so lacking in instrumental organisation that it has always been impossible for me to reproduce a melody without disfiguring it so completely that I would defy the composer himself to recognise it as it emerges from my mouth, however great his paternal love for the poor child I mutilate.”

Edmond Guion: “Amore, printemps” (Karine Deshayes, mezzo-soprano; Alphonse Cemin, piano)

Simplicity of Melody

Hippolyte Monpou

For the author and poet, learning music and complicated instrumentation held no interest. However, “if a simple, melancholic motif appears, I feel flooded with an infinite sweetness; a fluid harmony envelops me, all my sensitive pores open, my innermost faculties go out to it as if to celebrate it; and thereupon, like the shepherd in the tale of the Sleeping Beauty, it penetrates the furthest recesses of my heart to find a slumbering siren who awakens and sings. Now it is here that the anomaly becomes odd, for I hear this inner music but am incapable of reproducing it; my soul sings in tune, I listen to it, and the time that state lasts will vary according to how deep the impression has been.”

Dumas was a renowned author of adventure and historical novels, and he also wrote serials, magazine articles, travel books, and theatrical plays. It is hardly surprising that he was approached by a number of composers hoping that he would write opera librettos. One such composer was Hippolyte Monpou (1804-1841), who was looking for a suitable text for his opera Piquillo. Monpou started out as an organist and graduated as a composer of operas. Piquillo dates from 1837 and it was slammed by critics. “This opera bears evident traces of a self-sufficient and ignorant composer of romances, a slovenly and incorrect musician, and a poor instrumentalist which we know Monpou to have been; but quite as apparent are melody, dramatic fire and instinct, and a certain happy knack. He never became a really good musician.” The libretto of Dumas was not mentioned.

Hippolyte Monpou: Piquillo, “Ah! Pour votre assistance, seigneur, j’ai l’espérance” (Marie-Laure Garnier, soprano; Karine Deshayes, mezzo-soprano; Kaëlig Boché, tenor; Alphonse Cemin, piano)

Operatic Collaborations

Le roman d’Elvire, Act 3

Dumas’ collaboration with Ambroise Thomas (1811-1896) on Le roman d’Elvire proved only slightly more successful. Dumas worked with Adolphe de Leuven on a libretto destined for the Opéra-Comique, which saw the handsome Gennaro d’Abani refusing to marry the beautiful, and wealthy Elvire. He wants to concentrate on his diamond business, but Elvire exacts her revenge by passing off as an old woman, courtesy of magic potions provided by a gypsy fortune-teller. She attracts the courtship of Palermo’s chief of police, and when Gennaro’s financial ventures have failed, he is pursued by moneylenders. In desperation, he accepts an offer of marriage from the “old woman” and the financial protection she can provide.

Gennaro is decidedly unhappy with the old woman and decides to flee, but instead of a sleeping potion, the gypsy turns Elvire back into a beautiful woman. The people of Palermo are convinced that Gennaro has murdered his wife and has replaced her with this new young woman. When he is about to be hanged, Elvire offers to take another potion which will turn her back into an old woman. Horrified at the prospect, Gennaro professes that he would rather be hanged.

Elvire takes this as a sign of his love and reveals the truth, with the couple living happily ever after. The opera ran for 33 performances to mixed reviews, and it put an end to Dumas’ involvement with opera, which had also included Samson set by Gilbert Duprez in 1856, and La Bacchante set by Eugène Gautier in 1858. We do know that Dumas promised Vincenzo Bellini a libretto for Pasquale Bruno, but sadly, the composer died before work started in earnest.

Ambroise Thomas: Le roman d’Elvire, Act II: Récitatif et air. “Ah ! Vive Dieu !. . . Suprême puissance”

National Anthem

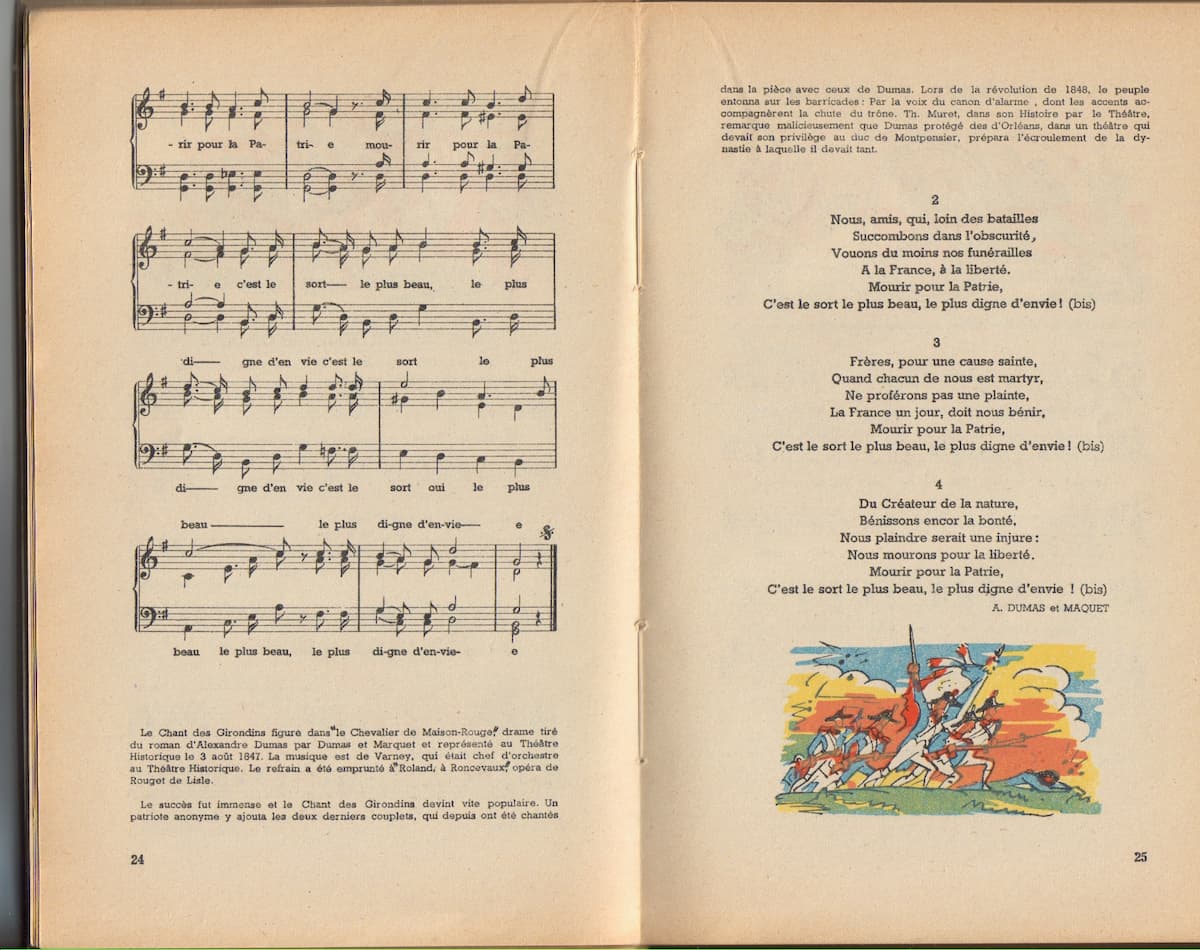

Chant des Girondins

Dumas published his novel Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge in 1845 and set it in Paris during the Reign of Terror. The story is based on an attempt by the Marquis Alexandre Gonsse de Rougeville to communicate with Marie Antoinette in prison by hiding a secret message in the petals of a carnation. Dumas’ imaginative narrative follows the adventures of brave Maurice Lindey who unwittingly becomes involved in a Royalist plot to rescue Marie Antoinette from prison. Maurice is devoted to the Republican cause, but when he falls in love with a beautiful woman, it leads him straight into the service of the mysterious Knight of Maison-Rouge, the mastermind behind the plot.

The novel was adapted for the musical stage by Alphonse Varney, a violinist and highly regarded conductor who had learned his craft under Antoine Reicha at the Paris Conservatoire. He was employed at the aforementioned “Théâtre Historique,” and the famous “Chant des Girondins” from Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge became the national anthem of the French Second Republic. The verses are by Dumas, and the refrain borrows from Claude-Joseph Rouget de Lisle, the author of La Marseillaise.

By the voice of the alarm gun

France calls her children,

“Come,” said the soldier, to arms!

It’s my mother, I defend her.

Dying for the Fatherland

Dying for the Fatherland

It is the most beautiful, most desirable fate

It is the most beautiful, most desirable fate

We, friends, who far from the battles

Succumbing in the darkness,

Let us at least take our funeral

To France, to freedom.

(Refrain)

Brothers, for a holy cause,

When each of us is martyred,

Do not make a complaint,

France, one day ought to bless us.

(Refrain)

From the Creator of Nature,

Let us still bless the goodness,

Complaining would be an insult,

We die for freedom.

(Refrain)

Alphonse Varney: Le chevalier de Maison-Rouge, “Le Chant des Girondin”

Poetry and Music

La Sylphide Bourbon, A.M. Bininger & Co. Bourbon advertising label in the shape of a glass showing a man pursuing three sylphs

Theatrical productions aside, Dumas was convinced that “poetry did not like music, because it was music itself. So when poetry has dealings with music, she is dealing not with a sister, but with a rival. For if music does poetry the honour of creating a score with her, under the pretext of granting her hospitality, she will lead poetry to the stronghold of Procrustes; she will lay her down on her own bed, that is to say on a veritable instrument of torture. If the verses are too short, she will stretch them, at the risk of dislocating them, until they are of the desired length. If the verses are too long, she will trim them, at the risk of crippling them, until they are shortened as she requires. If she has need of an extra syllable, she will add one.”

Although Dumas thought poetry and music to be completely incompatible, a substantial list of composers borrowed his verses, including such illustrious names as Hector Berlioz, César Franck, and Franz Liszt. In his Feuillets d’Album of 1850, Hector Berlioz set to music Dumas’ poem “La belle Isabeau.” The “beautiful Isabelle” was actually Isabeau de Clugny, the daughter of Madame de Clugny and an Afro-Caribbean man from Saint-Domingue. Isabeau lived in Paris during the reign of Louis XVI, and she was said to have been a fashionable woman and “as wealthy as she was free in terms of speech.” She certainly inspired Dumas and, by extension, Hector Berlioz.

On the black mountain,

At the foot of the old castle,

I heard them tell the tale

Of young Isabeau.

She was your age,

With black hair and blue eyes.

Children, the storm is brewing!

Fall to your knees! Pray to God!

The fair young maiden

Loved a knight.

Her father, like a jailer,

Kept her behind bars.

The fickle knight

Had seen her in church.

One evening, Isabeau

Suddenly saw the paladin

Enter her prison cell

Without fear or qualms.

The hurricane raged,

The sky was ablaze.

Children, the storm is brewing!

Fall to your knees! Pray to God!

Isabelle’s heart

Filled with fear:

‘But where,’ she said,

‘Can the chaplain be?’

He is, as he is wont to be,

At his prayers in church.

‘Come with me! Before dawn

We shall be back!’

Her father, alas, from that day on,

Awaits her still.

Children, the storm is brewing!

Fall to your knees! Pray to God

(Translation Richard Stokes)

Hector Berlioz: Feuillets d’Album “La Belle Isabeau,” Op. 19, No. 5

Mélodie

César Franck (1822-1890) composed a total of 22 mélodies and 6 duos for voice and piano. A good many of these settings could be classified as “Romances,” a form of vocal music “which can arouse a singular emotion in the listener with the naivety of its verse and its melodic repetition.” From a poetic point of view, the romance is distinguished by its idealisation of the past and nostalgia for bygone days, one of Dumas’ favourite literary devices. Franck set Dumas’ Le Sylphe during his teenage years, and he accompanied the voice with the addition of the cello, evoking a shadow, a nothing, a dream.

I am a sylph, a shade, a nothing, a dream

An inhabitant of air, a spirit of mystery,

A faint perfume, lifted by the breeze,

The circle of life, joining man to immortality.

Transparent rays drift from my body

And mingle with the vapours of the night;

Only souls in their dreams can see me:

From the heathen I stay out of sight.

On the lake, a shimmering mist hangs low

As I gently skim the reeds.

I hang in the air with wings a-glow

And admire the reflection I see.

Sometimes I leap through your gardens

Intoxicated by the scent

And when I hang in the chalice of the flowers

Not a single stalk will be bent.

I enter your house with assurance

And dance for your child in his sleep;

Then onto his brow and his half-closed eyes

I pour sweet dreams of hope.

When the night throws her canopy over you

I fly up like a thread of gold

And men look up and say: ‘It is a star,

The death of a friend foretold.’

César Franck: “Le Sylphe” (Tassis Christoyannis, baritone; Enrico Graziani, cello; Jeff Cohen, piano)

Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher

Jeanne d’Arc

Alexandre Dumas and Franz Liszt first met in 1832 and immediately developed a close friendship. Liszt much enjoyed Dumas’ drama “Antony,” and he was the only literary personality besides Victor Hugo, with whom Liszt considered it worth spending his time. Both were deeply interested in Jeanne d’Arc, the peasant girl whose victories in battle and gruesome death inspired a long list of literary and musical works. Initially, Liszt had hoped to persuade Dumas to create a ”Faust” libretto, but in the end, he had to settle for the dramatic verse “Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher.” In fact, Liszt composed a number of versions but only published his song in 1876. It is one of his most dramatic late songs, opening with a slow and agonizing musical uncertainty and progressing via a transparent prayer to an illuminating with the saint’s ascension into heaven.

O Lord! I was a shepherdess

When You took me from my hamlet

To drive out the foreign race,

As I used to drive my flock.

In the night of my ignorance,

You came in search of me.

I am to go to the stake,

And yet I saved France.

O Lord God! I am content

To offer myself as sacrifice.

But they say it is most painful,

This death that I shall suffer.

Shall I march without stumbling

Into the final, imminent battle?

I am to go to the stake,

And yet I saved France.

Bring me my banner

Where, blessed for victory,

The sacred names of Jesus Christ

And his Mother are united.

I wish my dying gaze to fasten

On this symbol of hope.

I am to go to the stake,

And yet I saved France.

(Translation Richard Stokes)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: “Jeanne d’Arc au bucher” (Anna Prohaska, soprano; Eric Schneider, piano)