It is often said that musicians — particularly performers — and athletes behave similarly. As a matter of fact, it is quite true. Aside from the physical, training and practice aspect of their activity, both are bound to dedication, discipline, sacrifice, regularity and repetition. A performer follows a strict daily routine of practice and exercises bound by challenges and goals. While there is no point in exaggerated and lengthy-working sessions, the performer needs to devote considerable time, not only to develop and improve, but also to maintain his level. In Armstrong’s own words, “If I don’t practice for a day, I know it. If I don’t practice for two days, the critics know it. And if I don’t practice for three days, the public knows it”. Skills — and talent — is akin to a wall that is built, step after step, brick by brick. Aristotle himself used to say, “excellence is an art won by training and habituation”. But what about composers? Is there such a thing as a habit of creation? Does one practice creativity? Can one create constantly? Does creativity sustain itself through regularity? Can one judge creative progress? Well, yes indeed.

It is often said that musicians — particularly performers — and athletes behave similarly. As a matter of fact, it is quite true. Aside from the physical, training and practice aspect of their activity, both are bound to dedication, discipline, sacrifice, regularity and repetition. A performer follows a strict daily routine of practice and exercises bound by challenges and goals. While there is no point in exaggerated and lengthy-working sessions, the performer needs to devote considerable time, not only to develop and improve, but also to maintain his level. In Armstrong’s own words, “If I don’t practice for a day, I know it. If I don’t practice for two days, the critics know it. And if I don’t practice for three days, the public knows it”. Skills — and talent — is akin to a wall that is built, step after step, brick by brick. Aristotle himself used to say, “excellence is an art won by training and habituation”. But what about composers? Is there such a thing as a habit of creation? Does one practice creativity? Can one create constantly? Does creativity sustain itself through regularity? Can one judge creative progress? Well, yes indeed.

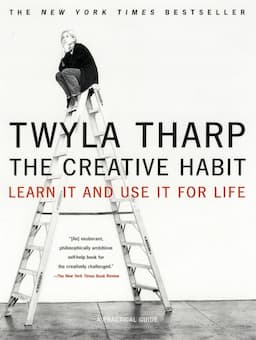

The following ideas are of course inspired by Twyla Tharp’s book The Creative Habit. The American choreographer is well-known for having ignored the boundaries of music genres throughout her career spanning over fifty years; working with the likes of Paul Simon, David Byrne, Elfman, Glass and with Miloš Forman for “Hair” and “Amadeus”. She is also known for being an example of prolificacy and collaboration. Two of her most famous books elaborate on her experience in both self-discipline and creativity, as well as collaboration. The Creative Habit released in 2003 is an eloquent book for many artists and unravels the secrets behind discipline at the service of creativity.

© Isthmus

In my experience, there seems to be two steps in the creative process of the composer. An absorbing state and a releasing one; in other words, learning and creating. Learning comes in many different ways, such as studying — composers relentlessly study their colleagues’ work and scores —, cultivating one’s mind — composers surround themselves with inspiration — and seeking inspiration in other arts — literature, visual arts; all major creative leaps have been taken thanks to external influences; Debussy, Cage, Xenakis… Creating is of course an evident process which I shall not dive in deep for the purpose of this article. Applying this double-side process regularly creates a flow of ideas, a constant boil of inspiration and an eagerness for the composer to develop himself and create more. In all, a snowball effect…

There are a few rules, or commandments, that a composer can follow in order to develop a creative habit. When treated like life mantras, these are recipes for creative success. Here are five suggestions.

• One must learn, every day, with an open mind;

• One must create, every day, with no judgement;

• One must not throw away material;

• One must work on different creative streams;

• One must give time for ideas to evolve.

When Bach wrote, it was out of duty as much as creative hunger, it was therefore facilitated by the composer’s own professional activity. As musicians slowly took distance from the directions of their patrons, the myth of inspiration striking the composer in the midst of the night settled in…

Nadia Boulanger © img.discogs.com

So how can one judge creative progress? It seems that when it comes to creativity, progress can be defined as both achievement of goals, and growth. When one can look back at his own work and observe it from a third-person point of view, as if stranger to it, then he has successfully created the artistic distance through his creative progress. Creativity is just like a stew; it needs to cook slowly, with constant attention and heat, developing the flavours and aromas over time. Once such creative habits are taken, it is like a spiral of creative exhilaration and satisfaction. Of course, this does not apply to composers only, writers do it too, as well as all artists in general — in fact, anything that needs creativity can benefit from regularity. But most importantly, and paraphrasing the French composer and teacher Nadia Boulanger, the essential conditions of everything one does must be choice, love, and passion.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter