A good number of instrumental works, specifically pieces written for piano solo in the 19th and 20th-century, carry the title “Nocturne.” The word comes from the French, meaning “nocturnal” or “night”, and it suggests the magical atmosphere of peace and serenity evoked and inspired by the night.

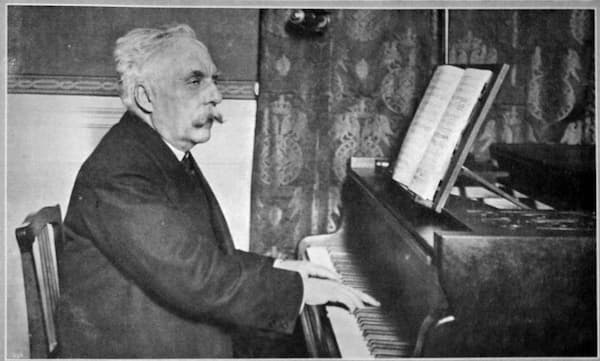

Gabriel Fauré

This musical evocation of the night essentially unfolded as a character piece, entirely free in form and exuberant in expression. The French critic Émile Vuillermoz writes, “the nocturne is not a definite musical form. It is a psychological mood, a state of mind. The nocturne is the most complete realisation of man at peace with the magic of the elements.”

Music history credits the Irish composer and pianist John Field with publishing the first composition for solo piano specifically designated “Nocturne.” And his 18 highly lyrical nocturnes are still among his most popular works. The most famous exponent of this new genre was Frédéric Chopin, who, between 1827 and 1846, wrote a total of 21 compositions under that specific title. In these two blogs, however, we will listen to the 13 Nocturnes of great poetic creativity composed by Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924).

Fauré composed nocturnes throughout his life, with the first dating from 1883 and the last written in 1922. These pieces, according to a scholar, “bear witness to the admirable stylistic evolution of the composer, gradually revealing a profundity that could hardly have been foreseen in the early ones.” In his nocturnes, Fauré found his own personal voice, with luscious melodies filtered as through a veil.

For some commentators, these works tend towards reverie, “a meditation on states of mind devoid of inordinate darkness or drama.” As Philippe Fauré-Fremiet, one of the composer’s sons related, “They evoke the secret communion of humanity with things invisible.”

Nocturne No. 1 in E-flat minor, Op. 33, No. 1

Composed in 1875 and dedicated to Madame Marguerite Baugnies, the Nocturne No. 1 in E-flat minor, Op. 33, No. 1, is one of the most beautiful early works crafted by Fauré. Already showing a great maturity of expression, the opening unfolds as a slow and expressive melody accompanied by chords. Some commentators hear “a feeling of profound sadness, intensified by the controlled passion of Fauré’s compositional style.”

Gabriel Fauré’s Nocturne No. 1

A more animated second theme transports us into the realm of C Major, and the opening theme gracefully returns. The great pianist Alfred Cortot wrote, “Neither the elegance nor the ingenuity of the preceding works have revealed with such personality, the quality of the pianistic creativity of M. Fauré. Everything is new in this nocturne, inspiration, tonal relations, form, and instrumental style.”

Nocturne No. 2 in E-flat Major, Op. 33, No. 2

Gabriel Fauré

Gabriel Fauré: Nocturne No.2 in E-flat Major, Op. 33, No. 2 (Philippe Cassard, piano)

Composed around 1881, the Nocturne No. 2 in B Major, Op. 33, No. 3 follows the pattern established in the first work. The opening “cantando” presents a song without words, regaling in the joys of an atmospheric night. This intimate duet between two intertwining voices is quickly interrupted by a turbulent toccata in the minor key.

Leaping octaves are soon traversed by a lush, lyrical melody, with a Chopinesque trill reintroducing the initial song without words. The toccata does make a brief reappearance, yet the work concludes with a short and whispered coda.

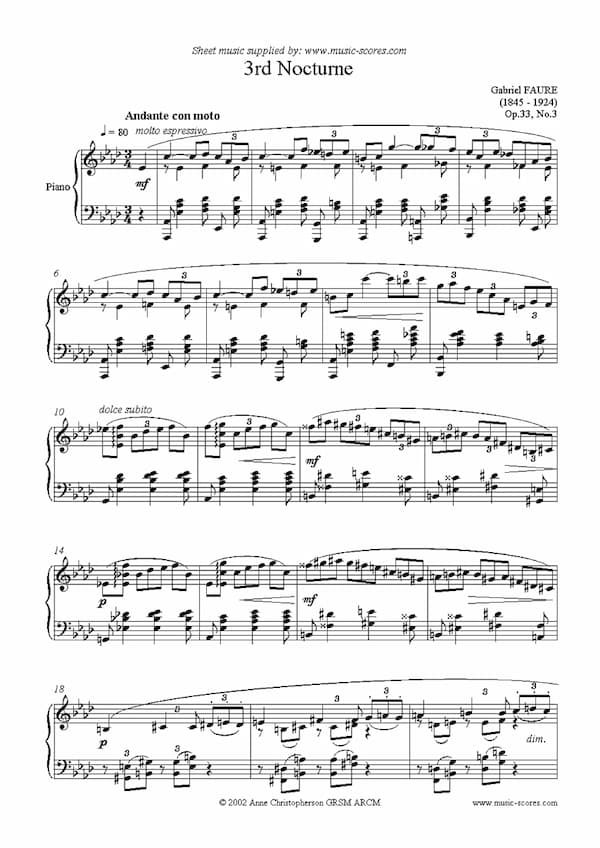

Nocturne No. 3 in A-flat Major, Op. 33, No. 3

The Nocturne No. 3 in A-flat Major, Op. 33 No. 3 dates from 1883, and it might easily have become a typical salon piece. The gorgeous opening melody flows above a bass line of outlying octaves and inner chords. And almost immediately, the syncopated accompaniment and delicate cross-rhythms signal a much more rarefied composition.

Gabriel Fauré’s Nocturne No. 3

The melodic fragment that concludes the first theme becomes the basis for a second idea, now played by the left hand and accompanied by a single line above. When the opening section returns, the accompaniment is now in triplets rather than chords, and the coda provides delicious harmonic subtleties and a dreamlike ending.

Nocturne No. 4 in E-flat Major, Op. 36

Written in 1884, the Nocturne No. 4 in E-flat Major, Op. 36 is dedicated to Madame la Comtesse de Mercy-Argenteau. It displays all the charms the young Fauré had on offer, mingling with feigned nonchalance and a singing theme. The atmosphere is rather sombre, however, with the accompaniment resembling the tolling of a bell around a constantly moving background of sixteenth notes.

Combining lyricism with drama and passion, the lovely “cantando” episode reaches the heights of lyrical expression, yet the characteristic restraint of Fauré is always present. The initial theme returns with a sense of growing calmness, and a coda brings this irresistible piece to a gentle conclusion. The stunning contrast between clearly-defined sections appears not only in their accompaniment but also by distinct modulations and cadences.

Nocturne No. 5 in B-flat Major, Op. 37

Gabriel Fauré’s Nocturne No. 5

Gabriel Fauré: Nocturne No. 5 in B-flat Major, Op. 37 (Aline Piboule, piano)

Fauré showed his early Ballade Op. 19 to Franz Liszt, who instantly sight-read through the entire piece. Apparently, he declared, “I’ve run out of fingers.” When Fauré embarked on the composition of his Nocturne No. 5 in B-flat Major, Op. 37, in 1884, the influence of Chopin seemed to have passed. Instead, the rhetorical gestures of this Nocturne suggest the lingering influence of Liszt.

With syncopation one of Fauré’s favourite rhythmical devices, it dominates the first and final section of this nocturne. We still hear the sensuality of early nocturnes, but they now take on a more sombre inflection. The little decorative arabesque near the beginning takes on new meaning and significance, as it transmogrifies into a stormy and whirling figuration in the central section. A noted performer wrote, “through the dissonances with the melodic line which they create, syncopations allow shimmering feelings and colours that are only suggested while keeping the pulse of the music.”

Nocturne No. 6 in D-flat Major, Op. 63

Gabriel Fauré’s Nocturne No. 6

The Nocturne No. 6 in D-flat Major, Op. 63 was completed on 3 August 1894 and is dedicated to Monsieur Eugene d’Eichthal. One of the most passionate and moving works in all of piano literature, “this masterpiece from Fauré’s middle period is certainly the summit of his 13 nocturnes because of its penetrating poetry, clarity, and brilliance.”

A beautifully expressive theme unfolds in a meditative and entirely introspective manner. Fauré’s son told the story that when someone demanded to know under what marvellous sky he had conceived the inspiration for the beginning of the Nocturne No. 6, his father responded, “in the tunnel of the Simplon,” one of the longest rail tunnels in the world. Gradually, we are transported into an unsettled and unstable section leading to a highly expressive climax.

In the central section, Fauré exploits the upper register of the piano by presenting an extended cantabile melody. With an ethereal accompaniment and angelic melodic figures, “this section creates a weightless, celestial atmosphere before uncertainly begins to creep in. Cortot remarked on this nocturne, “the work of M. Fauré, the most perfect to our taste with the theme and variations.” After a fermata, the opening section returns but adds a much more developed and passionate coda. I trust you enjoyed the first instalment of the magnificent nocturnes by Gabriel Fauré; stay tuned for episode 2.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter