“In Silence, we can truly hear the voice of God”

John Tavener

Ten years ago, on 12 November 2013, the British composer John Tavener (1944-2013) died at his home in Child Okeford, Dorset. Tavener had been battling considerable health problems throughout his life, ranging from a stroke in his thirties, heart surgery and the removal of a tumour in his forties, and two successive heart attacks that left him weakened. In 1990, Tavener was diagnosed with Marfan syndrome, a multi-systemic genetic disorder that affects the connective tissue.

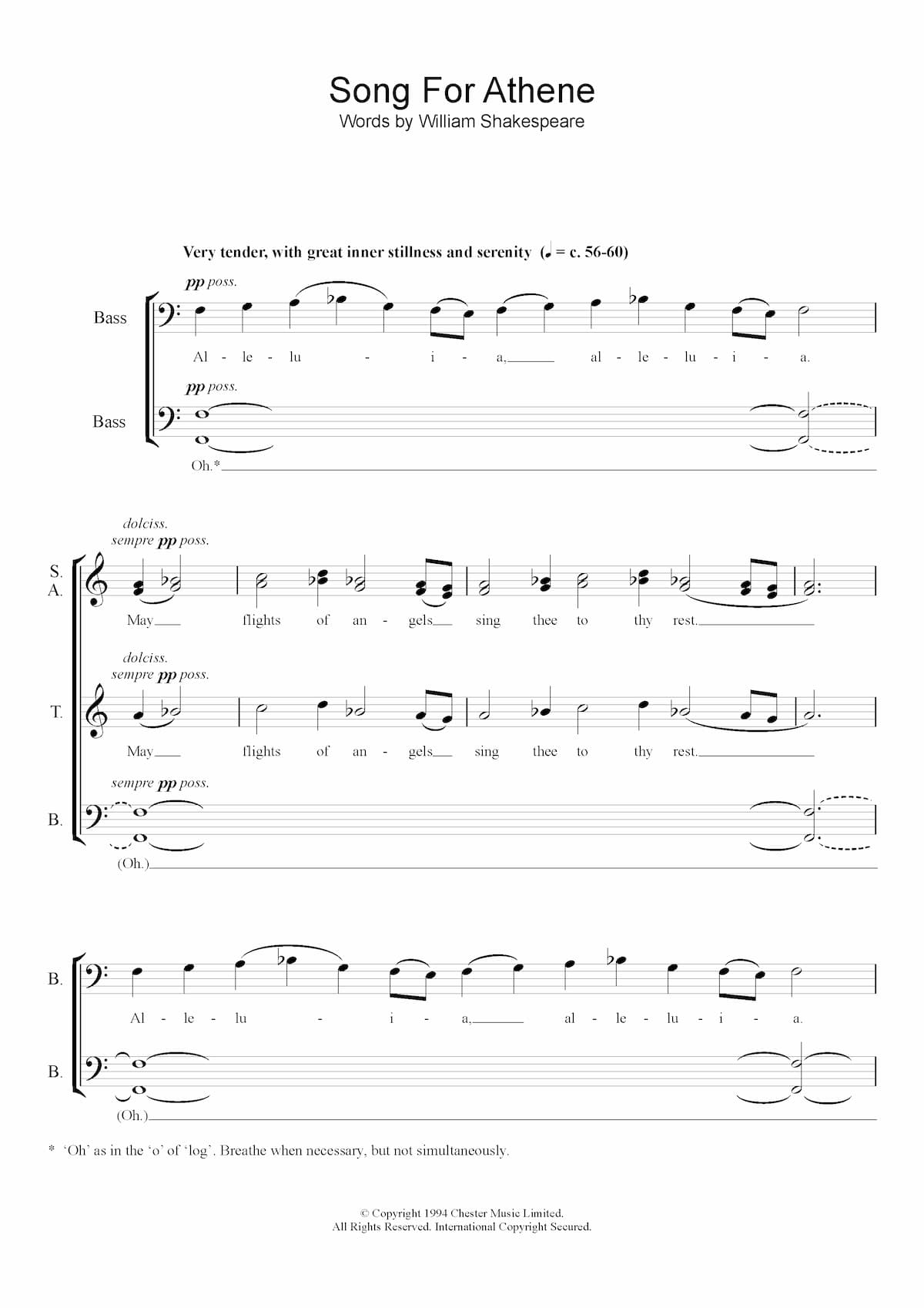

John Tavener, who was knighted in 2000 for his service to music, was known for his innovative and mystical approach. His musical style was marked by a deep spirituality, drawing inspiration from various religious traditions and exploring themes of faith, love, and transcendence. The Protecting Veil topped the classical charts for several months, while his Song For Athene was sung at the funeral of Princess Diana.

John Tavener: Song For Athene

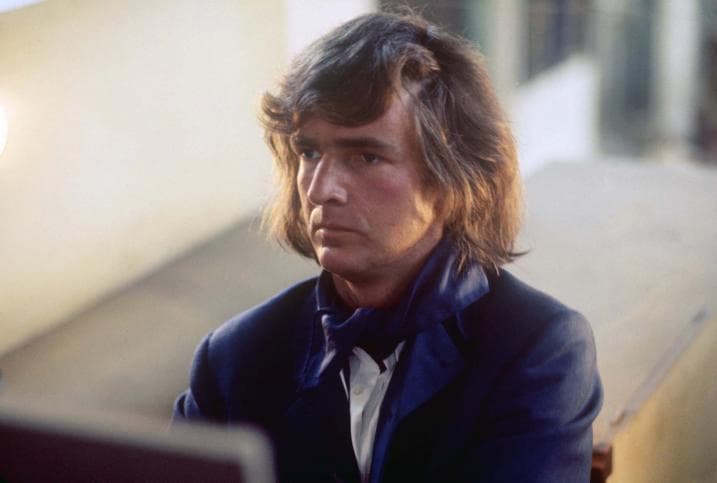

In the Beginning

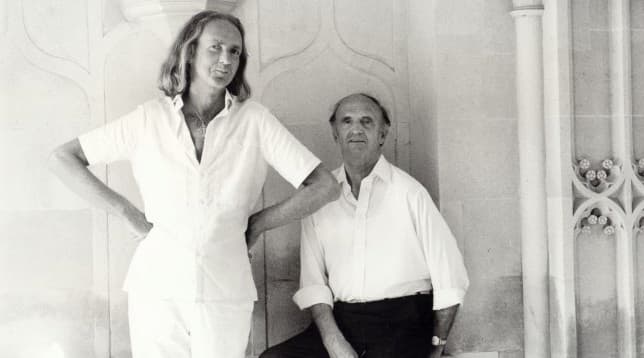

John Tavener and his father

Born on 28 January 1944 in London, John discovered the piano at an early age, enthusiastically imitating rain, wind, and thunder. He grew up in an intellectual and creative environment as his father was an artist, and his mother had a great love for literature and poetry. John loved to improvise and compose at the piano, and he won a music scholarship to Highgate School, starting formal music lessons in piano, organ, and composition. Two of his early works, a setting of the Credo and Genesis were performed at St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, where his father, and he himself, was active as an organist.

Two other composers were studying at Highgate at the time, Brian Chapple and John Rutter. Rutter remembered that he was in awe of Tavener’s natural gifts. “He had perfect pitch and a very analytical ear for musical colour. You could play a ten-part chord to him, horribly dissonant, and he’d pick out every note, just like the colours in the rainbow. His natural musical equipment was so formidably tuned to whatever he heard, whatever appealed to him, was instantly absorbed.”

John Tavener: The Protecting Veil

Royal Academy of Music

John Tavener: Song for Athene

By July 1961, Tavener played the Shostakovich Second Piano Concerto at the Wigmore Hall for the National Youth Orchestra audition, and one year later, he entered the Royal Academy of Music. He studied piano with Solomon, but more significantly, composition with Lennox Berkely. A biographer writes, “Tavener loved Berkeley not for his music but for his human qualities: his eccentricity, his gentleness, and his famous modesty.” Berkeley had been a fervent Catholic ever since he was converted by Nadia Boulanger, and he also passed on his knowledge of contemporary music, particularly Messiaen and Boulez.

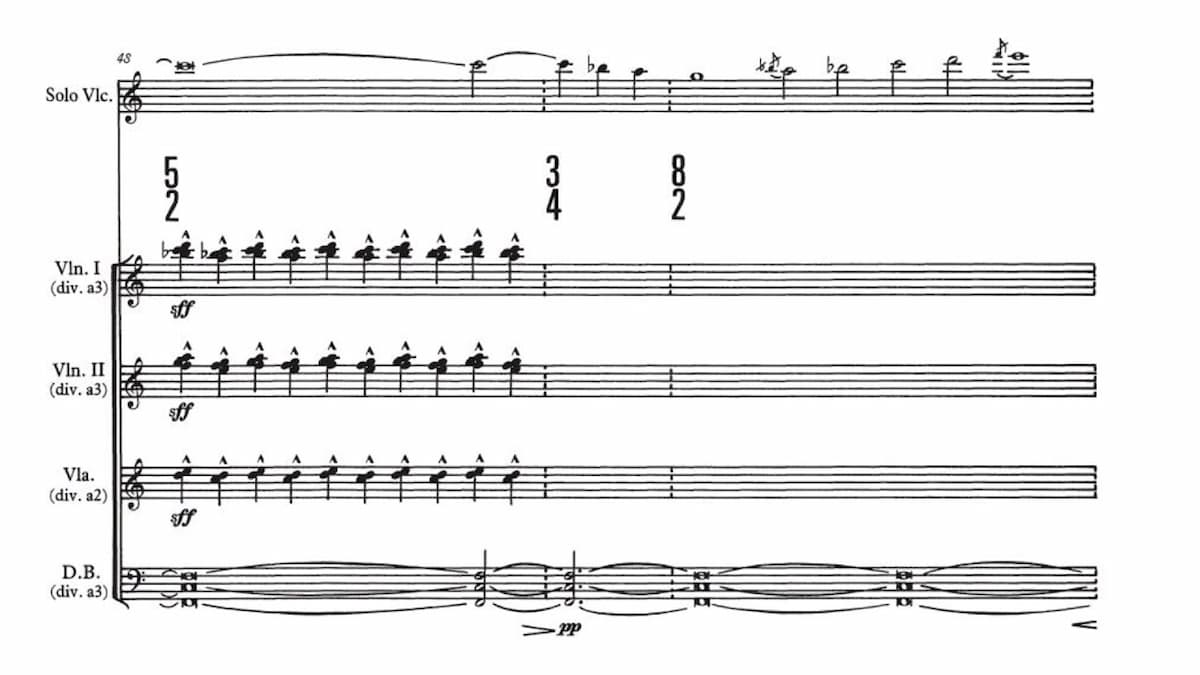

Blending Beethoven, Stravinsky, and Messiaen, Tavener began to shape his unique compositional voice, merging the classical and minimalist with the avant-garde. A critic writes, “The highly gifted Tavener belongs wholly to the present, and his music is full of novel ingenuities of sound and rhythm. His aim, the poetic blending of words and music, is beautifully attained.” During his time at the Academy, his one-act opera The Cappemakers and his song cycle Three Holy Sonnets of John Donne were performed, and he won the Prince Rainier III of Monaco Prize for his cantata Cain and Abel.

John Tavener: In Alium (Eileen Hulse, soprano; Ulster Orchestra; Takuo Yuasa, cond.)

Growing Fame

John Tavener: Choral Collection

Tavener’s career skyrocketed, and his early works “The Whale” and “The Protecting Veil” established him as a rising star on the contemporary music scene. His flamboyant use of collage techniques and recitations was grounded in “the use of stasis and non-developmental block construction.” These two techniques were used for metaphysical exploration and more unified compositions. In fact, “The Whale,” an epic telling of the biblical tale of Jonah and the Whale, was championed by the Beatles and recorded by Apple Records.

Tavener’s devotion to both music and faith was evident from an early age, but the immersion in the doctrines and music of Western Christianity ultimately proved unfulfilling. After a brief marriage to the young Greek ballerina Victoria Maragopoulou, he converted to the Eastern Orthodox Church in 1977. His devotion to this faith would be the guiding force for his work for the rest of his life, as he once explained, “writing music becomes more and more, as I grow older, an act of prayer…The act of composition makes me feel close to God.”

John Tavener: “Hymn to the Mother of God”

The Conversion

For Tavener, music had to be part of tradition but not in the sense of fixation on the idea of artist as genius. Instead he sought to connect to a much earlier tradition in the conventions of Byzantine music, which forms much of the basis of Orthodox church music. “I toured Greece,” he remembered, “noting down fragments. I read academic books with considerable boredom, on the eight tones on which Orthodox services are based.” Initially, Tavener attempted to write exclusively for the Church, but he felt too limited by the idea that his pieces could only be heard once in the Service.

Drawn to orthodox theology and liturgical traditions, Tavener was particularly fascinated by the mysticism of his new faith and that particular knowledge also chanced his system of composition. The drone became central to many of his works, with melodies weaving over sustained chords. It transformed the mood of his music, making it more peaceful and transcendental. Critics called him a minimalist or namby-pamby New Ager, but for Tavener “there is nothing easy about achieving simplicity, as the music crystallises towards ritual and symmetry.

John Tavener: Akhmatova Requiem (Phyllis Bryn-Julson, soprano; John Shirley-Quirk, bass-baritone; BBC Symphony Orchestra; Gennady Rozhdestvensky, cond.)

Legacy

John Tavener: The Protecting Veil

As a composer, Tavener never stopped growing. After reaching a point where “everything I wrote was terribly austere and hidebound by the tonal system of the Orthodox Church, I felt the need in my music to become more universalist, to take in other colours and other languages.” As such, he explored a number of different religious traditions, including Hinduism and Islam. A scholar writes, “the transparency to higher things evident in Tavener’s musical language has left the concerns of the old avant garde far behind and simultaneously brought him a large measure of fame.” His shift in focus resonated with audiences and critics alike and earned him international recognition.

As Tavener wrote, “we seem to have lost our contact with the primordial: the idea of—call it divine revelation as opposed to something that’s learned by the human intellect—something that, if you lay yourself completely open, and you just open your heart completely, something will actually come into it.”

Although his compositions can frequently incline to the formulaic, very few composers of the modern era have had the courage “to deal so concentratedly in music with matters of the spirit.” Tavener was determined to follow his own beliefs into an essentially unfashionable territory. His impact on the contemporary classical music world, however, cannot be overstated. As John Rutter explained, “Tavener had the very rare gift of being able to bring an audience to a deep silence.” The meditative calm and exuberant lyricism of his late works were not written in order to become popular; Tavener, according to Steven Isserlis, “was writing music he had to write.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter