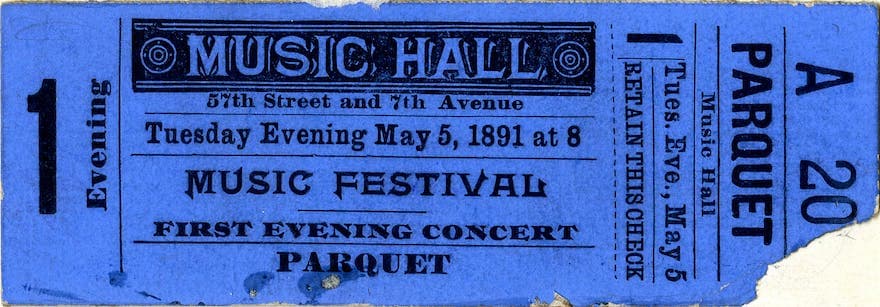

New York audiences and music lovers were treated to a momentous occasion in May 1891. Specifically, they witnessed the inaugural concert at Carnegie Hall, a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City, on 5 May 1891. Carnegie Hall would soon rise to become one of the most prestigious venues in the world of music.

Carnegie Hall in 1895

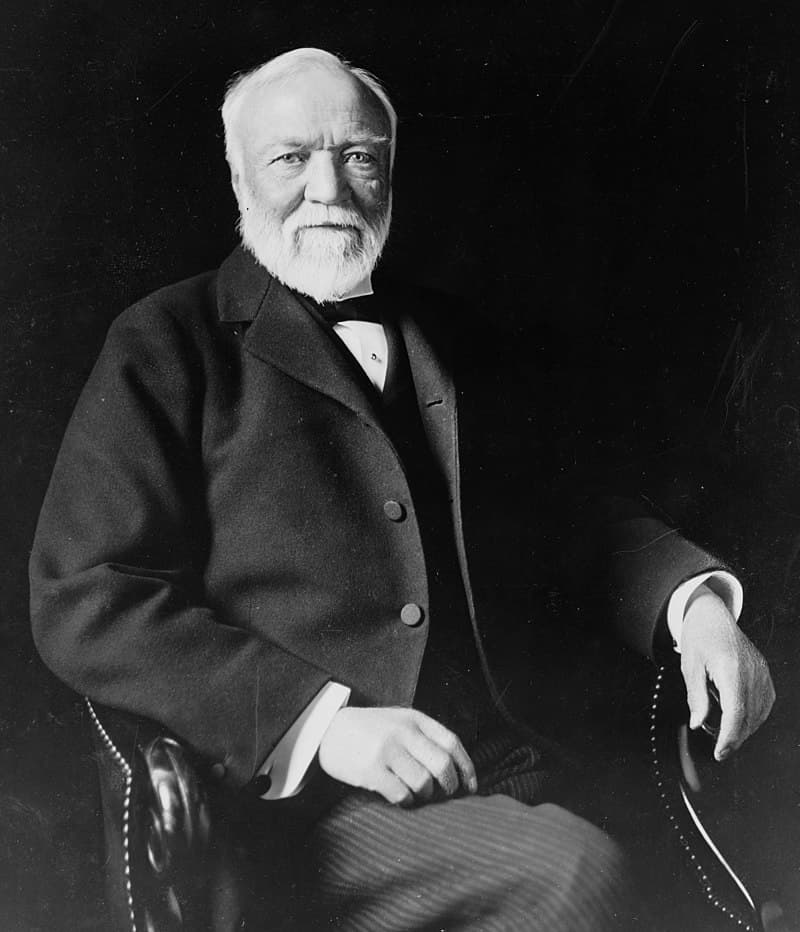

The vision of a dedicated Music Hall was the brainchild of Leopold Damrosch, conductor of the Oratorio Society of New York and the New York Symphony Society. His son Walter, who met the businessman Andrew Carnegie during his studies in Germany, carried Leopold’s vision forward. Eventually, he was able to convince Carnegie to donate 2 million dollars and the Oratorio Society and New York Symphony bought nine lots at the southeast corner of Seventh Avenue and 57th Street.

Andrew Carnegie

They approached architect William Burnet Tuthill, a talented amateur cellist and board member of the Oratorio Society to design the Music Hall. Tuthill had engaged in extensive studies of European concert halls, and he brought his experience with acoustics to bear on the Carnegie Hall project.

“Old Hundred” arr. Vaughan Williams

Designed in a modified Italian Renaissance style, the cornerstone for the Music Hall was laid by Carnegie’s wife Louise on 13 May 1890. Within the next 12 months, the original five-story brick and limestone building “containing a 3,000-seat main hall and several smaller rooms for rehearsals, lectures, concerts, and art exhibitions,” began to take shape. Andrew Carnegie said, “It is built to stand for ages, and during these ages, it is probable that this Hall will intertwine itself with the history of our country.” The Recital Hall opened in March 1891, and the Oratorio Hall in the basement opened on 1 April 1891. The Music Hall officially opened on 5 May 1891, starting a five-day Opening Week Festival.

William Burnet Tuthill

Contemporary reports write of “horse-drawn carriages lining up for a quarter-mile outside, while inside the Main Hall was jammed to capacity.” Conductor Walter Damrosch led the New York Symphony Orchestra and the Oratorio Society on Opening Night, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky had been engaged for a guest appearance. He was apparently paid $5,000 for his service, which in today’s money equates to roughly $150K.

Leonard Bernstein Conducts Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72b

A contemporary eyewitness reports, “People are swarming everywhere trying to get into this magnificent hall. The architecture is absolutely gorgeous with a façade made of terra cotta and iron-spotted brick. I manage to get inside where the main hall is jammed to capacity. I look around to see that the magnificent architecture extends to the inside as well. I looked up at the boxes to see the Rockefellers, Whitneys, Sloans, and Fricks families. I find my seat, smooth my dress, and sit down.”

Carnegie Hall Opening Festival poster

The program opened with the hymn “Old Hundred,” a tune from the second edition of the Genevan Psalter. It is considered one of the best-known melodies in the Western Christian musical tradition, and it was the first work transmitted by telephone during Graham Bell’s first demo at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1876. Bishop Henry Codman Potter delivered a lengthy speech praising Carnegie’s philanthropy. Walter Damrosch entered the stage and the hall erupted in applause. The New York Symphony played “America,” and Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3. A member of the audience reported, “The acoustics are even better than I could imagine.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Marche solennelle

Then it was Tchaikovsky’s turn. In his diary, he writes, “In a crowded carriage I reached the Music Hall. Illuminate and packed with the public, it made an exceptionally striking and grandiose impression…The pastor gave a long and, it was said, exceptionally tedious speech, and after this, there was a very good performance of the Leonore Overture. Interval. I went downstairs. Excitement. My turn came. I was received very noisily. The march (Marche solennelle) went off beautifully. A great success! I listened to the rest of the concert from Hyde’s box. Berlioz’s “Te Deum” was rather tedious; it was only at the end that I really began to enjoy it.”

Ticket from the Opening Night at Carnegie Hall

Tchaikovsky was also less than enthusiastic about the review he read in the papers the next day. As he records in his diary, “Tchaikovsky is a tall, gray well built interesting man, well on the sixty?!!! He seems a trifle embarrassed and responds to the applause with a succession of brusque and jerky bows. But as soon as he grips the baton his self-confidence returns.”

Carnegie Hall at night

Tchaikovsky was rather annoyed and added, “It makes me angry that they not only write about music, but about me personally. I cannot bear it when they comment on my embarrassment, and marvel at my brusque and jerky bows.” Tchaikovsky did not have much time to ponder the review, as he was in the audience at the second concert, which featured Mendelssohn’s oratorio “Elijah.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Felix Mendelssohn: Elijah (excerpts)