By 1937, David Oistrakh was considered the leading Soviet violinist. He had participated in a good number of competitions and was under tremendous pressure from the government during that time. Gennadi Rozhdestvensky wrote, “Young musicians who took part in competitions at that time had the obligation to win. Your victory wasn’t yours, but that of the people and the system. The same thing for sport! This added colossal pressure. Indeed, everybody followed the results. But you had to win first prize, and if ever you didn’t… watch out!”

David Oistrakh

He need not have worried as David Oistrakh did win. He received first prize at the Ukrainian Violin Competition in 1930, another first prize at the Violin Competition of the Soviet Union in 1935, second prize at the First International Wieniawski Competition in Warsaw, and first prize at the International Ysaÿe competition in 1937. By 1942, he was a member of the Communist Party, but everybody understood that he merely joined the Party in order to survive. Oistrakh was considered a “simple and warmhearted man of great intelligence, charm, sincerity, and integrity who had cultivated his tremendous gifts to their highest point of perfection at the cost of enormous work and concentration. His mastery was absolute. He knew exactly what he wanted to achieve musically and he knew the methods by which to achieve it technically.” It is hardly surprising that a number of eminent Soviet composers were greatly inspired by the violinist and wrote dedicated compositions for him. So let’s go ahead and sample some violin masterworks inspired by the great David Oistrakh.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Violin Concerto No. 1, Op. 77

David Oistrakh and his son Igor

Dmitry Shostakovich first heard David Oistrakh perform in 1935 at the Second All-Union Competition, which Oistrakh won. They first performed together on a tour of Turkey a couple of months later, and eventually started to collaborate on the first movement of the Shostakovich Violin Concerto No. 1, Op. 77. The work took shape at a time of severe censorship and purge, and in the harsh climate of anti-Semitic of post-war Soviet Russia. Shostakovich first played the music at the piano for Oistrakh and his son, Igor, in 1948. David Oistrakh remembered that Shostakovich played “with a virtuosity which itself would have been admirable… if he had not been so deeply moved by the music.” Because of political circumstances, however, the concerto was not released for public consumption until “the political thaw succeeding Stalin’s death in March 1953.”

During the interim seven years between creation and performance, the work seems to have undergone a number of alterations. We do know that David Oistrakh himself not only edited the violin part but also gave “real help in the work’s composition.” For one, Oistrakh requested the composer “to spell the soloist briefly after the cadenza by reassigning the initial statement of the first theme of the finale to the orchestra,” as well as “to give the main theme in the opening of the Finale to a resonant brass instrument, and save the timbre of the violin for later.”

Igor and David Oistrakh

Shostakovich immediately agreed to the changes. Igor Oistrakh seemed to remember that Shostakovich was actually working on “a second version.” Be that as it may, after a dozen rehearsals in the presence of the composer, Oistrakh gave the first performance with Mravinsky and the Leningrad Philharmonic on 29 October 1955. As Oistrakh wrote, the work is “not following easily into one’s hands,” but he declared it an “innovational work, remarkable for the surprising seriousness and depth of its artistic content… which demands complete emotional and intellectual involvement, and gives ample opportunities not only to demonstrate virtuosity but also to reveal deepest feelings, thoughts and moods.”

Nikolai Myaskovsky: Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 44

Nikolai Myaskovsky

Nikolai Myaskovsky (1881-1950) is sometimes called the “Father of the Soviet Symphony.” In the 1920s and 30s he was the leading composer in the USSR, and in all, wrote a total of 27 symphonies plus three sinfoniettas and two concertos. His violin concerto is dedicated to David Oistrakh, and he frequently asked for the violinist’s help on technical issues. In 1938 he wrote, “Dear David Feodorovich, I have been informed, to my great pleasure, that you are prepared to tackle the most thankless task of familiarizing yourself with my experiment in producing a Violin Concerto. Please be pitiless when you judge my work, since, although I have tried to shape the music as attractively and richly as possible, I cannot guarantee the specific technical aspect of the composition… I will consider all your comments with the greatest appreciation, and it would be highly desirable if we could meet for a discussion and consider all doubtful points.”

Nikolai Yakovlevich Myaskovsky: Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 44 (Vadim Repin, violin; Kirov Orchestra; Valery Gergiev, cond.)

Oistrakh in turn showed great interest in the Myaskovsky concerto and he quickly replied. “Dear Nikolai Jakovlevich, I have just received your letter and the Concerto (violin score and piano extracts), which I awaited with the greatest interest and impatience. I immediately liked your Concerto tremendously after playing it for the first time. My love for your excellent composition grows stronger every day. At the moment, my enthusiasm for the Concerto is so great that I play nothing else. In addition to this, I find the music deeply searching and extremely attractive, the Concerto is very varied and rich, as far as using the violinistic possibilities is concerned. I will make every effort to communicate the Concerto as well as possible. I would very much like to meet you to discuss a few details, which are of course of no real significance, but should be clarified.” Oistrakh premiered the concerto on 10 January 1939 in Moscow to great success, and the press was ecstatic.

Sergei Prokofiev: Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 80

David Oistrakh and Sergei Prokofiev playing chess

Young David Oistrakh was tasked with performing the “Scherzo” from Prokofiev’s 1st Violin Concerto at a banquet in the composer’s honor. Oistrakh remembers seeing Prokofiev’s expression as he listened. “The longer I played, the more grave his face became. And when I finished, Prokofiev did not join in the applause. Paying no attention to the excitement of the audience, he walked toward the stage and asked my accompanist to let him have his place at the piano. Then turning to me, he said, “Young man, you don’t play it as it should be played,” and right then and there he began to explain and to show me the character of his composition.”

In time, composer and performer would enjoy a close friendship and Prokofiev dedicated two violin sonatas to Oistrakh. Oistrakh recalled the first time he laid eyes on the Sonata No. 1 in F minor. “I remember that summer day of 1946. The impression was huge: I realized that I was witnessing something extremely great and important. In fact, an equally beautiful and deep work (it can be said so without any exaggeration) has not appeared in the world of violin music for many decades.” And he added, “The F-minor Sonata is a tremendous epic work in which the picture of the past of our great country lives again and in which the composer’s thoughts about his people’s fate take from. I am deeply convinced that this work, because of its purposeful contents and its extraordinary mastery in the realization of its purpose, the beauty of the musical pictures can be counted as one of the most outstanding violin sonatas of world literature.” In fact, Oistrakh played the “Andante assai” movement at Prokofiev’s funeral in Moscow in 1953.

Sergei Prokofiev: Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2 in D Major, Op. 94b

David Oistrakh, Shostakovich and Lev Oborin

The Violin Sonata No. 2 in D Major carries the unusual opus number 94b. In fact, it is a new incarnation of the Sonata in D Major for flute and piano, Op. 94, a work Prokofiev wrote during the war. After listening to the original version, Oistrakh suggested: “that it can sound very good on a violin in a more full-blooded shape, so to speak.” As the violinist remembers, “I shared my thoughts with Sergei and we decided to meet. It was the first time I had the opportunity to observe him at work; I saw how you could work carefully and thoughtfully. Everything went very quickly: at Prokofiev’s request, I prepared a few variants for each revised fragment, numbered them, and presented them to the author who, with a pencil in his hand, marked what he considered appropriate, made a few corrections, and thus, without unnecessary words, the violin version of the Sonata was created.”

The polar opposite to Prokofiev’s 1st Sonata, opus 94b is one of the composer’s most cheerful and carefree works. While the first theme of the introductory “Moderate” serves as an example of a characteristic Prokofiev lyricism, the second theme is a refined musical joke. Oistrakh believed that this collaboration with Prokofiev produced a more exciting and aggressive violin version. During rehearsals with Lev Oborin, Oistrakh confessed, “I never worked with such passion on any other work…Until the Sonata’s first public performance, I couldn’t play or think about anything else.” Oistrakh and Oborin first performed the work in Moscow on 17 June 1944. Not everybody was happy, however. Sviatoslav Richter, who performed the premiere of the Sonata in the original version, firmly believed that “the flute version is incomparably better.”

Aram Khachaturian: Violin Concerto in D Minor

Aram Khachaturian and David Oistrakh

David Oistrakh also made significant contributions to the Khachaturian Violin concerto. The composer remembers, “I was writing the Concerto with Oistrakh in mind and it was a great responsibility… Oistrakh said he would like to hear the Concerto and invited me to his country home. I played it for him, trying for some degree of synthesis—I would play the harmony with my left hand and the violin part with my right, singing some of the cantilena parts and the violin melody with the entire accompaniment. Oistrakh carefully followed the score. He liked the Concerto and asked me to leave it with him as we agreed to meet again in a few days.” And Oistrakh recalls, “I came to know him quite well while the Violin Concerto was being written. I remember that summer day in 1940 when he first played the Violin Concerto, which he had just finished. He was so totally immersed in it that he went immediately to the piano. The stirring rhythms, characteristic tunes of national folklore, and sweeping melodic themes captivated me at once. He played with tremendous enthusiasm. One could still feel in his playing that artistic fire with which he had created the music. Sincere and original, replete with melodic beauty and folk colors, it seemed to sparkle.”

Composer and performer closely collaborated on the work and made “many corrections in details and nuances.” Oistrakh found working with Khachaturian a real pleasure. “It was simple to find the key to performing the Concerto. The author had a perfectly clear idea of the performing plan. However, he did not restrict the performer, allowing him ample creative imagination and willingly adopted suggestions from the musicians during work on the Concerto.” Oistrakh even composed his own version of the cadenza, and Khachaturian suggested, “I am certain that you would never have written such a wonderful cadenza if you did not like my concerto. I think your cadenza is better than mine. It is a fantasy on my themes, and convincing in form. You prepare the audience very well for the reprise by providing the elements and rhythms of the first theme.”

Dmitry Shostakovich: Violin Concerto No. 2 in C-sharp Minor, Op. 129

Eugene Mravinsky, David Oistrakh and Shostakovich

In 1967, Dmitry Shostakovich prepared a 60th birthday present for Oistrakh. He writes, “Dear Dodik, I’ve finished a new violin concerto. I was thinking of you when I wrote it. I want to show you the concerto, though it’s terribly difficult for me to play these days. I’ll be very happy if the concerto pleases you, and if you’ll play it my happiness will be beyond description. If you have no objection, I’d like to dedicate the concerto to you.” Once again, Oistrakh incorporated his own revisions, and he initially tried out the work in public in the small town of Bolshevo, outside Moscow. When a tape was sent to the composer, Shostakovich exclaimed, “what a glorious interpretation.” The official premiere followed two weeks later on 26 September, with the Moscow Philharmonic under Kondrashin in the Bolshoi Hall of the Moscow Conservatory. Critics considered the new concerto “beautifully wrought and a thoroughly characteristic piece; if it makes a less immediately profound impression than its predecessor, the reason may be that the procedures of later Shostakovich are now very familiar, also that the themes themselves are perhaps of less interesting and eloquent outline than others of their kind. But their working is beautiful.”

David Oistrakh is not only remembered as one of the premier violinists of the 20th century and the creator of several violin masterpieces; he also was a wonderful human being.

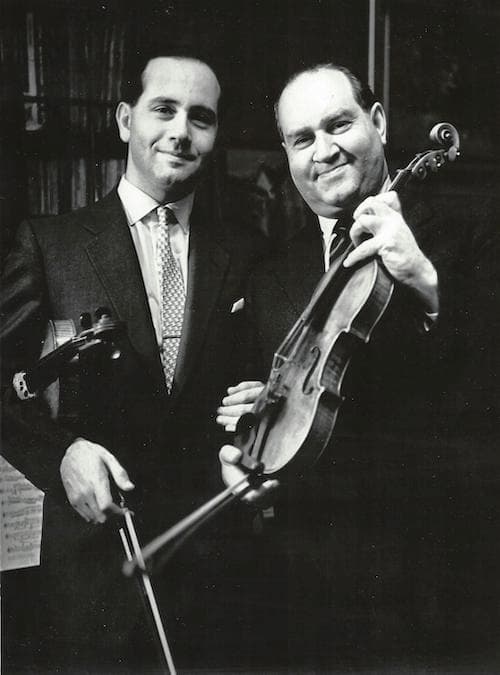

David Oistrakh and Isaac Stern

Isaac Stern remembers, “He was the gentlest of human beings, and a giant violinist. There was in his playing a beautiful control at all times, whether in fast passages or long, slow phrases. A sudden burst of virile strength and the gentle caress of a soft nuance, the smooth, sweet tone unfailingly produced at all parts of the bow, at all levels of sound, never forced, never ugly. And always that wonderful pure intonation that was invariably harmonically accurate as well. Those were the hallmarks of his playing. As for himself as a person—his life in the Soviet Union might have been expected to embitter him, yet I never once heard him utter an unkind word against a colleague, nor gossip about anyone’s failings and weaknesses. He was truly a golden man.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Dmitry Shostakovich: Sonata for Violin and Piano