Originally created as part of the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Museum of Art came to its current location in 1928 as part of a complex that now includes the Rodin Museum and The Perelman Building. The Philadelphia Museum’s collection is large and was founded on the model of London’s South Kensington Museum (now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum) to focus on applied art and science. Gifts from local collectors were important to the museum and have given it significant strengths in lace work, painting, and Old Master prints and drawings.

We’ll start with a painting of three musicians by Picasso. Created in 1921, the painting known as Nous autres musiciens (Three Musicians) was Picasso’s farewell to Cubism. The characters shown are the commedia dell’arte characters of Harlequin and Pierrot, Harlequin with a violin and Pierrot in his white hat with a woodwind instrument, and a third figure of a monk with an accordion. These figures were based on the costume designs that Picasso did for Stravinsky’s ballet Pulcinella, which was given its premiere by the Ballets Russes in Paris in 1920. Diaghilev wanted a commedia dell’arte ballet and gave Stravinsky music that, at that time, was thought to have been written by Pergolesi. This was the start of Stravinsky’s Neo-Classical period, just as much as this painting was the end of Picasso’s Cubist period and the start of his own Neo-Classical and surrealism period.

Pablo Picasso: Three Musicians, 1921 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Igor Stravinsky: Pulcinella Suite – I. Overture: Sinfonia (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

Another dance piece is this large (45 1/2 × 59 inches/115.6 × 149.9 cm) painting by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. We can’t hear the music, but we know it’s there. A note on the back says that this painting shows ‘the training of the new girls by Valentin “the Boneless.”’. Valentin le Désossé (Valentin the Boneless) was born Jacques Renaudin (1843-1907) and danced in partnership with La Goulue (shown in other Toulouse-Lautrec paintings). Désossé was distinctively tall and slender with a hawk-like nose and a prominent chin. His long arms and legs and his elasticity made him seem boneless while he was dancing, hence his nickname. Désossé was one of the few male can-can dancers and had an active following until his retirement in 1895. The painting was so indicative of the Moulin-Rouge that the owners of the establishment hung it above the bar.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance, 1889-90 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

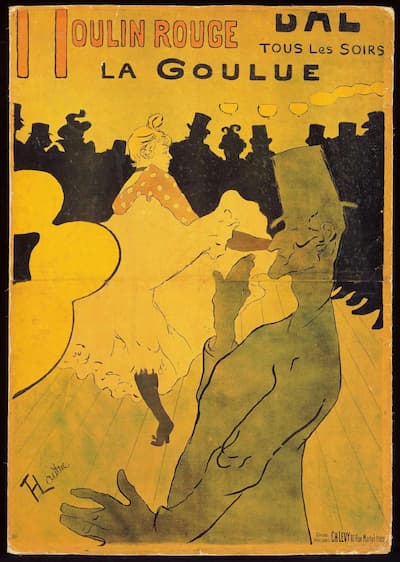

In poster advertising the new Moulin Rouge dance hall, both La Goulue (center) and Valentin (in silhouette) are shown.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: Moulin Rouge: La Goulue, 1891 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Jacques Offenbach: Orphee aux enfers (Orpheus in the Underworld) – Act II: Can-Can (Slovak State Philharmonic Orchestra, Košice; Johannes Wildner, cond.)

Monkeys in art are interesting symbols. They can remind us of our animal background, they can symbolise lascivious behaviour, they can stand for the undisciplined, or they can parody human ego and human actions. In this painting, the French artist Antoine Vollon is parodying the liberal arts: the trumpet is for music, the discarded book is for philosophy, the discarded musical score for composition, the yarn and needle for embroidery, the canvas and colours for painting, the casts at the back are for sculpture, here, Michelangelo’s designs for the Medici tombs, and there’s Minerva, the Roman goddess of the arts. But, sitting in the middle of it all, dressed in feathers and finery is a monkey, imitating a musician, imitating art, which he, as an animal, cannot create but can only imitate.

Antoine Vollon: Monkey in a Studio, 1869 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Erik Satie: Le piege de Meduse: 7 Monkey Dances – II. Valse (Olof Hojer, piano)

The great American museum collections came, for the most part, from the work of American collectors. As the nineteenth century brought increasing money to the American coffers, Americans set out across the world in search of culture that they could buy and bring home. The Musical Instrument collection at the Metropolitan Museum in New York comes from the collection of one woman, Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown, who, over a century later, remains the largest donor to that phenomenal collection. The Crosby Brown donation numbered over 3,600 pieces. Another donor, a contemporary of Brown’s, was Philadelphian Sarah Sagehorn Frishmuth. She donated some 2,000 pieces to the University of Pennsylvania Museum and along with that donation, this portrait of the donor was hung for many years. Unlike Brown, however, her collection no longer has a home but has been scattered.

Sarah Sagehorn, from Philadelphia, married her cousin William Frishmuth, who made his money in tobacco. She started her musical instrument collection while at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair before traveling to Europe for more material. Like Brown, Frishmuth focused on non-Western instruments. Frishmuth didn’t have the financial means that Brown did, but the two collectors were friendly and traded instruments with each other. Sometimes Brown commissioned Frishmuth to buy instruments on her behalf.

Frishmuth’s expertise led the Philadelphia Museum to name her honorary curator of the Department of Music Instruments in 1902. However, her collections did not survive long in Philadelphia. By 1922, the University collection had been removed from display. After her death in 1926, the Philadelphia Museum sold her collection, keeping only 2 pieces. A few choice pieces were offered to the Met Museum in New York and most of the remaining collection is now divided between the Smithsonian Institution and Yale University.

In this painting, around Frishmuth are scattered some 20 instruments from around the world, including a square piano, a peacock-shaped taus from India, a Tibetan trumpet and a Japanese drum are behind her, she holds a tenor viol, and at her feet are a cowbell, a hurdy gurdy, a lute, bagpipes, and several African instruments. On the piano are another small bagpipe, a shawm, and a serpent.

Thomas Eakins: Antiquated Music (Portrait of Sarah Sagehorn Frishmuth), 1900

(Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Franz Schubert: Winterreise, Op. 89, D. 911 – No. 24. Der Leiermann (Roman Trekel, baritone; Ulrich Eisenlohr, piano)

When Japanese screens were seen in Mexico in the late 16th century, they were an immediate hit. In this folding screen, or biomba, the artist set moral scenes based on the book Theatro moral de la vida humana (Moral Theater of Human Life) by the Dutch artist Otto van Veen (c. 1556-1629), first published in Spanish in 1669.

Here, the motto ‘Virtuoso Work Calls for Rest’ is shown using the image of Apollo playing his lyre for the 9 Muses. One Muse on the right is shown with a music book and one, facing to the back behind Apollo, seem to be holding a trumpet. Around the edge of the image are various figures in a Japanese style, with a pigtail on the right-most figure. The image, complete with Pegasus creating the spring on Mount Helicon as he struck the rock with his hoof, comes straight from van Veen.

Anonymous: Fragment from a Biombo: El Virtuoso Trabaxo pide su Reposo

(Virtuous Work Calls for Rest), c. 1740-1460 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

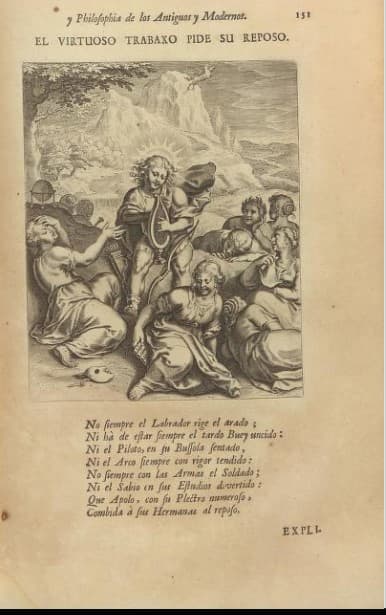

As we can see from this early 18th-century print, the image on the biombo follows the image in van Veen very closely. The text with van Veen urges the reader not to study too hard because it weakens your body and makes you tired in your spirit, warning, at the end, that many a person died too early from working too hard.

Otto van Veen: Theatro moral de la vida humana en cien emblemas. Con el Enchiridion. En Amberes: por Henrico y Cornelio Verdussen, 1701. P. 151: ‘El virtuoso trabaxo pide su reposo.’

Johannes Brahms: 5 Lieder, Op. 49 – No. 4. Wiegenlied (Lullaby) (arr. for orchestra) (Budapest Strings)

The great joke about the Baroque period is that it would have been a lot shorter if only they could have kept the lute in tune, and so we see in this painting by Theodor Rombouts of the Lute Player. The look of concentration as he turns the tuning pegs, and all the wild string ends perhaps indicating that he’s just replaced many of them, seem to indicate that he’s been working at this for a while. There are other messages here, of course, tuning an instrument could be equated with striving for a pure harmony in love. It can also symbolize temperance, particularly when we see that our lutenist has had to set aside his pipe and tankard to attend to his lute.

Theodor Rombouts: Lute Player, ca. 1620 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Nicolas Vallet: Regia pietas, hoc est: Preludium (Paul O’Dette, lute)

A lute player from a very different perspective is this poor lady who seems quite overwhelmed by her instrument. It’s very large and she can barely get her right hand around to pluck the strings. She’s also sitting at a very strange angle that seem to make it even more difficult for her to play. The setting of the house is rich – with an elaborate carpet on the table, a fine cloth over it, gold candlesticks and a silver platter with fish and another with bread. The artist, Pieter Codde, was a contemporary of Frans Hals and was known for the guardroom and group scenes, particularly those with fashionably dressed people of the day. Other Codde pictures have lutenists, most always shown in the midst of playing. What we note in this painting is the care with which the clothing has been painted – fine lace, diaphanous underdresses, velvets and gold lines.

Pieter Codde: The Lute Player, c. 1623-35 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Johann Erasmus Kindermann: Opitianischer Orpheus, Part I – No. 7. Nachtklag (Julian Prégardien, tenor; Teatro del mondo; Andrea Küppers, cond.)

Marcel Duchamp, known for his revolutionary works in conceptual art, such as his ‘Readymades’ as his bicycle wheel and the Dadaist urinal, entitled Fountain, that he submitted to an art show in 1917. He was a serious artist, as were three of his brothers. His grandfather was an artist and an engraver as well. In 1911, Duchamp created a work using his sisters as subjects. In Sonata, Yvonne is at the piano, Magdeleine is on the violin, and Suzanne sits in the foreground. Behind is their mother, Lucie. This work was Duchamp’s first attempt at Cubism, which by 1911 was in its early years in France. His controversial work of 1912, Nude Descending a Staircase, was a more complete declaration of Cubism for Duchamp, even though he had to withdraw it from the Cubist Salon des Indepéndents.

In this first work, however, he hasn’t quite gotten to Picasso’s level in terms of picturing the face at different angles, and he uses the cubist theories to break up the large planes of the frame. The piano is reduced simply to a keyboard and the violinist plays with only her bow hand. The work is quite successful, with its limited colour palette, in representing the two-part harmony of the players.

Marcel Duchamp: Sonata, 1911 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Claude Debussy: Violin Sonata in G Minor – I. Allegro vivo (Shlomo Mintz, violin; Yefim Bronfman, piano)

From Mexico to France, Philadelphia to the Netherlands, artists find a way to include music in their images, whether to show the sitter’s wide-ranging interests, to strike a mythological chord, or to represent music as a visual art. Hunting for music in the museum is a wonderful sport.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter