Franz Liszt: Hunnenschlacht

When the newly constructed “Neues Museum” (New Museum) in Berlin was looking for frescoes to illustrate the history of mankind, they turned to the painter and muralist Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1805-1874). Kaulbach had made a name for himself in Munich under the auspices of Ludwig I of Bavaria, who wanted to transform the city into a German Athens. Kaulbach designed a substantial number of frescoes for new architectural projects in the city, adorning them with scenes and allegorical figures from Greek antiquity.

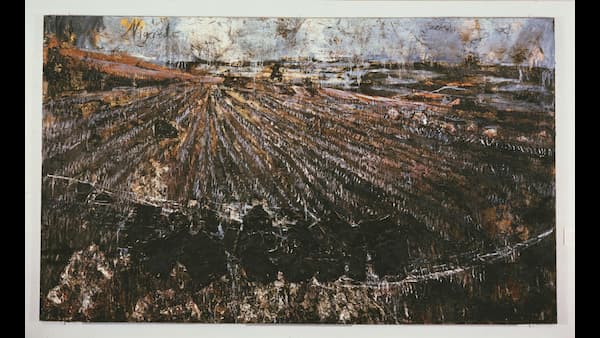

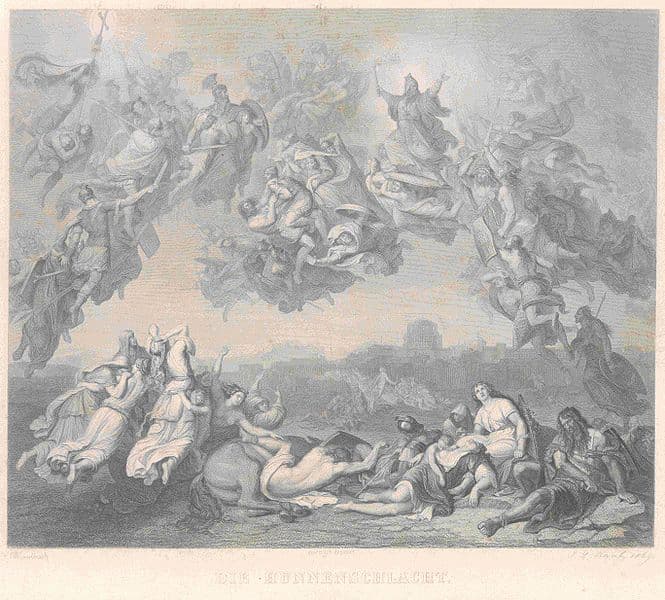

Wilhelm von Kaulbach’s Die Hunnenschlacht

The “History of Mankind” project in Berlin consisted of six frescoes, representing “The Tower of Babel,” “Homer and the Greeks,” “The Destruction of Jerusalem,” “The Battle of the Huns,” “The Crusaders at the Gates of Jerusalem,” and “The Age of the Reformation.” These major tableaux, some over 30 feet long, each comprising over one hundred above-life-size figures, are surrounded by minor compositions. The overarching narrative was to discover the prime agents of civilization in the world’s historical dramas.

Franz Liszt: Hunnenschlacht “Tempestoso” (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Gianandrea Noseda, cond.)

Portrait of Wilhelm von Kaulbach, 1864

Kaulbach’s “Battle of the Huns” is thought to depict a historical battle fought between Christians under the banner of Theodoric, the king of the Visigoths, and the Huns under king Attila. That horrifying battle did actually take place in 451 AD on the Catalaunian Fields near Troyes, and the fighting was so fierce that the spirits of those killed in battle are said to have drifted upwards towards heaven and continued the battle in the air for three days and nights.

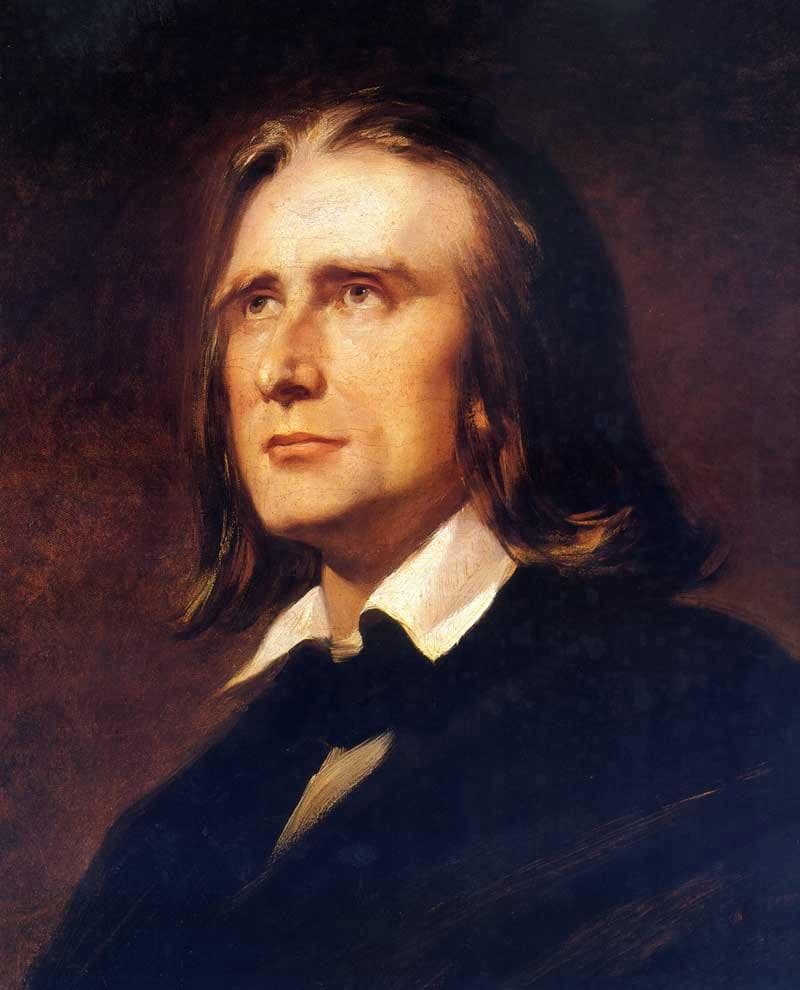

Portrait of Franz Liszt by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, 1856

While the battle of the spirits of the fallen, and the clash between civilization and barbarism, is the actual focus of Kaulbach’s painting, the battle scene is transferred to the gates of Rome. The symbol of the cross radiates light in all directions, and the ghost of the Christian leader blesses the battle scene below. Franz Liszt visited Kaulbach at his Munich studio around the end of 1856, and he immediately decided to “subject several of his historical works to musical transformation with the concept of the history of the world in music and images.”

Franz Liszt: Hunnenschlacht “Alla breve” (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Gianandrea Noseda, cond.)

Liszt shared his high opinion of Kaulbach’s work with Princess Wittgenstein. “As for Kaulbach…I do believe that he is really someone. Do tell him that I have the greatest respect and that I greatly value his friendship. When I am finished with my Dante Symphony, I shall see if I can set one of his paintings to music, Hunnenschlacht, for example…” Liszt was downright giddy when he wrote to Agnes Street-Klindworth about the project.

Steel engraving of Wilhelm von Kaulbach’s

“The princess has returned very satisfied with her artistic explorations of Berlin,” he writes. “Among other things she has brought back a beautiful sketch of Kaulbach’s Hunnenschlacht, and I feel greatly tempted to base a musical work on this sketch. That it won’t be a guitar solo goes without saying, and I shall have to set a good portion of the brass in motion.” Clearly, Liszt was already formulating the musical illustration of the painting, as he detailed some musical points. “ Use will naturally have to be made of the long pianissimo effect, with which it will be necessary to end – to leave the hearer gazing on the battle in the sky, as though terrified and dazzled by these shades unseated in combat! And I, too, sometimes feel that I am a Hun, to the very marrow of my bones. When my bones are broken and reduced to dust or decay, my spirit will breathe in the combat, the valor, and – your love!”

Franz Liszt: Hunnenschlacht “Maestoso” (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Gianandrea Noseda, cond.)

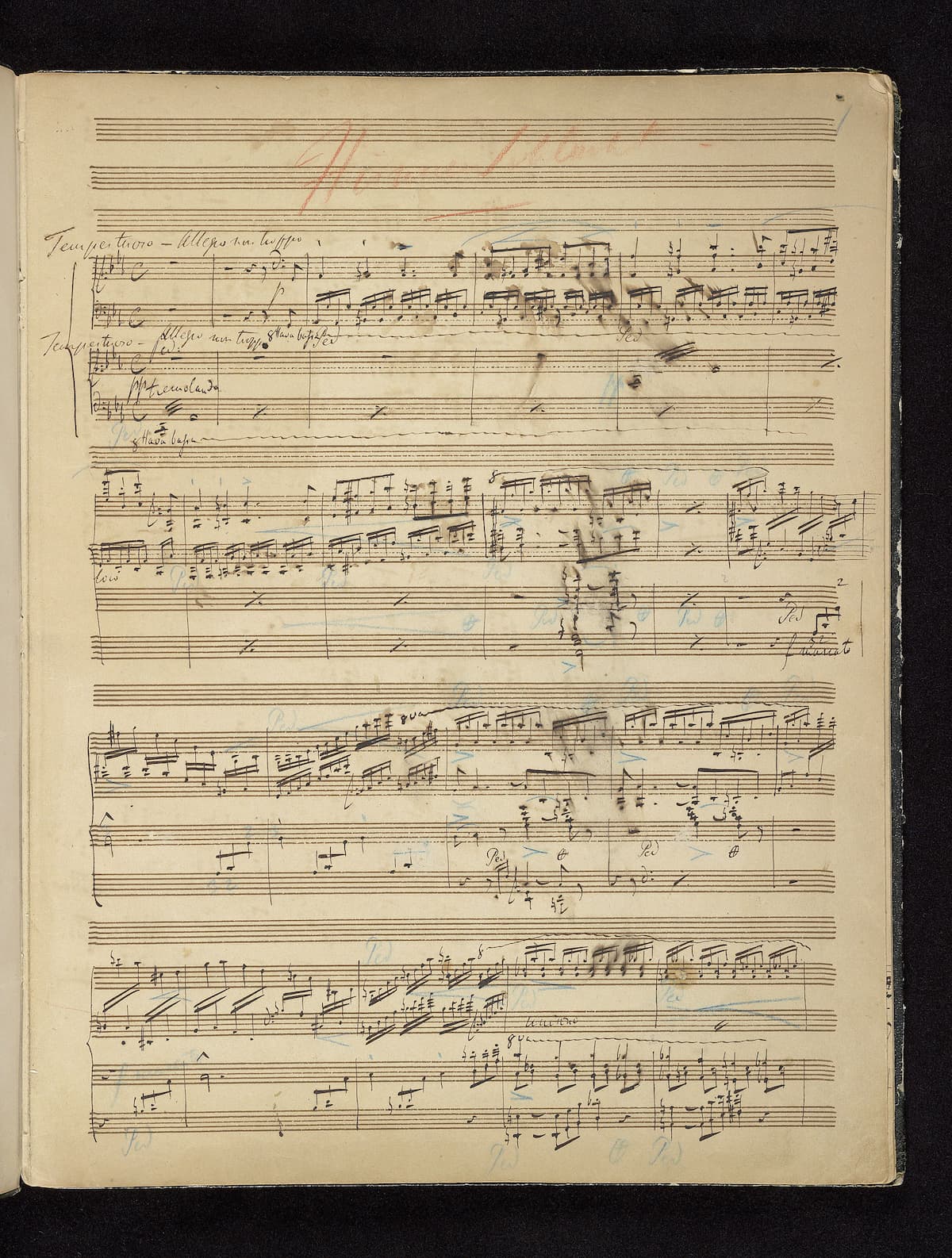

The work was completed in 1857, and on the first page of the score Liszt provided a note to the conductor that “the whole coloring must at first be very somber and all the instruments like ghosts in tone.” Referring to the Kaulbach painting in the preface to the score, Liszt writes, “it seemed to me that his idea might suitably be transferred to music and that this art was capable of reproducing the impression of the two supernatural and contrasting lights, by means of two motives, of which one should represent the fury of the barbarous passion, which drove the Huns to the devastation of so many countries and to the slaughter of so many people; while the other represents the serene powers, the virtues irradiating from Christianity. The two motives, gradually approaching each other, finish by uniting; pressing upon each other, they contend in a hand-to-hand combat like two giants, till the one which is identified with divine truth, universal charity, the progress of humanity, and hope beyond the world, is victorious and sheds over all things a radiant, transfiguring, and eternal light!”

First page of Liszt’s Hunnenschlacht manuscript

Liszt was not primarily concerned with the idea of tone painting, but as he suggested to Kaulbach’s wife, “to convey the victory of the cross in musical terms.” In his letters to Princess Wittgenstein he details two opposing shafts of light, “the one dark and troubled, the other at first radiant, later becoming softer and hazier through the Hymn of the Holy Cross.” In his powerful musical rendition of the “Battle of the Huns,” Liszt was clearly and decisively guided by the light metaphor so prevalently presented in Kaulbach’s painting.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: Hunnenschlacht “Allegro alla breve” (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Gianandrea Noseda, cond.)