When we think of J.S. Bach’s tremendous output, we never seem to consider the music that ended up in his manuscripts but which was not by him. This isn’t Bach stealing, but evidence of Bach learning. The new recording by ‘The Two Davids’, harpsichordists David Ponsford and David Hill, Bach-Centricity, brings together the works by other composers that Bach arranged, transcribed, or copied. Some of his own works are also included.

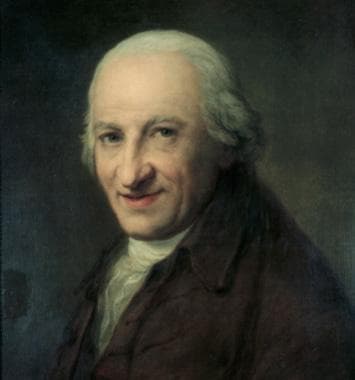

Johann Ernst Rentsch the Elder: J.S. Bach (perhaps), 1715 (Erfurt: Angermuseum)

These concertos, trios, and sonatas are evidence of the 18th-century way of education. In the land before copy machines, inexpensive reprints, and IMSLP, physically copying a work in your own hand (or giving it to your students to do) was the only way of getting a copy. We have books of music copied by J.S.’s older brother Johann Christoph Bach (in the Möller Manuscript and the Andreas Bach Book). In looking at the older Bach collection, we see more than just German music of the region; the books contain a surprising amount of French music, including Lully and Marais.

We can see from J.S.’s transcriptions that he actively sought out music from as many different countries as he could, including French, Italian, and German examples. All of the works recorded on this album carry BWV numbers.

Some of the composers on this recording include Prince Johann Ernst von Sachsen-Weimar, Antonio Vivaldi, Johann Friedrich Fasch, and François Couperin.

Johann Friedrich Fasch

Prince Johann Ernst von Sachsen-Weimar (1696–1715) studied at the University of Utrecht and furthered his music education, begun under G.C. Eilenstein, a court musician in his father’s employ. He collected music and brought it home from the Netherlands, and it is thought he might have encountered Vivaldi’s Op. 3 violin concertos during his visit. The prince was also praised for his skills as a violinist. As a composer, his works were arranged for keyboard by the court organist in Weimar, J.S. Bach. It’s unclear if the prince commissioned the transcriptions or if Bach did them as part of his personal study.

When the prince arrived home from the Low Countries, he brought so much music with him that new shelving had to be commissioned for the court library. His Concerto in F major, BWV 565, has been criticised for its lack of harmonic development, but given the youth of the composer (he died at age 19), his inexperience can be understood. Bach arranged the work for organ, and it’s been transcribed here for 2 harpsichords by David Ponsford.

J.S. Bach: Organ Concerto No. 4 in C Major, BWV 595 – III. Allegro (arr. of Concerto by Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar) (arr. D. Ponsford for 2 harpsichords) (David Hill and David Ponsford, harpsichords)

Two concertos by Antonio Vivaldi, a trio by J.F. Fasch, and the fourth section of Couperin’s L’Imperiale from Les nations, here entitled simply Aria, show the breadth of Bach’s interests.

David Ponsford

David Hill © Nick Rutter

The recording, which is essentially arrangements of arrangements, i.e., Bach transcribed the works for keyboard or for strings, and David Ponsford has made arrangements of the works for 2 harpsichords, presents the listener with a wonderful point of comparison. When all these works are re-made for the same performing forces, we can listen to them in a new way. Even Bach’s own works are arranged here for 2 harpsichords, namely, his Brandenburg Concerto No. 6. Originally written in Weimar for the old-fashioned ensemble of violas de braccio, violas da gamba, cello, and continuo, when transcribed here for 2 harpsichords, the canons in the first movement come out in a new way.

J.S. Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B-Flat Major, BWV 1051 (arr. D. Ponsford for 2 harpsichords) – I. Allegro (David Hill and David Ponsford, harpsichords)

Listening to familiar works in new arrangements brings new realisations about not only the work itself but even the compositional process. Hearing works by composers such as the prince, who have completely fallen off the map except for Bach’s hand in preserving their work, is always rewarding.

Bach-Centricity: Concertos, Trios & Sonatas arranged for Two Harpsichords

David Ponsford and David Hill, harpsichords

Nimbus Alliance: NI 6454

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter