When John Corigliano was awarded the 1999 Oscar for Best Original Score for The Red Violin, he said, “You can write all the notes you want, but if someone doesn’t play them like a god they’ll never sound that way. And Joshua Bell, the great violinist, played them like a god.” Last month in Tucson, Arizona, Joshua Bell joined his soprano wife Larisa Martínez and pianist Peter Dugan for the first performance of Corigliano’s last work, Tennessee Songs. The song cycle, based on seven poems of Tennessee Williams for soprano, violin and piano—and dedicated to Bell and Martínez—is truly music fit for the gods.

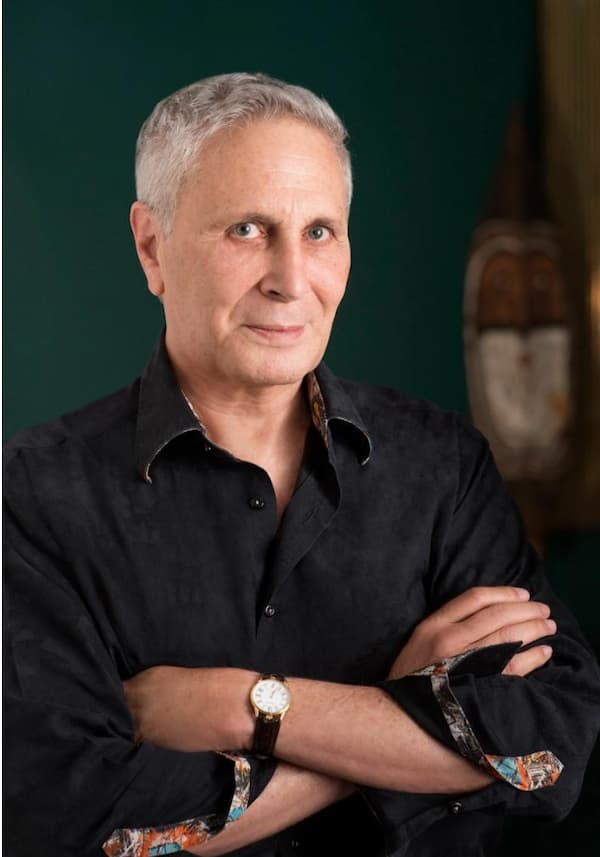

John Corigliano with Oscar from The Red Violin

John Corigliano Jr.: Violin Concerto, “The Red Violin” – I. Chaconne (Joshua Bell, violin; Baltimore Symphony Orchestra; Marin Alsop, cond.)

The commission emerged from a serendipitous idea. Jeannette Segel, president of the Tucson Desert Song Festival, and former festival director George Hanson had initially been turned down when they approached Corigliano. As Segel was attending a performance by Bell in Michigan, she envisioned music specifically for Martínez and Bell. She phoned Hanson, who coaxed along what he later called “getting the Beatles back together.” A meeting between Bell and Corigliano sealed the composer’s intent. Ultimately, Tennessee Songs was commissioned by Tucson Desert Song Festival, Arizona Friends of Chamber Music and Jeannette Segel.

![Joshua Bell and Larisa Martínez [credit Shervin Lainez]](https://interlude-cdn-blob-prod.azureedge.net/interlude-blob-storage-prod/2025/04/Joshua-Bell-and-Larisa-Martinez-credit-Shervin-Lainez.jpg)

Joshua Bell and Larisa Martínez © Shervin Lainez

Soprano Larisa Martínez sings Maria La O by Ernesto Lecuona

Corigliano’s composer husband, Mark Adamo, suggested Williams for the texts and provided the complete poems. Over lunch, Mark told me that while he made no suggestions, one of the poems Corigliano chose, Across the Space, had previously been set for mezzo-soprano, cello and piano in Adamo’s 2009 song cycle, The Racer’s Widow. The composers also shared that Adamo literally had a hand in preparing the work. The now-87-year-old Corigliano, who writes music by hand, had injured his hand before composing the songs. Adamo needed to adjust the manuscript for legibility before sending it to publisher Schirmer.

Mark Adamo © Daniel Welch

Audio of Tennessee Songs is, of course, unavailable at this time. The cycle opens with My Little One, which Corigliano describes as “a youth unaware of those who feel for him.” The song begins with a tender duet of voice and violin above a nursery-rhyme-like accompaniment. As the boy becomes a man and “runs into the burning wood,” the melody grows disjointed with anguish. The opening returns, now wistful at the pain of lost connection.

A madcap Carrousel Tune erupts with violin pyrotechnics over the line, “the freaks of the cosmic circus are men.” Is this the devil of Paganini? Saint-Saëns’ Danse Macabre? The soprano’s pinpoint leaps reinforce the windup-toy frenzy, the trio careening through it together. Melismas mourn that “love is the reason” for the madness, “but what does love do?”

Tennessee Williams in 1965 © Library of Congress

Across the Space laments the emotional distance between bed and chair: “you fade into the fading air.” Corigliano spaces melodies and chords with exquisite care, opening with a stratospheric violin above the sparest of piano chords. Voice and violin trace aching rainbows of passion, concluding in a hushed elegy.

As in many of his dramas, Tennessee Williams explores visionary madness and society’s empty response in The Beanstalk Country. Violin and voice spar with each other in wild leaps to the words, “You know how the mad come into a room, too boldly, their eyes exploding on the air like roses.” Another Rose—Williams’ sister—who was lobotomised, haunted his life. Suddenly restrained, the music weeps for the line, “They’re always attended by someone small and friendly who goes between their awful world and ours.” Then, a jolt: violin double-stops underscore, “They see not us… for they are Jacks who climb the beanstalk country… The news we bring them… cannot compete with what they have to tell.”

![Pianist Peter Dugan hosts NPR’s From the Top [credit Lisa Mazzucco]](https://interlude-cdn-blob-prod.azureedge.net/interlude-blob-storage-prod/2025/04/Pianist-Peter-Dugan-hosts-NPRs-From-the-Top-credit-Lisa-Mazzucco.jpg)

Pianist Peter Dugan hosts NPR’s From the Top © Lisa Mazzucco

Peter Dugan’s Jupiter

Sighing chords introduce Life Story with the ironic line, “After you’ve been to bed together for the first time, without the advantage or disadvantage of any prior acquaintance.” The lovers trade just as much of themselves “as time or a fair degree of prudence allows.” Both Williams and Corigliano are masters of theater; the song feels like a full operatic scene, mixing recitative with arch phrases. The violin comments slyly throughout. As the lovers drift into sleep, the piano offers a caress of gorgeously spaced chords.

In Towns Become Jewels, Williams writes: “at seven, after sunset, pearled with lamps… High, High, High is the night’s thin music above them!” How much richer his words are with Corigliano’s music! Jeweled harmonies—none functionally related, all exquisitely balanced—unfold a radiant scene. Ecstasy and harshness intertwine in a poignant farewell from a master.

Corigliano told me—as he has said publicly many times—that he works slowly. But consider his extensive body of achievements. Selecting a very few, the early Sonata for Violin and Piano (1963) won the Spoleto Festival prize for chamber music. The Symphony No. 1 (1988), composed during his residency with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, memorialised friends lost to AIDS and won the Grawemeyer Award. The Ghosts of Versailles (1991) was commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera for its 100th anniversary, the Met’s first commission since Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra. A testimony to its staying power is that Corigliano mentioned several companies that are performing it in the upcoming months. Another song cycle, Mr. Tambourine Man: Seven Poems of Bob Dylan (2000), was written without any reference to Dylan’s music.

John Corigliano Jr.: Symphony No. 1 – I. Apologue: Of Rage and Remembrance (Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Daniel Barenboim, cond.)

In a 2009 interview with American Masters on PBS, Corigliano praised Barber’s commitment to communication with audiences—but the description fits Corigliano as well: “I think one of the aspects that we have to look at is does a composer want to speak to the audience in that hall or is the composer interested in speaking to other composers at that time?” Elsewhere, he described his process: “I don’t start with music. I start with ideas. I write them down and draw maps of them, so that I really know what the piece is, just like an architect draws a blueprint.”

John Corigliano

John Corigliano Jr.: Mr. Tambourine Man: Seven Poems of Bob Dylan (version for voice and chamber ensemble) (Laura Hynes, soprano; Mary Sullivan, piccolo/flute/bass flute; Cédric Blary, clarinet/clarinet in E flat/bass clarinet; Land’s End Ensemble; Kyle Eustace, percussion; Karl Hirzer, cond.)

Corigliano’s courage to be expressive and connect with listeners couldn’t have been more evident than at the premiere of Tennessee Songs. Ripples of laughter, sighs, awe and tears swept the audience. In six decades of concertgoing, I cannot recall another premiere that held an audience so completely in thrall. I long to hear these songs again and again, once they are recorded.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter