Let’s continue to explore more concertos for unique instruments.

Einojuhani Rautavaara: Cantus Arcticus “Concerto for Birds and Orchestra,” Op. 61

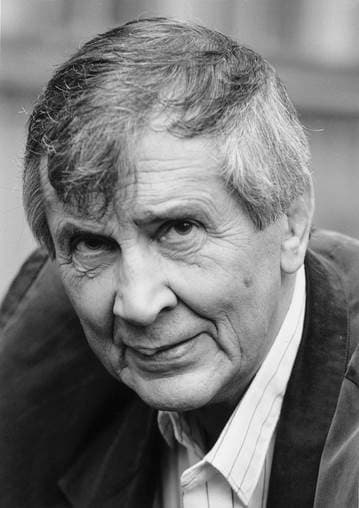

Einojuhani Rautavaara

Einojuhani Rautavaara (1928-2016) has been called “one of the most colourful and diverse figures in Finnish music. He is an artist of exceptionally broad scope, at once Romantic and intellectual, mysticist and constructivist.” He composed a number of lavish symphonies and various solo concertos, and he once remarked that his “concertos are a drama, a conflict between the individual and the collective.” That conflict takes on a special meaning in his Cantus Arcticus, subtitled “Concerto for birds and orchestra” composed in 1972. The soloists, as you can tell from the title, are actual birds, recorded near the Arctic Circle in the marshes outside the town of Iminka in northern Finland. Commissioned by the “Arctic” University of Oulu for its first doctoral degree ceremony, the entire concerto is built around a series of tape recordings featuring birds. “Like all electro-acoustic works, this piece combines the “realness” of live musical forces, in this case a chamber orchestra, with the “artifice” of electronically produced sound, in this case the tape recordings.”

The composer writes, “The first movement, “Suo” (The Marsh), opens with two solo flutes. They are gradually joined by other wind instruments and the sounds of bog birds in spring. Finally, the strings enter with a broad melody that might be interpreted as the voice and mood of a person walking in the wilds. In “Melankolia” (Melancholy), the featured bird is the shore lark; its twitter has been brought down by two octaves to make it more like a ghost bird. “Joutsenet muuttavat” (Swans migrating) features an aleatory texture with four independent instrumental groups. The texture constantly increases in complexity, and the sounds of the migrating swans are multiplied too, until finally the sound is lost in the distance.” Throughout the concerto Rautavaara calls on the instruments of the orchestra to imitate birdsong. As such, he is juxtaposing the “real” recorded voices with “live” imitations.

Paul Hindemith: Concertino for Trautonium and String Orchestra

Trautonium

Shortly after World War I, inventors in Europe, the Soviet Union and the United States competed to come up with new electronic instruments. In Germany, Friedrich Trautwein received an advanced performance degree from the Heidelberg Conservatory. He subsequently received his doctorate in engineering and acoustic from Karlsruhe Technical University in 1921. One year later, he filed a patent for a new musical instrument aptly named “Trautonium.” That instrument has been described as “an electrified cross between a violin with one string and a piano minus the keyboard.” It produces a sound akin to the blending of a flugelhorn and a saxophone. At any rate, the playing manual of the Trautonium consists of a single wire stretched over a metal plate. “When the musician presses the wire against the plate, it closes the circuit and produces a tone. Moving your finger along the wire from left to right changes the resistance and therefore the pitch, while knobs on the console further adjust the pitch. A set of movable keys lets the musician set fixed pitches.” The original Trautonium apparently generated its sound using tubes filled with neon gas, which functioned as a relaxation oscillator.

Paul Hindemith

Trautwein became a lecturer in acoustics at the Berlin Academy of Music in 1930, and his colleague Paul Hindemith was teaching music composition at the same school. They began to collaborate immediately, and Hindemith wrote music specifically for the Trautonium. The instrument first appeared in public on 20 June 1930 during a summer concert series devoted to new music. Hindemith composed a set of seven short pieces for 3 Trautonium instruments, and Hindemith, his student Oskar Sala, and the pianist Rudolf Schmidt demonstrated the potential range of the new instrument. In conjunction, Trautwein published an instruction manual as a technical guide. The Hindemith Concertino for Trautonium and String Orchestra first started with Oskar Sala as the soloist at the Radio Music Convention in Munich in 1931. Oskar Sala kept refining the instrument throughout his life, and he scored hundreds of films with his “Mixtur Trautonium,” including Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Birds.” Sadly, or luckily, the Trautonium never really caught the imagination of the public.

Paul Hindemith: Concertino for Trautonium and String Orchestra (Oskar Sala, keyboards; Munich Chamber Orchestra; Hans Stadlmair, cond.)

Jennifer Higdon: Soprano Saxophone Concerto

Soprano saxophone

Jennifer Higdon is one of America’s most acclaimed and most frequently performed living composers. She considers the sound of the oboe “to be one of the most elegant sounds in the palette of the wind family. When the opportunity came to write a concerto for this wonderful instrument, I jumped at it. As the oboe’s tone has always enchanted me, I decided that I wanted to veer from the normal style of concerto writing, where virtuosity is the primary element on display, and feature the rich tone of this double-reed instrument. To that end, this work has long sections (including the opening) that showcase its melodic gift, which alternate with 2 faster scherzi, giving the instrument’s technical speed a chance to shine.”

The Oboe Concerto was commissioned by the Minnesota Commissioning Club, and premiered by Kathy Greenbank and the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra in 2005. The work was enthusiastically received, and Higdon was soon approached by several saxophonists to arrange the Oboe Concerto for their instrument. The University of Michigan, the Hartt School, and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro underwrote that particular arrangement. The range of power and beauty that comes from saxophones had always struck Higdon. “I have seen a saxophone quartet bring a large schoolroom filled with hundreds of children to a complete halt with one single note. Many people don’t realize just how much power exists in this group of instruments, and often they may not realize the potential for beauty. The soprano saxophone in particular produces a tone of warmth and a real agility that allows it to sing like none of the other instruments in this group.”

Jennifer Higdon: Soprano Saxophone Concerto (Carrie Koffman, soprano saxophone; Hartt Wind Ensemble; Glen Adsit, cond.)

Eduard Tubin: Concerto for Balalaika and Orchestra

Eduard Tubin, 1958

Eduard Tubin (1905-1982) was born on 18 June 1905 in the village of Kallaste in Estonia. Musically talented, he was admitted to Tartu Higher Music School and started his studies in composition under the Estonian composer Heino Eller. When the Soviet Union occupied Estonia, Tubin and his family fled to Stockholm. Tubin became a Swedish citizen in 1961 and remained in Stockholm until his death in 1982. A prolific composer, Tubin wrote ten symphonies, concertos for violin, double bass, and balalaika, various chamber works, solo and choral songs, and two operas. In the early 1960, a friend of Tubin’s wife visited the family and reported that the chief doctor at Flen hospital, Nicolaus Zwetnow, was an excellent balalaika player. Tubin was asked to write something for that instrument, “but I could only wring my hand,” said Tubin. “The balalaika was not used in Estonia, and we only knew it as an instrument used in Russian entertainment music.”

Balalaika

The balalaika is indeed a Russian stringed musical instrument with a characteristic triangular wooden and hollow body. The instrument has a fretted neck and three strings, with two strings usually tuned to the same note and the third string a perfect fourth higher. Because of its short sustain, performers engage in rapid strumming or plucking when it is used to play melodies. In the event, Doctor Zwetnow was determined and he brought along his balalaika and demonstrated the capabilities of the instrument to Tubin. Finally Tubin relented, and he completed his Balalaika Concerto in 1964. Unsurprisingly, Nicolaus Zwetnow was the soloist at the premiere in 1965.

Eduard Tubin: Concerto for Balalaika and Orchestra (Emanull Sheynkman, balalaika; Swedish Radio Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Jon Lord: Concerto for Deep Purple and Orchestra

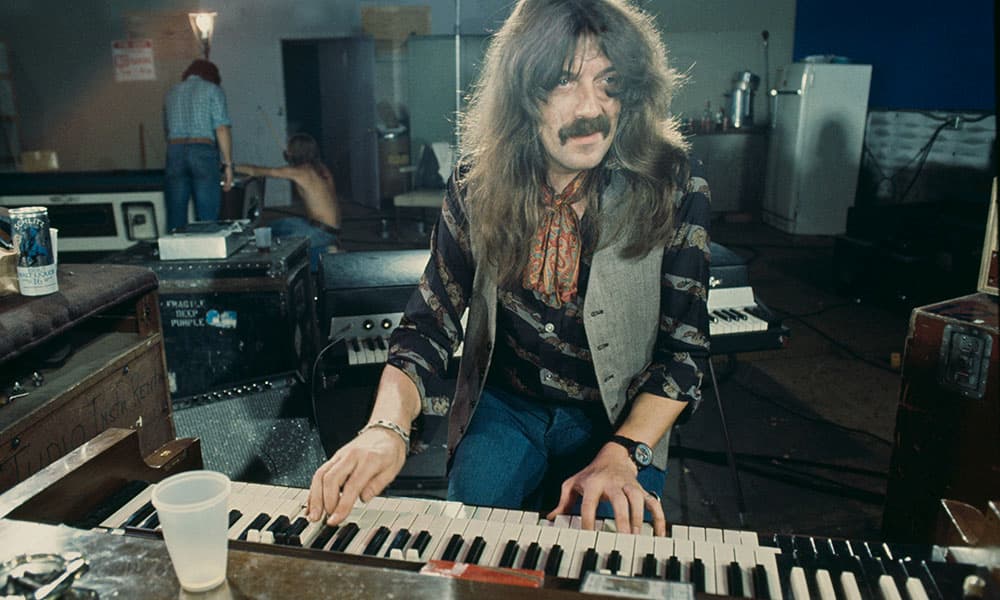

Jon Lord

More than 50 years ago, a most unusual concerto performance took place at the Royal Albert Hall in London. The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Malcom Arnold appeared on the same stage with the famed rock band “Deep Purple” in a performance of the Concerto for Deep Purple and Orchestra. It represented the first-ever combination of rock music with a full orchestra, and at that time, it arguably brought together the best conductor in the world, the best orchestra in the world and the best group in the world. This crossover premiere was the brainchild of Jon Lord, keyboardist of “Deep Purple.” The group formed in 1968, and the classic line-up brought together Ian Gillan (vocals), Roger Glover (bass guitar), Jon Lord (organ), Ritchie Blackmore (guitar), and Ian Paice (drums). Their style was influenced by Blackmore’s technique and improvisatory invention, Gillan’s vast range and vocal power, and Lord’s gospel-derived organ style.

Jon Lord (1941-2012) was born in Leicester and studied classical piano from the age of five. This classical grounding became a recurring trademark in his work, both in composition, arranging, and in his instrumental solos on piano, organ, and electronic keyboards. A constant influence in his music and keyboard improvisation was Johann Sebastian Bach, and he also drew on medieval popular music and the English tradition of Edward Elgar. The Concerto for Deep Purple and Orchestra gave “Deep Purple its first highly publicised taste of mainstream fame and it gave Lord the confidence to believe that his experiment and his compositional skill had a future.” It also allowed him to work closely with established classical figures. A second performance was given at the Hollywood Bowl in 1970, featuring the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Lawrence Foster. After that performance, the score of the work was lost. However, it has since been reconstructed, and that path-breaking concerto has played in South America, Europe and Japan in the 21st century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter