By the time he was fifteen, Franz Liszt had already begun work on what would become one of his most important early compositions; the Etude en douze exercices. This collection, first published in 1826 in both Marseille and Paris, was initially released as Opus 6 under an ambitious title promising 48 exercises in all major and minor keys. In the event, only twelve studies were actually published.

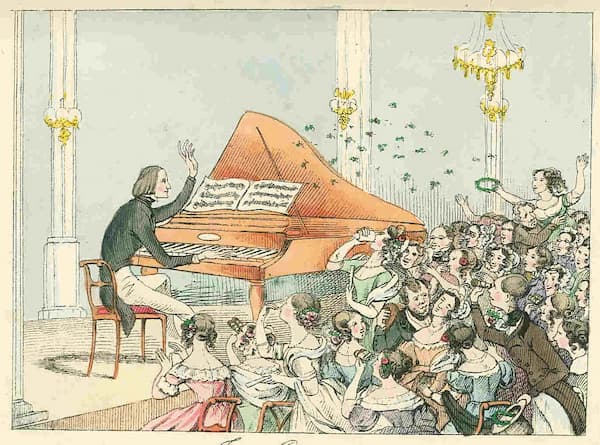

In The Concert Hall by Theodor Hosemann, 1842, caricaturing Liszt and his fans

The twelve studies from the Etude en douze exercices would later form the foundation for several revisions in Liszt’s career. In 1837, he released the Vingt-quatre grandes études (Twenty-Four Grand Studies), which, despite the title, also contained only twelve studies and was dedicated to his teacher, Carl Czerny. This set of studies, in turn, evolved into Liszt’s most famous series of piano works, the Etudes d’exécution transcendante (Studies in Transcendental Execution), which were published in 1851.

These three versions represent a progressive refinement of his compositional and technical vision. Each version builds upon the previous one, marking Liszt’s development from a young pianist-composer to a mature virtuoso while maintaining the core ambition of pushing the limits of piano technique. Let us continue our exploration of the technical and artistic evolution of Liszt’s transcendental temptations.

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 5 in B-flat Major “Moderato” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

3 Etudes in B-flat Major

Franz Liszt’s 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 5

The B-flat major Etude from 1826 is relatively straightforward. It consists of rapid arpeggios, scalar passages, and broken chords that work through a variety of modulations. The primary focus seems to be finger independence, evenness of touch, and control over rapid passages. The left hand plays an important role, as it alternates between accompaniment figures and bass notes. It is more utilitarian than deeply emotional, basically serving as a technical exercise.

When Robert Schumann compared the first version to the second, he wrote “that most of the pieces of the later work are only a revision of that youthful work which had already appeared; many, perhaps twenty years ago. In the new version, we are often uncertain whether we do not envy the boy more than the man, who seems unable to arrive at any peace!” The technical challenges of the 1837 version must have been quite puzzling to Schumann and most other pianists of the time.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 5 in B-flat Major “Egualmente” (1837) (Leslie Howard, piano)

While the structure of the B-flat Major etude of 1837 is similar to its earlier version, Liszt has significantly expanded both the complexity and depth of the piece. This version sports a virtuoso understanding of piano technique, and it demands a high level of interpretive skill. It is a devilishly difficult technical study, but it opens new interpretative possibilities in its phrasing and dynamic control.

In his final re-working as a transcendental etude, Liszt now adds the title “Feux follets” (Will-o’-the Wisp.) It opens with a rapid and delicate figuration, basically a fragment of melody heard in the middle voice. The rapid double-note passages are notoriously difficult to play, particularly as they are often asymmetrical and unpredictable. The greatest challenge, according to some pianists, is the whimsical and mysterious character implied by the title. This is particularly true in the “pianissimo” and “leggierissimo” marking around the double-note sections. The coda in the 1837 version is slightly shorter, and the double notes and repeated chords are definitely thicker and more robust.

Franz Liszt: Etudes d’exécution transcendante, No. 5 “Feux follets”

3 Etudes in G minor

Sir Hubert von Herkomer: Franz Liszt at a Piano, 1904

Compared to its later incarnation, the G-minor etude from 1826 is relatively straightforward. It primarily focuses on developing the independence of the hands and features rapid octave passages. The left hand plays a more static, rhythmic accompaniment, while the right hand executes quick arpeggios and scale-like passages. The main technical challenge lies in the coordination between both hands, as the player must maintain clarity in fast octaves and delicate passagework in the right hand.

The harmonic progressions in this early version are simple and conventional, and the music leans toward being more of an exercise than a fully realized piece of music. The phrasing and articulation, while important, are not as complex or nuanced as in the later versions, and there is less emphasis on dynamic shading or emotional expression. The work is primarily a study in evenness of tone and speed rather than a vehicle for deep musical expression.

Franz Liszt’s Étude en douze exercices, S.136 No. 6, Molto agitato

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 6 in G minor “Molto agitato” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

In his 1837 version, Liszt greatly expands upon the technical demands of the earlier etude, adding greater complexity in both hand coordination and harmonic movement. The piece now includes more independent hand motion, with the right hand often moving through complex runs and broken chords, while the left hand alternates between accompanying figures and occasional melodic lines. The use of the thumb and finger positioning becomes more central, requiring better control to navigate the wide leaps and technical passages.

Technically, the piece demands greater control of speed and precision as the runs become more intricate, requiring pianists to develop both dexterity and coordination between the hands. Liszt introduces subtle variations in the tempo and phrasing, which makes the work feel more musical, though it still retains its nature as an advanced technical study. Liszt changed the metre from duple to triple, and he pays greater attention to emotional depth by providing contrast in dynamics and phrasing.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 6 in G minor “Largo patetico” (1837) (Leslie Howard, piano)

The 1837 version resembles the final form quite closely. It is now called “Vision,” and Liszt instructed pianists to play the first three pages with the left hand alone. As in the previous version, it features various technical elements such as arpeggios, arpeggiated double notes, opposite hand movements, cantabile phrasing, leaps, and tremolos.

This etude requires fluid wrist movements and finger stretches for a singing tone. The climax includes double octaves followed by rapid right-hand arpeggios, culminating in a dramatic Ossia section. Despite its Lento tempo, the flowing and emotional quality of its long musical phrases should be maintained, with pianists emphasising accent notes in the low register.

Franz Liszt: Etudes d’exécution transcendante, No. 6 “Vision”

3 Etudes in E-flat Major

The 1826 version of the E-flat Major etude is almost classical in character. It sounds a youthful exuberance rather than the grandiose and dramatic style that would mark Liszt’s later years. There is lightness of articulation with frequent use of staccato and legato phases, and the dynamic range is more controlled.

Although a student composition, the etude already showcases some of the technical brilliance that would become a hallmark of Liszt’s style. Rapid fingerwork in the right hand is supported by broken chords or octaves. As is generally the case in this set, the E-flat Major serves as a glimpse into the early promise of Liszt’s genius.

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 7 in E-flat Major “Allegretto con molta espressione” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

Josef Danhauser: Franz Liszt Fantasizing at the Piano

Interestingly, the 1837 E-flat Major etude is widely regarded to be superior to its 1851 version. As Leslie Howard writes, “it certainly holds together better, and the transition material from the introduction to the main theme, and its repetition towards the end is altogether more convincing than the dotted rhythms which Liszt substituted in 1851. There is also a final variation of the theme, which was later cut, where again Liszt takes a very avant-garde harmonic position.”

To be sure, the 1837 version retains the essential structure from the earlier version while beginning to explore virtuosic demands. Liszt’s musical language has shifted toward greater chromaticism, a more pronounced sense of virtuosity, and an increasingly complex harmonic relationship. Yet we can clearly sense that Liszt is moving beyond technical challenges and is looking to capture a more emotionally dynamic experience.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 7 in E-flat Major “Allegro deciso” (1837) (Leslie Howard, piano)

For his Transcendental set, the E-flat Major etude now sports the title “Eroica”. On first hearing, it is more defiant than heroic, but the key of E-flat almost certainly inspired the title. It is somewhat surprising that there are no further allusions to Beethoven’s famous symphony. The “heroic” theme is introduced after some introductory chords and a blazing descending scale-passage.

The theme of the “Hero” reoccurs multiple times, and it is restated at the end. Probably the most challenging part of this etude is the double octaves that lead to the climax of the piece. This study requires rhythmic energy and precision, along with clarity and sharp attacks. The third pedal can be used to sustain the march melody while playing the surrounding chords. As a commentator wrote, “this is a march of Titans, celebrating a somewhat youthful conception of a heroism which known no doubt.”

Franz Liszt: Etudes d’exécution transcendante, No. 7 “Eroica”

3 Etudes in C minor

The C-minor Etude from 1826 is a fascinating glimpse into Liszt’s early compositional style. It is technically demanding, showcasing his ability to balance virtuosic challenges with emotional depth. While it is a product of his teenage years, it already displays many of the qualities that would define his later piano works; dramatic contrasts, harmonic exploration, and an ever-present focus on the virtuosity of the performer.

Liszt uses dramatic shifts in harmony, particularly with the use of diminished and augmented chords. These harmonic shifts provide the intensity and tension for this etude. Stormy and aggressive passages are juxtaposed by brief moments of lyrical beauty, requiring sensitivity and control from the performer.

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 8 in C minor “Allegro con spirito” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

As Leslie Howard relates, Liszt asks the impossible in the first bar of the C-minor study of 1837. “42 notes in rapid fire are asked to be held in one pedal, and yet six melody notes in each hand are asked to be accentuated. This can nearly be done on a piano of the 1830s, but Liszt wisely removed the opening flourish in the 1851 version. Nevertheless, the sheer pandemonium here and elsewhere where this theme occurs is undeniably effective.”

The 1837 version is a highly dynamic and intense work with multiple thematic sections and large contrasts in texture and dynamics. The central theme is bold and dramatic, revolving around rapid repeated notes and arpeggios, which create a dense and turbulent texture. This pianistic turbulence is contrasted by lyrical and singing lines demanding control and expressiveness. This etude is very much a product of Liszt’s penchant for technical difficulties.

Franz Liszt’s 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 8

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 8 in C minor “Presto strepitoso” (1837) (Leslie Howard, piano)

In his set of Transcendental Etudes, the C-minor study now carries the title “Wilde Jagd.” Generally, this translates to “Wild Hunt” or “Wild Chase.” It is certainly a highly challenging piece, lasting around five minutes, and it is said to portray a hunting scene from ancient mythology. Technical demands appear throughout, even in the lyrical sections where technical challenges are subtly integrated into the melody.

Some of these challenges include rapidly jumping chords, fast chromatic passages, swift arpeggios, tremolos, continuous dotted rhythms, and expansive octaves. Liszt removed striking ideas from his 1851 version. The third theme, “which follows hard upon the second, dactylic hunting motif, keeps the mere and rhythm intact in the left hand, whilst the right hand picks out a new theme with one note to its every four, but in a metre which does not square arithmetically with the left hand.” In 1851, Liszt streamlined the passage and made the melody conform to the left hand.

I trust you’ve enjoyed listening to the evolution of Liszt’s piano technique and style. Please join me for the concluding episode, coming up shortly.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter