“My Music Is Like a Garden”

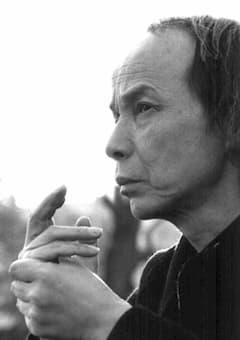

Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996), who was born in Tokyo 90 years ago, once likened his music to a walk through a garden. “I am the gardener,” he writes, “who experiences the changes in light, pattern and texture.” When I first listened closely to Takemitsu’s music, I was immediately struck by the seemingly paradoxical qualities of his expressions. For one, the music exudes an ethereal sense of space and detachment, yet he simultaneously and pointedly explores the space between objects, “an area full of energy.” Much of the complexity of his musical thought is rooted in the circumstances of his life. A month after his birth Takemitsu’s family moved to Dalian in the Chinese province of Liaoning. Once he had returned to Japan in 1938, he attended elementary school but his education was cut short by his conscription to military service in 1944. After the war he was employed at an American military base, and “fell in love with western classical music via American forces radio.” Takemitsu considered “the radio as his first real teacher.” At the age of 16 he decided, notwithstanding his lack of musical training, to take up composition.

Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996), who was born in Tokyo 90 years ago, once likened his music to a walk through a garden. “I am the gardener,” he writes, “who experiences the changes in light, pattern and texture.” When I first listened closely to Takemitsu’s music, I was immediately struck by the seemingly paradoxical qualities of his expressions. For one, the music exudes an ethereal sense of space and detachment, yet he simultaneously and pointedly explores the space between objects, “an area full of energy.” Much of the complexity of his musical thought is rooted in the circumstances of his life. A month after his birth Takemitsu’s family moved to Dalian in the Chinese province of Liaoning. Once he had returned to Japan in 1938, he attended elementary school but his education was cut short by his conscription to military service in 1944. After the war he was employed at an American military base, and “fell in love with western classical music via American forces radio.” Takemitsu considered “the radio as his first real teacher.” At the age of 16 he decided, notwithstanding his lack of musical training, to take up composition.

Tōru Takemitsu: Yume no heri e (To the Edge of Dream) (Julian Bream, guitar; City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Simon Rattle, cond.)

“Japanese traditional music became a symbol of my own bitterness.”

Tōru Takemitsu’s Requiem

His early compositions almost exclusively focused on Western musical styles and genres, as “he hated everything about Japan at that time because of his experience during the war.” For Takemitsu, “Japanese traditional music became a symbol of my own bitterness.” He experimented with electronic music technology, and became the co-founder of an artistic group that religiously avoided all references to his native Japanese artistic tradition. Relying on an explicitly modernist idiom, Takemitsu took his musical bearing from the compositions of his heroes Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. But it was a chance encounter with Igor Stravinsky that brought Takemitsu to international attention. Stravinsky visited Japan in 1958 and he heard a performance of Takemitsu’s Requiem for string orchestra. Stravinsky praised the “sincerity and passionate writing,” and he arranged for a commission of a Takemitsu work from the Koussevitsky Foundation. Dorian Horizon premiered by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Aaron Copland in 1966.

Tōru Takemitsu: Requiem (Saito Kinen Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

“I must express my deep and sincere gratitude to John Cage. ”

In the early 1960’s Takemitsu came into contact with the experimental work of John Cage and began to explore aspects of indeterminacy. In addition, Cage’s interest in Zen practices alerted Takemitsu to the potential of drawing compositional elements from the Japanese tradition. As he subsequently wrote, “I must express my deep and sincere gratitude to John Cage. The reason for this is that in my own life, in my own development, for a long period I struggled to avoid being Japanese, to avoid Japanese qualities. It was largely through my contact with John Cage that I came to recognize the value of my own tradition.” Takemitsu’s philosophy about music underwent a profound transformation as he consciously began to explore all types of traditional Japanese music. Fundamentally, it was a performance of Bunraku puppet theatre that inspired this change of heart. This art form was founded in Osaka in 1684 and features three different kinds of performers; the puppeteers, the chanters and the musicians. “I got a shock,” Takemitsu explained, “as I suddenly recognized that I was Japanese.” From then on, the composer opened his heart to the beauty of his homeland’s musical traditions. He experimented with different instruments, timbres and harmonies and evolved a highly individualistic authorial musical voice that easily transcends the implied cultural and musical duality.

In the early 1960’s Takemitsu came into contact with the experimental work of John Cage and began to explore aspects of indeterminacy. In addition, Cage’s interest in Zen practices alerted Takemitsu to the potential of drawing compositional elements from the Japanese tradition. As he subsequently wrote, “I must express my deep and sincere gratitude to John Cage. The reason for this is that in my own life, in my own development, for a long period I struggled to avoid being Japanese, to avoid Japanese qualities. It was largely through my contact with John Cage that I came to recognize the value of my own tradition.” Takemitsu’s philosophy about music underwent a profound transformation as he consciously began to explore all types of traditional Japanese music. Fundamentally, it was a performance of Bunraku puppet theatre that inspired this change of heart. This art form was founded in Osaka in 1684 and features three different kinds of performers; the puppeteers, the chanters and the musicians. “I got a shock,” Takemitsu explained, “as I suddenly recognized that I was Japanese.” From then on, the composer opened his heart to the beauty of his homeland’s musical traditions. He experimented with different instruments, timbres and harmonies and evolved a highly individualistic authorial musical voice that easily transcends the implied cultural and musical duality.

Tōru Takemitsu: November Steps (Kinshi Tsuruta, biwa; Katsuya Yokoyama, shakuhachi; Saito Kinen Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Takemitsu’s “Sea of Tonality”

Rather than favoring one musical tradition over the other, Tōru Takemitsu began to apply special attention to the differences between Western musical styles and genres, and traditional Japanese music. Above all, as he famously articulated in a lecture, he attempted to “bring forth the sensibilities of Japanese music that had always been within me.” Takemitsu’s integration of elements taken from an Eastern musical tradition with stylistic features borrowed from the West aptly reflects his belief that “various countries and cultures of the world have begun a journey toward the geographic and historic unity of all peoples. The old and new exist within me with equal weight.” Towards the end of his life Takemitsu made increased use of diatonic materials with references to tertian harmony and jazz voicing, what he called “a sea of tonality.” Takemitsu won numerous awards in his lifetime, and he published a large number of essays and other writings discussing his own works. He was a popular speaker and wrote music for more than 100 movies. He also conceived the idea of composing an opera, but died of pneumonia while undergoing treatment for cancer in 1996. Takemitsu has been honored as the most important composer in Japanese music history. “He was the first Japanese composer fully recognized in the west, and he remains the guiding light for the younger generations of Japanese composers.”

Rather than favoring one musical tradition over the other, Tōru Takemitsu began to apply special attention to the differences between Western musical styles and genres, and traditional Japanese music. Above all, as he famously articulated in a lecture, he attempted to “bring forth the sensibilities of Japanese music that had always been within me.” Takemitsu’s integration of elements taken from an Eastern musical tradition with stylistic features borrowed from the West aptly reflects his belief that “various countries and cultures of the world have begun a journey toward the geographic and historic unity of all peoples. The old and new exist within me with equal weight.” Towards the end of his life Takemitsu made increased use of diatonic materials with references to tertian harmony and jazz voicing, what he called “a sea of tonality.” Takemitsu won numerous awards in his lifetime, and he published a large number of essays and other writings discussing his own works. He was a popular speaker and wrote music for more than 100 movies. He also conceived the idea of composing an opera, but died of pneumonia while undergoing treatment for cancer in 1996. Takemitsu has been honored as the most important composer in Japanese music history. “He was the first Japanese composer fully recognized in the west, and he remains the guiding light for the younger generations of Japanese composers.”

Tōru Takemitsu: Far Calls. Coming, Far! (Michael Dauth, violin; Melbourne Symphony Orchestra; Hiroyuki Iwaki, cond.)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Thanks for making possible knowing the work of such an important composer. Beautiful pieces.