With the dramatic title of Le violon de la mort (The Violin of Death), Austrian composer Grete von Zieritz (1899–2001) shows us in the subtitle, Dances macabres, that it’s part of the long line of music written for the dead.

Grete von Zieritz, ca 1920

Dance Macabre, or Dance of Death, started in the Middle Ages as an allegory. The universality of death, particularly at a time of plagues and wars, was depicted as the final levelling of all the different orders of life: everyone from the Pope to the common labourer was stripped of their earthly finery and shown as a skeleton, each like the other. As an artwork, it appeared in murals on church walls and as illustrations in books (see below for a 15th century example from the Nuremberg Chronicle). Even when showing the universality of the dance, local artists would add local details in the body position and hand gestures, inviting the viewers to think that it could be them as the skeleton.

1920s dress-up as skeletons and skeleton horses

In the modern day, references to the dance macabre are rarer. The most well-known example is Camille Saint-Saëns’ 1874 symphonic poems of the same name, where Death on the fiddle, calls forth the dead to dance on Halloween.

Von Zieritz wrote the work in 1953 when she learned of the approaching death of her father. ‘According to her own account, she had a vision during a mountain hike: she saw the Grim Reaper in a tree and heard him playing a violin. The melody she remembered the ghoul playing became the basis of [the] work…’.

Originally written for violin and piano, the work was orchestrated in 1957, although a substantial part for the piano remained. Even later, Von Zieritz created a ballet from the music and the programmatic nature of the work was most clearly revealed. The basis is the well-known vision of death and the girl (movements 1-3), with the surprising continuation that death itself mourns its victim (movement 4) and then in sheer desperation, searches for new victims (movement 5).

Von Zieritz was born in Vienna and started studying the piano by age 6, giving her first concert at age 8. She went to Berlin to study with Martin Krause, who had been a student of Franz Liszt’s, and with Rudolf Maria Breithaupt. The success of her 1919 work, Japanese Songs, a collection of 10 songs, using texts that had been published in 1905 by Paul Anton Enderling. His translation and edition inspired von Zieritz to create a work that quickly entered the repertoire and was the impetus for her decision to achieve a career in music.

From 1926 to 1931, she studied with Franz Schreker at the Berlin Academy of Arts. In choosing music as her career and seeing little possibility of this with her home life, she left her husband and gave her daughter to her husband’s mother to raise.

Grete von Zieritz and her daughter, 1923–1924

Schreker considered her a talented composer and in 1928, was awarded two important prizes: the prestigious Mendelssohn Prize for Composition, and the Schubert Fellowship of the Columbia Phonograph Company. The fame of her teacher as a modern composer also worked to her advantage. Schreker was considered modern, but not ultra-modern, and von Zieritz was seen to hold ‘the middle ground between Brahms and Schönberg with a first-class talent.

Having no Jewish ancestors, she was able to function successfully when the National Socialists came into power. Nevertheless, von Zieritz hewed to the political line: works had traditional titles, such as the Bockelsberger Suite (1933) or Das Gifhorner Konzert (1940), and avoided some more explosive ideas she’d used earlier, such as 1930’s Passion in the Jungle. After the war, she became actively involved in the peace movement.

The first three movements, Entrée, Marche des Ombres, and Valse, take us through many different violin sounds.

We start with a highly rhythmic dance, with the marimba almost being the bones of Death (or his friends).

Michael Wolgemut: The Dance of Death, from Hartmann Schedel: Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493

Grete von Zieritz: Le violon de la mort – I. Entrée: Mit rhythmischer Vehemenz (Nina Karmon,violin; Oliver Triendl, piano; Robert Schumann Philharmonie; Jakob Brenner, cond.)

In March of the Shadows, Death has found the maiden. Her plight is described by the solo violin, while the orchestra, at first silent, then finds its voice.

Marianne Stoke: La Jeune Fille et la Mort, ca 1908 (Musée d’Orsay)

Grete von Zieritz: Le violon de la mort: II. Marche des Ombres: Nicht zu schnell! (Nina Karmon,violin; Oliver Triendl, piano; Robert Schumann Philharmonie; Jakob Brenner, cond.)

When Death dances with the Maiden, the supposed waltz is a dance that isn’t quite right. The directions say Waltz: Start slowly, somewhat gravely, but then by the end it’s all much more frightening.

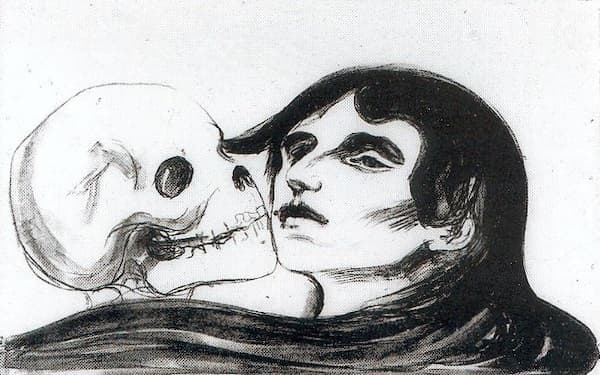

Edvard Munch: The Kiss of Death, 1899 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art)

Grete von Zieritz: Le violon de la mort – III. Valse: Langsam, etwas gravitätisch abgezirkelt beginnen! (Nina Karmon,violin; Oliver Triendl, piano; Robert Schumann Philharmonie; Jakob Brenner, cond.)

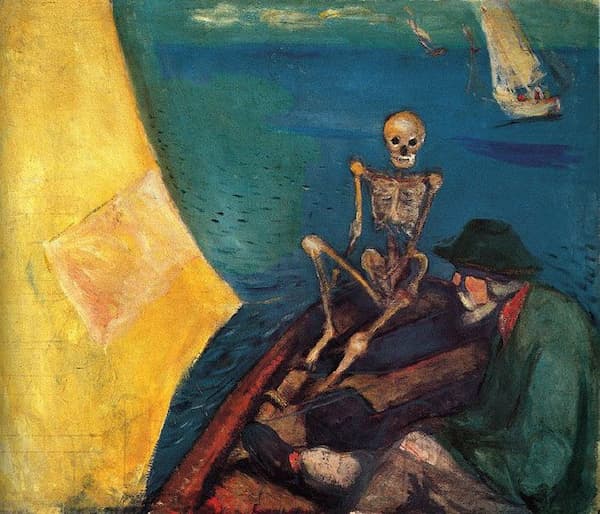

Having sent the maiden to her death, Death mourns his lost love. To be successful, however, he has to search for a new victim.

Edvard Munch: Death at the Helm, 1893 (Munch Museum)

Grete von Zieritz: Le violon de la mort – IV. Lamentation: Langsam und traurig (Nina Karmon,violin; Oliver Triendl, piano; Robert Schumann Philharmonie; Jakob Brenner, cond.)

In the final movement, with the wonderful title of Cancan phantastique, Death dances again!

José Guadalupe Posada: Don Quixote’s Skeleton, (1910-13) (Blanton Museum of Art, the University of Texas at Austin)

Grete von Zieritz: Le violon de la mort – V. Cancan phantastique: Allegro (Nina Karmon,violin; Oliver Triendl, piano; Robert Schumann Philharmonie; Jakob Brenner, cond.)

As an Austrian in West Berlin, von Zieritz was always seen as an outsider and appointments that she should have received, such as being appointed a professor of composition at the Hochschule für Musik, were not given to her. Without institutional support, she maintained her career through concerts (she was an accomplished pianist) and private teaching and her works were largely piano music and chamber works. She used the latest compositional techniques, such as serialism and micro-tonal tuning, but didn’t identify with the movements. She always sought comprehension in her music and would abandon technique (electronics, aleatoric music) when they no longer served her.

Grete von Zieritz

With the rise of the Damstadt School and composers who made their name in the post-war era, such as Stockhausen, Boulez, Ligeti and Nono, her music was no longer seen as part of the modern line, but at the same time, was not considered part of the ‘modern classical composer’ group that composers such as Schoenberg and Stravinsky inhabited. It is only now, with the new appreciation for women composers that her music is again appearing on the concert stage. Grete von Zieritz died at home in Berlin-Charlottenberg in 2001 at age 102.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter