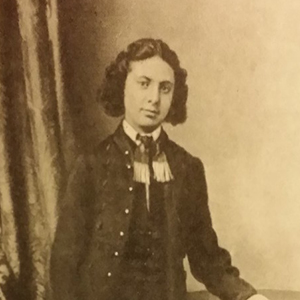

Jascha Heifetz in 1917, the year he made his American debut at Carnegie Hall

Here comes a little musical quiz question. What do Mischa Elman, Efrem Zimbalist, Nathan Milstein and Jascha Heifetz have in common? They are all famous violinists, I hear you say. And while that is certainly a correct answer, I was looking for the fact that they all were students of Leopold Auer. Auer secured the appointment as professor of violin at the St Petersburg Conservatory in 1868, and he would remain on the job for nearly a half century. His pedagogical activities shaped countless generations of exceptional musicians—apologies to hundreds of fabulous Auer students not mentioned here—and he is the rightful founder of the Russian violin school.

“He knew when to let well enough alone.” – Efrem Zimbalist

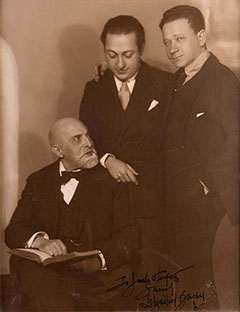

Auer with Heifetz and Zimbalist

As Auer related, “hundreds of free scholarships were available at the Conservatory, and if a really big talent came along he always had opportunity… No real violinistic genius, whom poverty might otherwise have kept from ever realizing his dreams, was deprived of his chance in life.” Most of Auer’s students came to him with their technique basically perfect. Heifetz, for example, had already played a number of concerts and even made a recording before coming to Auer. Zimbalist, who heard Heifetz before he began studying with Auer, said that Auer changed nothing fundamental about Heifetz’s playing, adding drolly: “He knew when to let well enough alone.”

“Art begins where technic ends. There can be no real art development before one’s technic is firmly established.” – Leopold Auer

Mischa Elman

Auer did not rely on a particular violin method. As he proudly proclaimed, “I have no method—unless you want to call purely natural lines of development, based on natural principles—a method.” Of course, this is a decided understatement as Heifetz credited him with teaching him “the true art of bowing,” which involved “absolute relaxation” of the bow arm and wrist. Auer suggested, for example, that students should play Bach’s Air on the G String in a slow, drawn-out manner with many counts to each note, avoiding any rigidity of the arm by holding the right elbow very high in order to let the lower arm move freely. Bach seems to have been a favorite in Auer’s teaching repertoire. “My pupils always have to play the Bach violin sonatas,” he said. “The most impressive thing about these Bach solo sonatas is they do not need an accompaniment… and they must be played as he has written them. We have the modern orchestra, the modern piano, but thank heavens, no modern violin!” For Auer, technique was purely a tool to enable interpretation. According to Auer, “I insist on a perfected technical development in every pupil who comes to me. Art begins where technic ends. There can be no real art development before one’s technic is firmly established. And a great deal of technical work has to be done before the great works of violin literature, the sonatas and concertos, may be approached.”

Bach: Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006 (Nathan Milstein, violin)

“The one great point I lay stress on in teaching is never to kill the individuality of my various pupils.” – Leopold Auer

Nathan Milstein

Heifetz said in 1918, “Auer is a wonderful and an incomparable teacher; I do not believe there is one in the world who can possibly approach him. Do not ask me just how he does it, for I would not know how to tell you.” And in a 1925 interview, Heifetz suggests, “Half an hour with Auer is always to me a great emotional and intellectual stimulus. He has a remarkable mind, a remarkable wit, a remarkable nervous system, a remarkable magnetism.” Auer stressed the individuality of his students, and as a result, they all play and sound differently. He wasn’t interested in producing a long line of “little Auers,” and once said in an interview, “The one great point I lay stress on in teaching is never to kill the individuality of my various pupils. Each pupil has his own inborn aptitudes, his own personal qualities as regards tone and interpretation. I always have made an individual study of each pupil, and given each pupil individual treatment. And always, always I have encouraged them to develop freely in their own way as regards inspiration and ideals, so long as this was not contrary to esthetic principles and those of my art… I do not believe that you can tell an Auer pupil by the manner in which he plays. And I am proud of it since it shows that my pupils have profited by my encouragement of individual development, and that they become genuine artists, each with a personality of his own, instead of violin automats.”

Fauré: Berceuse, Op. 16 (Mischa Elman, violin; Joseph Seiger, piano)

Efrem Zimbalist

As a teacher, Auer was decidedly hands-on. He always remembered his own apprenticeship with Joseph Joachim. Joachim, according to Auer, “always illustrated his meaning with bow and fiddle. But he never explained the technical side of what he illustrated. Those more advanced understood without verbal comment; yet there were some who did not.” Following into Joachim’s footsteps, Auer “could not teach by spoken explanation alone. If I have a point to make I explain it; but if my explanation fails to explain I take my violin and bow, and clear up the matter beyond any doubt. The word lives, it is true, but often the word must be materialized by action so that it’s meaning is clear.”

“Auer became like a second father to me.” – Jascha Heifetz

It has been suggested that Auer was able to produce such a stellar lineup of violinists because he was readily presented with prodigies. Yet he believed, that “every musical prodigy… has a right to be looked upon as a striking example of a pronounced natural predisposition for musical art. Of course, full mental development of artistic power must come as a result of the maturing processes of life itself.” And let’s not forget the correct manner of practicing. For Auer, “Practice should represent the utmost concentration of the brain…and during each minute of the time the brain must be as active as the fingers.” Auer set the artistic bar for his students extremely high and he was, by all accounts, a difficult teacher to please. However, for a good many of his students Auer was more than a teacher. As Jascha Heifetz proudly stated, “Auer became like a second father to me.”

Thank you for the Article about Leopold Auer. I was fortunate to study and teach at the St. Petersburg Conservatory at the classroom N 25 where Auer used to teach. And I can tell you that spirit of Leopold was there. In 2014. Started Leopold Auer Society and revoke Leopold Auer International Competition. In 2022 it will be VIII Competition. As a. musical. descendant of Leopold Auer ( 5th generation) I’ll be very happy to get more conversation with you about Leopold facts.

Please contact me if you are interested.

My name is Alla Aranovskaya and you can easily find my info in Google .

Thanks again

I was lucky enough to have had lessons from Sasha Lasserson, a very very elderly violinist and what a player, who had been taught by Leopold Auer. What a wonderful master.