Amazon Basin

The Amazon rainforest covers the majority of the Amazon basin in South America. Its region stretches over nine nations and thousands of indigenous territories, and it is said to represent over half of the planet’s remaining rainforests. Well over 30 million people of 350 different ethnic groups live in the Amazon, but the area and its people are in real trouble. In 2018, “about 17% of the Amazon rainforest was already destroyed, with large swaths of land cleared for human settlement and agriculture.” The Amazon rainforest is frequently described as the “lungs of the world,” but environmentalists are concerned that the destruction of the forest will not only lead to a loss of biodiversity, but also accelerate global warming. The area has recently experienced the worst drought in over one hundred years, and wildfires are consuming huge tracts of land in the Amazon basin. One researcher has even put a date on his predictions for the Amazon’s impending death. In 2064, so it is argued, “the Amazon rainforest will be completely wiped out.” The loss of this so-called “un-written page of Genesis,” will have a devastating effect on our planet.

Although he was born in Rio de Janeiro, the myths, legends, and vast nature of the Amazon region served as a life-long inspiration for the musical imagination of Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959).

Heitor Villa-Lobos: Uirapuru

Heitor Villa-Lobos

One of his first orchestral scores dates from 1916 and it titled Uirapuru. That title originates in an extinct Tupian language spoken by the aboriginal Tupi people of Brazil, and applies to various members of a bird family. The specific song used by Villa-Lobos is attributed to the “musician wren,” and likely based “on a transcription made during an expedition by the British botanist Richard Spruce, who published a collection of native bird melodies in 1908.” The wren is famous for its unique song, which consists of rich fluting notes intermixed with chirps and rattles. The birds can be difficult to see, but it has been celebrated in music, poetry, and even legends.

Cyphorhinus arada (Musician Wren)

Originally, Uirapuru was a short symphonic poem that got extensively reworked and expanded in 1917. The composition really came to life in 1934, however, when it was adopted for a ballet performance. The music describes an Indian-Brazilian legend of love, transformation, and loss. The small singing bird is sitting high in the trees of the rain forest, and according to local legend, it brings the magical power of love to whoever captures or kills it. A beautiful Indian maiden, so the legend goes, manages to pierce the “uirapuru” with her bow and arrow, and as the little bird falls to the ground, it transforms into a handsome young man. There is great joy among the tribesmen as the maiden guides her newfound love back toward her village, but soon an ugly old Indian, the evil spirit of the forest, boldly confronts the young couple, and with his bow and arrow shoots the young man through the heart. As he dies, the young man changes back into a bird and flies away, leaving the maiden alone and grief-stricken.

Heitor Villa-Lobos: Amazonas (Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela; Enrique Arturo Diemecke, cond.)

Tembe People of the Amazon rainforest

The tone poem Amazonas, composed originally for orchestra and published in 1917, was transcribed for piano by Villa-Lobos himself and published in a new version in 1932. Like Uirapuru, Amazonas subtitled “Brazilian Indian ballet” first appeared within the context of the newly discovered “savage art,” which took European and American concert halls by storm. The first “appearance of music of Brazil on the world stage can be dated to 1917, when the Ballets russes of Sergei Diaghilev were in Rio de Janeiro.” Raul Villa-Lobos, the composer’s father, relates the story of Amazonas.

Aerial view of the Amazon Rainforest

“A young Indian virgin, consecrated by the gods of the magic forests, had the custom of greeting the dawn and bathing in the waters of the Amazon. There she sported, calling on the sun and admiring her reflection in the waters of the river, proud in her primitive sensuality. Meanwhile the gods of the tropical winds breathed around her a gentle, perfumed breeze. Oblivious, she danced, surrendering herself to her pleasure like a simple child. Jealous and angered at this insult, the god of the winds carried the chaste perfume of the young girl to the profane region of the monsters. One of them picks up her scent from afar and, anxious to possess her, destroys everything before him, as he advances, unheard, towards her, gazing at her in ecstasy and desire. His image, however, is reflected by the sunlight on the grey shadow of the girl. Seeing her own shadow transformed, she rushes away, horrified, pursued by the monster into the abyss of her own desire.”

Violinophone

Critics have suggested that in its “stylistic originality, the ballet Amazonas signaled the emancipation of Brazilian art music from European influences, stressing the uniqueness of native Brazilian culture through an idealization of one of its greatest symbols, the mighty Amazon forest.” For Mário de Andrade, the ideological mentor of Brazilian nationalism, Amazonas was the emblem of a new Brazilian nationalist music, “written in the most daring and experimental language that Villa-Lobos had attempted so far.” It is a kaleidoscope in sound, full of rhythmic life and instrumental virtuosity. Villa-Lobos even invented a new instrument, the violinophone, featuring a horn attached to a violin. The orchestra, in the words of a critic, “crawls painfully forward, breaking branches and felling trees, tonalities and the traditional rules of composition.” As Villa-Lobos wrote, “almost all melodic material of this work was based on indigenous themes of the Amazon collected by the author. The harmonic and rhythmic atmosphere and the atmosphere created by the timbres imitate the forests, rivers, waterfalls, birds, fish and wild animals, the native forest dwellers, the caboclos (mestizos) and the legends of the Amazon basin. Its principal melodic motives are those that represent the themes of invocation, of the surprise of the mirage, the tracking and gallop of legendary monsters in the Amazon River, of the seduction, the voluptuousness and sensuality of the Indian Priestess, of the heroic songs of Indian warriors and of the rock precipice.”

Heitor Villa-Lobos: Floresta do Amazonas (Anna Korondi, soprano; São Paulo Symphony Choir; São Paulo Symphony Orchestra; John Neschling, cond.)

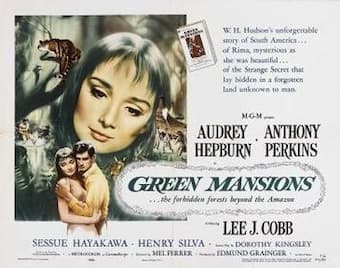

The Green Mansions film poster

In one of his last works, The Forest of the Amazon, Villa-Lobos specifically focuses on the rain forest, and the creatures and myths that live in it. This symphonic poem for soprano, male-voice choir and large orchestra originated as a commission from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for the Hollywood film “The Green Mansions,” starring Audrey Hepburn and Anthony Perkins. The film, in turn, was based on an exotic romance novel by William Henry Hudson published in 1904. It tells the story of Abel who travels into the uncharted forests of Guyana. He settles in an Indian village and discovers an enchanted forest where he hears a strange bird-like singing. He tirelessly searches for the origin of this mysterious song and finally finds Rima, the Bird Girl. As it happens, Abel falls in love with Rima, but “she is 17 and a stranger to white men and confused by odd feelings.” Their loving idyll is interspersed with birdcalls, native dances and rites, depictions of landscapes and of sunsets, hunts, chases and forest fires. In the end, Abel is taken prisoner by a hostile tribe and Rima chased up the giant tree. The natives heap brush underneath the tree and burn Rima. When Abel escapes, he finds the giant tree burned and collects Rima’s ashes. Escaping the jungle, he reaches the sea, and now as an old man, his only ambition is to be buried with Rima’s ashes. Reflecting back, he believes neither God nor man can forgive his sins, but that gentle Rima would, provided he has forgiven himself.

Bronislaw Kaper

Since Villa-Lobos had little experience with film music, he composed the score based on the screenplay by Dorothy Kingsley, believing that it was similar to writing a ballet score. He arrived in Hollywood with a finished score, which obviously didn’t synchronize with what was happening on the screen. As such, film executives told him that only a few fragments would be used, and that staff composer Bronislaw Kaper, an expert writer of film scores with a portfolio of numerous soundtracks, had been hired to compose a new score. Villa-Lobos was not amused and decided to create an independent orchestral suite, the massive Floresta do Amazonas. “With the addition of extra passages, including four orchestral songs, it is part cantata and part symphonic poem, but above all a portrait of Brazil and its forests.” In all, the suite contains twenty-three movements with such evocative titles as “In the Depths of the Forest,” “Conspiracy and War Dance,” “On the way to the Hunt,” “The Indian in Search of the Girl,” “Head Hunters,” “Forest Fire,” and numbers like “Interlude,” “Lullaby,” and “Twilight.” A master of orchestration, Villa-Lobos employs a large orchestra in a clear and elegant manner. At intervals throughout the work, a soprano returns with suggestive birdcalls clothed in lush romantic textures. A critic writes, “one senses the pulse of Brazil, not through the use of rhythms usually labeled ‘Brazilian,’ but in more subtle ways, in the use of distinctive orchestral timbres and the simplest elements that, when molded by the hands of a master, communicate the soul of his homeland.”

Philip Glass

The Amazon basin is coming under increasing environmental and human pressure. We are rapidly losing one of the world’s most important habitats and cultural resources. Its plight continues to energize ecological protests, and it fires the imagination of contemporary composers and performers. One such composer is Philip Glass, who describes himself as a composer of “music with repetitive structures.” His musical style is instantly recognizable, featuring “trademark churning ostinatos, undulating arpeggios and repeating rhythms that morph over various lengths of time atop broad fields of tonal harmony.” Although trained in the classical tradition, Glass has made intimate connections to rock, ambient music, electronic music, and world music. Glass became aware of the Brazilian instrument musical group “Uakti,” and he writes. “I saw their music and performance as a unique and beautiful contribution to the world of new and experimental music. I became friends with musicians; especially I came to admire Marco’s extraordinary ear for color and composition. I was therefore very pleased when some years later they proposed a collaboration.”

Uakti

The name “Uakti” comes from an indigenous South American legend, specifically from the Tucano people settled in the northwestern Amazon. In their mythology, “Uakti” was a fabled being living on the banks of the Rio Negro. Its body was full of holes, which, when the wind passed through them, produced sounds that bewitched the women of the tribe. The men hunted down Uakti and killed him. Palm trees sprouted up in the place where his body was buried, and the people used these to make flutes that made enchanting sounds like those produced by the body of Uakti. And just like this legendary creature, the instrumental ensemble starts with the construction of their own exotic instruments using everyday materials, like pipe, glasses, metal, rocks, rubber, and even water. “For Uakti, anything can produce sound.” The collaboration between “Uakti” and Philip Glass would be dance score for the ballet company Grupo Corpo of Belo Horizonte. Águas da Amazônia “Waters of the Amazon” draws its inspiration from the tributaries of the Amazon River. Each of the 10 movements is dedicated to one of the tributary Rivers, beginning with “Tiquié River” and flowing madly into the concluding “Metamorphosis.” Glass “once again collaborated with musicians from different traditions as the vehicle for his own creativity.” Originally, these pieces were written as piano pieces and “Uakti” brought its own creativity to the project. And that includes a couple of unique instruments like the “Flor,” made from a wooden spoon and two E-flat steel guitar strings held with nails.” Our only hopes for saving the Amazon are surely found in such international collaborations based on preservation, inspiration, ingenuity and creativity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Philip Glass: Aguas da Amazonia (Uakti)