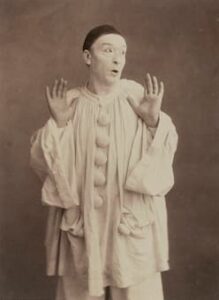

Nadar: Paul Legrand as Pierrot (1855)

In his 1912 work for voice and ensemble, Arnold Schoenberg created what has turned out to be one of the most copied small mixed ensemble in 20th century music. The group he put together for Pierrot lunaire, consisted of flute, clarinet, violin, cello, piano and percussion as players to accompany a reciter, usually a soprano.

Patricia Kopatchinskaja in Pierrot Lunaire (2019)

(Göteborgs Konserthus)

That particular ensemble was, as one composer said, ‘an orchestra in microcosm, with strings, winds, and percussion.’ In Schoenberg’s original melodrama, the instruments double: the flute also plays piccolo, the clarinet in A plays both bass clarinet and clarinet in B♭ and the violin doubles on viola.

The ensemble gives the composer the possibility of timbral color even in a small ensemble.

Arnold Schoenberg: Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21 – Part III: No. 18. The Moonspot (Christine Schäfer, narrator; Ensemble InterContemporain; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

Pierrot made its debut in 1912 and in 1913, Maurice Ravel wrote a piece for what would become to be recognized as a ‘Pierrot ensemble.’ In actuality, his instrumentation in 3 Poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé, can be argued to follow other models, such as Trois poésies de la lyrique japonaise by Stravinsky, also written in 1913, but because of the strength of Pierrot, the name stuck. The first of Ravel’s 3 Poèmes is dedicated to Igor Stravinsky.

Maurice Ravel: 3 Poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé – No. 1. Soupir (Sigh) (Jean-Christophe Benoit, baritone; Aldo Ciccolini, piano; Orchestre de Paris; Jean-Pierre Jacquillat, cond.)

In 1926, Manuel de Falla took up the ensemble for his Harpsichord Concerto. The harpsichord replaces the piano in the Pierrot ensemble. What makes this work is that the smallness of the ensemble matches the smaller sound of the harpsichord, which would have no chance against an orchestra.

Manuel de Falla: Concerto for Harpsichord, Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Violin and Cello – I. Allegro (Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord; Kraft Thorwald Dillo, flute; Horst Schneider, oboe; Sepp Fackler, clarinet; Ludwig Bus, violin; Leo Koscielny, cello)

Violinist Sarah Whitnah of the Playground Ensemble in 8 Songs for a Mad King (2019)

From these three pieces, we can start to hear how the Pierrot ensemble has a distinct sound: it may be thin in parts, but at the same time, offers a wide range of sounds.

One of the most important recent works for Pierrot ensemble was Peter Maxwell Davies’ Eight Songs for a Mad King, written in 1969. This monodrama takes as its inspiration a mechanical organ owned by King George III (the Mad King), that was used to train birds to sing. Even more than in Pierrot, the narrator performer uses extended vocal techniques to convey the king’s anguish. In a typical staging, the players are all on stage, placed in large bird cages.

Peter Maxwell Davies: 8 Songs for a Mad King – No. 1. The Sentry (King Prussia’s Minuet) (Julius Eastman, baritone; The Fires of London; Peter Maxwell Davies, cond.)

Joan Tower

Joan Tower’s Petroushskates (1980), uses the ensemble to meld the sounds of Stravinky’s Petrushka with the gliding motion of figure skating.

Joan Tower: Petroushskates (Eighth Blackbird)

Earle Brown’s 1990 work Tracking Pierrot, is described by its composer as a work that would be unique at every performance, as each entrance is cued by the conductor, rather than coming in a specific time or measure. The title comes from Brown’s acknowledgement of the instrumentation as following Pierrot and his own admiration for Schoenberg’s instrumental writing in the piece.

Earle Brown: Tracking Pierrot (Ensemble Avantegarde; Earle Brown, cond.)

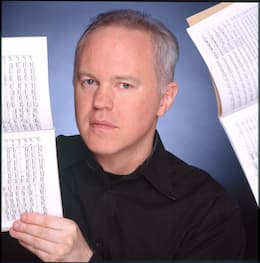

Michael Torke

Michael Torke’s 1985/1995 work Telephone Book also uses the ensemble, which he says was chosen for the practicality in getting performances more easily, for a bright shifting of sound. He notes that in his telephone book, the residential pages (The White Pages) take 133 pages to get from A to B but that the ending letter of the entries changes constantly while the first letter remains the same.

Michael Torke: Telephone Book – No. 3. The White Pages (Michael Torke, piano; Present Music Ensemble)

Robert Paterson

And so, we end up in 2019, where composer Robert Paterson used the ensemble in his four song cycles gathered under the collective title of Four Seasons. His Autumn Songs, the last to be added to his Four Seasons, he sets American poets, starting with a work by Evelyn Scott from 1920 about Central Park in late autumn as the empty tree clutch the sky and appear as skeletons, shining in the dusk.

Robert Paterson: Autumn Songs – No. 1. Ascension: Autumn Dusk in Central Park (Blythe Gaissert, mezzo-soprano; American Modern Ensemble; Robert Paterson, cond.)

It’s interesting to think of what might be considered just a miscellaneous ensemble as something that has been an inspiration for composers for over a century. Historian Paul Collaer showed why the Pierrot ensemble has proved to be such a successful model: ‘Schoenberg pointed the way for music to escape from the enormous apparatus of the great orchestra.’ Composers have continued to follow his example, each adding the potentials of the ensemble.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter