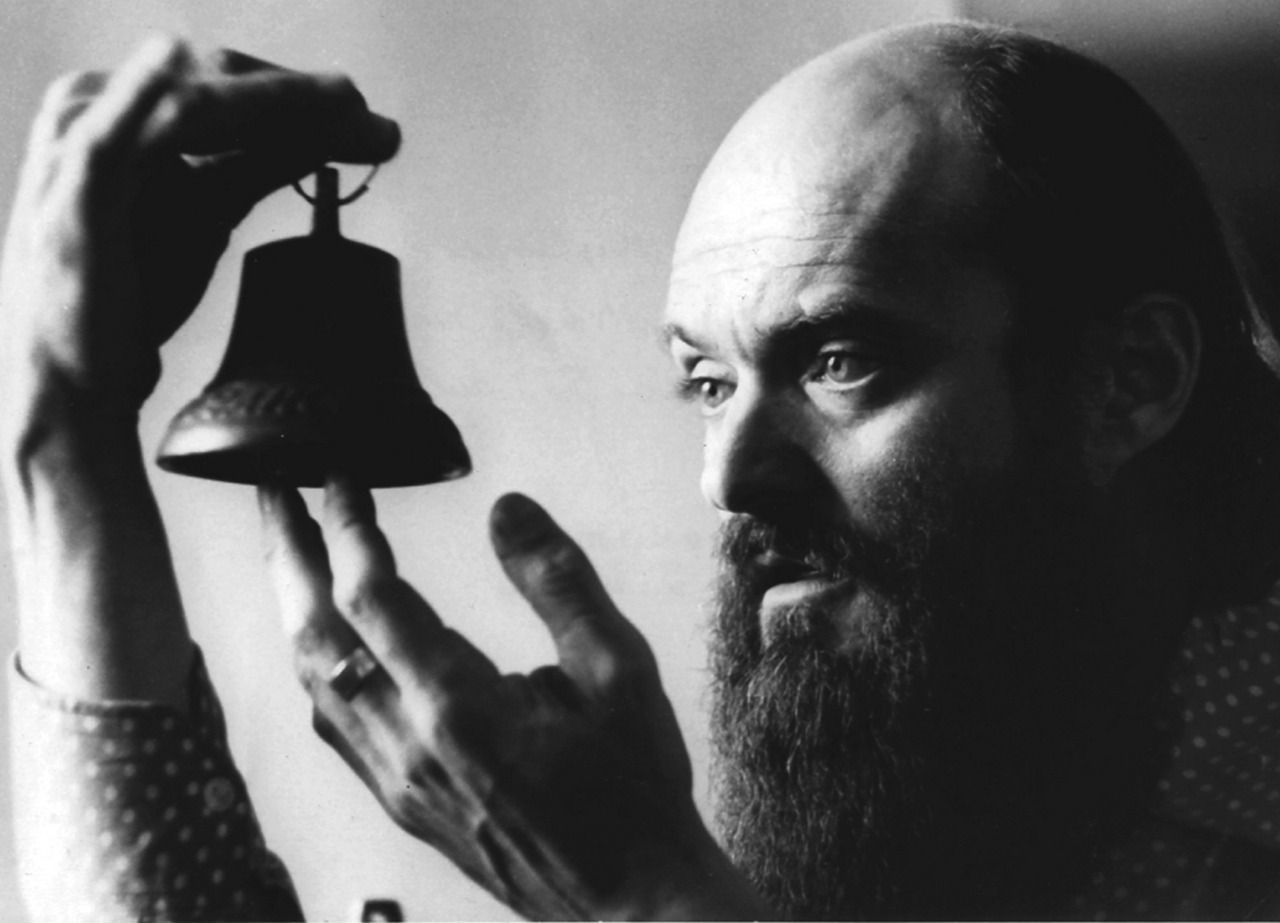

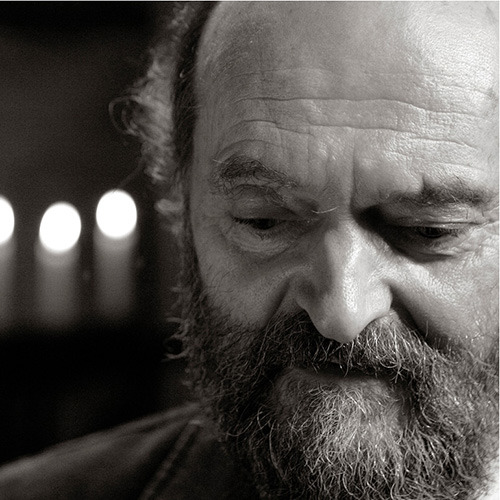

Living through the political and artistic complexities of the 20th century, Arvo Pärt always sought to communicate the spiritual power that he sees as music’s essential purpose. Initially, this quest proved rather difficult as his native Estonia was squarely placed under Soviet military and cultural authority. His earliest compositions for piano adopted the neoclassical mannerisms practiced by Shostakovich and Prokofiev. However, Pärt also began a process of directly writing for the human voice. Drawing on a text by the well-known Estonian children’s author Eno Raud, Pärt composed his cantata Meie Aed (Our Garden) for children’s choir and orchestra in 1962. Spontaneous and cheerful, the work garnered first prize at the “All-Union Young Composer’s Competition” in Moscow.

Living through the political and artistic complexities of the 20th century, Arvo Pärt always sought to communicate the spiritual power that he sees as music’s essential purpose. Initially, this quest proved rather difficult as his native Estonia was squarely placed under Soviet military and cultural authority. His earliest compositions for piano adopted the neoclassical mannerisms practiced by Shostakovich and Prokofiev. However, Pärt also began a process of directly writing for the human voice. Drawing on a text by the well-known Estonian children’s author Eno Raud, Pärt composed his cantata Meie Aed (Our Garden) for children’s choir and orchestra in 1962. Spontaneous and cheerful, the work garnered first prize at the “All-Union Young Composer’s Competition” in Moscow.

Arvo Pärt: Meie Aed (Our Garden), Op. 3

Authorities and colleagues were rather less enthusiastic with Pärt’s orchestral Nekrolog. Employing serial techniques, learned from textbooks and scores smuggled into the Soviet Union, the work was immediately at odds with the aesthetic ideals of the regime. Tikhon Khrennikov, the leader of the Union of Soviet Composers, officially renounced the “exclusive small group of composers existing in the backwater of the broad stream of musical life and engaged in formal searching and fruitless experimentation… This composition makes it quite clear that the twelve-tone experiment is untenable: ultra-expressionistic, purely naturalistic depiction of the state of fear, terror, despair and dejection.”

Arvo Pärt: Nekrolog, Op. 5

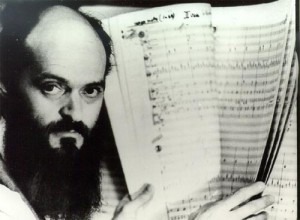

For his part, Pärt ignored the official reprimand and continued to apply serial procedures throughout the 1960’s. However, his compositions gradually became influenced by his interest in J. S. Bach. Applying collage techniques, Pärt musically projected the turmoil of Modernist dissonance against the calm order of neo-Baroque consonance. A number of works not only use the famous B-A-C-H motif, but actually employ quotes from Bach’s music as well. The Collage sur B-A-C-H is scored for strings, oboe, harpsichord and piano, and unfolds in three movements. A minimalist “moto perpetuo” gives way to a slow Bach Sarabande that is eventually demolished by aggressive clusters played on a modern piano. The major triads in the concluding “Ricercar” eventually prove more potent than all tone clusters together.

Arvo Pärt: Collage sur B-A-C-H

In Credo, composed in 1968 for mixed chorus, piano solo, and orchestra, the collage processes are pushed to their utmost limits. A grand choral opening gives way to a solo piano playing the C-major Prelude from Bach’s WTC 1. As the music becomes faster and increasingly fragmented and distorted, three worlds violently collide; the “children’s games” of the avant garde, a world of purity represented by the Bach quotation, and the setting of a religious text. Ultimately, the music returns to the Bach Prelude, now played an octave higher, for a somewhat uneasy affirmation. It was not the musical language that provoked an official scandal, however, but the avowal of Christianity.

Arvo Pärt: Credo

Trying to resolve the creative conflict he had highlighted in Credo, Pärt went into a self-imposed creative exile for the next eight years. In 1976 the composer emerged with a unique fusion of elements from Gregorian chant, harmonic simplicity, and the spiritual explorations into his Russian Orthodox faith. Please join us next time for Pärt’s music of the “little bells.”

You May Also Like

-

Infinite Reflections: Arvo Pärt’s ‘Spiegel im Spiegel’ Spiegel im Spiegel has to be the best-known of all the music by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt who is 80 this year.

Infinite Reflections: Arvo Pärt’s ‘Spiegel im Spiegel’ Spiegel im Spiegel has to be the best-known of all the music by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt who is 80 this year. - “Art has to deal with eternal Questions”

Arvo and Nora Pärt There are still celebrities who wish to keep their public and private spheres completely separate. -

Arvo Pärt Estonian-born composer Arvo Pärt (1935-) has managed to strike a sound of devotional archaism into a world of chaotic modernity.

Arvo Pärt Estonian-born composer Arvo Pärt (1935-) has managed to strike a sound of devotional archaism into a world of chaotic modernity.

More Inspiration

-

Creating a New Chopin Explore classical music's transformation in popular genres

Creating a New Chopin Explore classical music's transformation in popular genres - Reflections of the Past: George Rochberg’s Carnival Music Listen to how he blends jazz, blues, and classical quotations

- Smetana’s Musical Postcards

The Albumblätter of a Young Romantic Music composed for his wife, friends and students! - All Kinds of Elfen Kings: Schubert’s Erlkönig Transformed Explore the many faces of Schubert's 'Erlkönig' from solo violin to full orchestra