Franz Schubert (1797–1828) wrote over 600 vocal works, one of the oddest and yet most powerful of which is a ballad about a Queen, her dwarf, and a fatal encounter.

The story opens in the middle of the night: we are at sea at twilight. It’s getting dark enough that the mountains that surround the water are disappearing. In the boat are the queen and her dwarf. She looks up at the last remaining blue in the sky and speaks to the stars, accepting her fate and telling them that her death will come gladly.

Boat on foggy lake

The dwarf puts a red rope around her neck, the brightest colour in the scene, and the most fatal. The dwarf is weeping but with deadly intent. He is killing the queen because she has forsaken him for the king. The only thing that will bring him joy is her death.

He reassures her that he will hate himself forever for this act, but must do it. She hopes he will not suffer through her death, he kisses her cheeks and she dies. He sinks her deep into the sea and continues on. His heart continues to burn for her and he will never land on shore again.

The singer must control 3 voices: the narrator, the queen, and the dwarf. The narrator sets the scene: the boat, the gloom of approaching night. The queen speaks first, addressing the stars, the narrator returns, and then the dwarf speaks of his intention and his reasons for killing her. The narrator takes up the story again, to its grim end.

Franz Schubert: Der Zwerg, Op. 22, No. 1, D. 771 (Thomas Quasthoff, bass; Charles Spencer, piano)

The piano, as we would expect in Schubert, has as much a role as the singer. It sets up the first ominous chords and right-hand tremolos to show us that all is not well. There’s an urgency in the piano line that rushes us towards death. The dwarf is given an ‘obsessive four-note rhythm’ while the writing for the queen’s music is more song-like.

When the dwarf approaches the queen with his red cord, the music changes: at (01:30), with an ominous chord in the bass, the piano duplicates the dwarf’s musical line (Da trirr der Zwerg zur Königin / The dwarf goes towards the queen, drauf alsobald verghene ihr die Sinnen / and straightaway loses her senses). This duplication between the voice and piano gives an eerie focus to the critical point of the queen’s death.

The theme is morbid but Schubert’s setting is a masterpiece – the story has an inherent drama, the music sets up arcs of tension in the interaction of the two characters, and the horrified voice of the narrator who can describe but not help.

The poem was by Matthäus von Collin, tutor to Napoleon’s son, François-Charles-Joseph Bonaparte, and a leading poet and prose writer in Vienna. This poem was one of Colins’ few pieces of lyric writing (he mainly wrote historical dramas), but rated a setting by Schubert that, as we have seen, is remarkable in its power.

The poem’s original title was’ Treubruch’ (Breach of Faith) and this title appears on a copy of Schubert’s score made for Count Haugwitz. Schubert’s manuscript of the song is lost, so we don’t know if this was his original title as well or just used for the copy.

By opening the scene of poem in medias res, the pressure on the characters is already apparent. In the very first verse, the dwarf is described as a possession: ‘…die Königin mit ihrem Zwerge’ (the queen with her dwarf). He is not only someone who has admired the queen from afar but also her lover; now she has chosen the king over him and everything changes. In a sense, the world has been turned upside-down in this ballad: the dwarf is more important than the king and the illicit love the two shared was more important than that sanctioned by church and state.

The setting at twilight is also important: life (the blue sky) is overcome by darkness, just as the queen’s life is overcome by the red cord in the hands of her former lover; he sends her into shadow. The red line of death can be found in many German sources, including Goethe’s Faust and even up to Berg’s Wozzeck, where it is Wozzeck’s knife that makes the red necklace Marie wears.

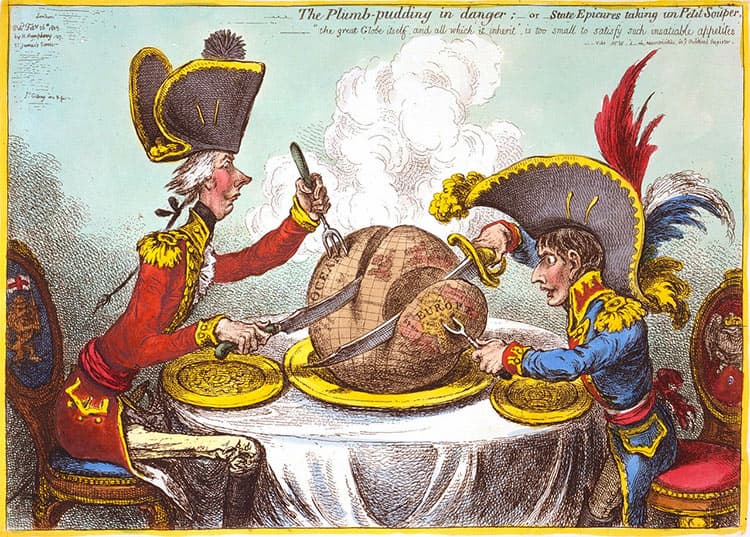

We will avoid the entire political discussion of whom the dwarf killing a queen might be but will note that Napoleon was often caricatured as a dwarf, such as in this carton by James Gillray.

Gillray: The Plumb-pudding in danger; – or – State Epicures taking un Petit Souper, 1805

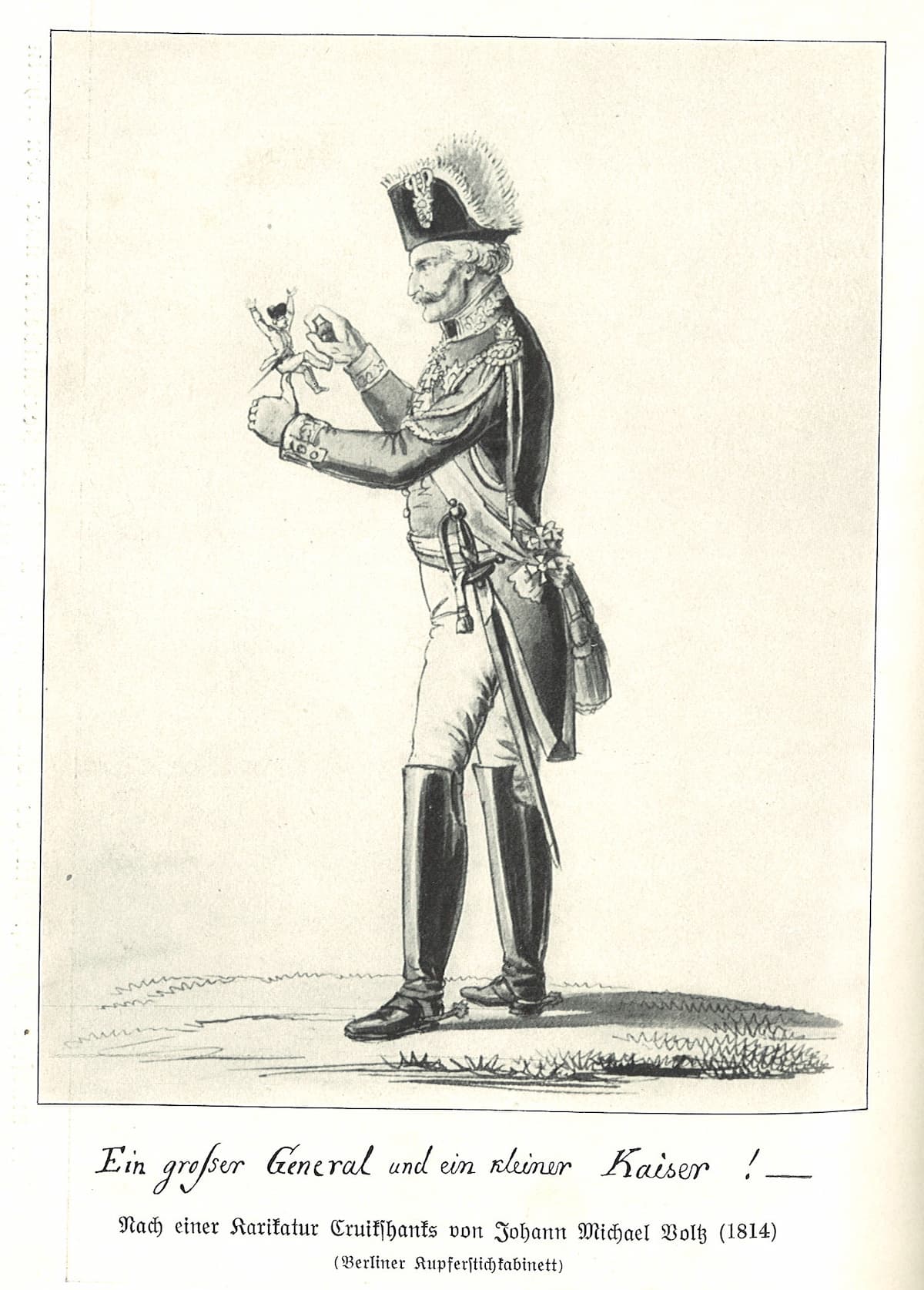

Or this German caricature of the Prussian General Blücher flicking the nose of a tiny Napoleon. At the time, Blücher was campaigning and driving back Napoleon to Paris from Russia. The Prussian Army entered Paris on 31 March 1814. The caricature post-dates the 1813 poem, but the sentiment of the dwarf emperor was common in Europe at the time.

Voltz: Ein grosser General und ein kleiner Kaiser (A Great General and a Little Emperor), 1814

We’ve gone a little astray from our tragic murder at sea, but there’s so much to question in the setting of the story that it’s an easy path into other subjects. Collins wrote his poem in the Petrarchan terza rima (3-line stanzas with interlinking rhymes: aba bcb cdc etc.). Unfortunately, German is not as flexible as Italian with a rhyme scheme like this and it’s up to Schubert to make a song out of poetry. Like his earlier Erlkönig, with its pounding urgency in the galloping horse, Schubert again uses incessant sound to make the urgency of the poem palpable. This Schicksalslied or ‘song of fate’ condemns the queen from its first sound. Note also the repeated 4-notes in the bass: short-short-short-long. That’s Beethoven’s ‘fate knocking at the door’ from his fifth symphony and cannot be incidental. Fate knocks at our poor queen, no matter how much she has accepted that the stars have determined her future.

Although Collins had a good reputation as a poet and writer, his use of terza rime made his poetic mission difficult. It was up to Schubert to see the possibilities in the story and to use music to reveal what lay behind Collins’ poem. Just as in Erlkönig, where the singer takes on the roles of the narrator, the father, the child, and the Erl-king, the use of different voices heightens the drama and makes it an audible horror story.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter