Albert Einstein is famous for having said that making mistakes is natural to seeking novelty. The musician is by nature inclined to progress, and is constantly seeking for musical improvement and development. This process is closely tied with the art of making mistakes. Effectively, this art is for the musician a way of adjusting himself and refining his skills; by doing mistakes he learns what to do—and perhaps what not to do. It is of course obvious with the composer, the performer and furthermore the improviser.

“Do not fear mistakes, there are none.”; “It’s not the note you play that’s the wrong note—it’s the note you play afterwards that makes it right or wrong”; “If you’re not making a mistake, it’s a mistake”.

Arvo Pärt

© d3i6li5p17fo2k.cloudfront.net

The preceding words are of course attributed to Miles Davis and point out the matter of relativity in making mistakes, and especially in music. Composing and performing is all about making decisions. Therefore, what makes a note correct or wrong—and what defines the mistake—is the decision the musician makes before, during and after the so-called mistake. Out of it, and in its absolute nature, there are no rights and wrongs in music.

It is all about opinion—point of views.

Sometimes the process of recognising an incorrect musical decision is immediate; with the improviser for instance. The whole purpose of improvising is to express ideas spontaneously, and often in reaction to others—therefore by means of communication. Just as when one speaks a verbal language, mistakes occur—words and sentences that should not have been said, or said differently. The improviser takes risks in playing spontaneous music. However, the improviser is constantly approaching music in an educative manner and learns from events and decisions in order to build up a stronger musical expression. This is how he improves.

At other times, the perception of the mistake comes through the—timely—distance taken from the music; with the composer for instance. When creating a piece of music, taking ownership of a bad decision often comes with time. The composer needs to reflect and take some distance from his own work. And it might take years before he realises that his musical choices could or should have been different. The advantage of a piece of work that has been written is the possibility of editing it, rearranging it or even creating new versions of it. Pärt is well-known for having re-orchestrated some of his works several times.

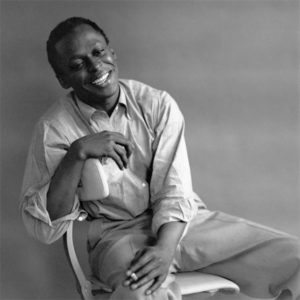

Miles Davis

© cdn8.openculture.com

Returning to the idea of relativity, what is deemed musically right and wrong; for centuries parallel fifths were perceived as musical mistakes and avoided, until composers such as Debussy broke the barrier and walls and changed its purpose—rather than being functional the parallel fifths conveyed a sensation or impression. One could say the same about dissonance, repetition, distortion etc. Today, most musicians use the mistakes and wrongs of the past as musical devices; a lot of modern music makes extensive use of dissonance and avoids using natural harmonic routes. While it was not a few centuries ago, it is now more than acceptable.

It is all about relativity.

I spent a day in a Scottish fiddle festival, starting with the youngsters and leading to the adults in the late afternoon. One feature I observed and was told about was that there were no mistakes in Scottish fiddle tunes. If a performer made a different note in a part of a performance, he or she would remember that and play the same deviation on the repeat. This attracted applause from the audience. It was 30 years ago now and I still remember that.. I suppose this is how the tunes evolved into new tunes, depending on the applause.

Amazing — such a fascinating way to approach musical evolution!