How Smetana Established the “Czechness” in His Opera

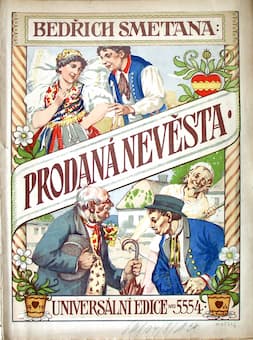

Bedřich Smetana’s “The Bartered Bride”

The Bartered Bride is a comic opera with three acts completed in 1866. It was written by Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884) with libretto by Karel Sabina (1813-1877).1 The first performance was held at the Provisional Theatre in Prague. The story is about Mařenka, a daughter from a farmer’s family, who is in love with Jeník, a son of Mícha. However, Mařenka’s parents want her to marry Mícha’s another son, Vašek. Mařenka and Jeník finally get married after overcoming the obstacles from their parents. After some revisions from the first performance, the opera was a massive success in much of Europe, including Vienna, the European capital of music. One’s national identity is based on shared geography, shared languages, and shared culture, and The Bartered Bride serves as an example of Czech music. This article will discuss how The Bartered Bride displays the Czech tradition and establishes the national identity of Czech music.

Bedřich Smetana: The Bartered Bride (Overture)

The Display of Czech Tradition

The Bartered Bride exhibits the Czech tradition through the use of language and the folk elements in the music.

1. Language

Smetana’s ‘The Bartered Bride’ presented by the Sadler’s Wells Opera Company at Sadler’s Wells, London, 1956 © Denis De Marney/Getty Images

The Bartered Bride was one of the few Czech language librettos written when Czech operas were primarily sung in German. Due to the suppression of Czechs by the Habsburg Empire in the seventeenth century, the Czech language and Protestant belief were abandoned.2 Czechs were forced to follow the rest of the Habsburg Empire to be Catholics, and German became the major language used among Czech people, especially in the cities. In 1780, the Czech language was abolished in school, and the language only survived among rural village schools and through a secret reading of the Czech bible. Most Czechs at that time, especially the people from the middle class, were “Germanized.” Czech composers like Smetana, Antonín Dvořák and Leoš Janáček were all educated in German language. The burgeoning of national identity through resuming the use of the Czech language started in the 1860s. The first independent Czech newspaper, Národní listy, was published in 1862. Additionally, in the 1860s, Czech choral societies were becoming popular.3 These choral societies drew people from different musical experiences together, and they sang music in Czech, which sometimes evoked patriotism in the singing texts. In such an environment, the Czech language in The Bartered Bride contributed to the nationalist movements in Czech lands since the nineteenth century.

2. Folk elements and characteristic dances

“The Bartered Bride” performed at the National Theatre (Prague)

© pragueexperience.com

In addition to using the Czech language, The Bartered Bride inserted folk elements representing Czech lands. For instance, Smetana composed a new polka as the opening of Act 2 and Skočná (Dance of the Comedians) in Act 3. In the revised versions, Smetana was inspired by the Czech folk dances such as Furiant (Act 2) is quoted from the folksong Sedlak, Sedlak.4 The opera also adopts characteristics suggesting other Czech hops like polka with fast duple meter and sousedská with a slow triple meter.5 The use of folk elements distances The Bartered Bride from traditional Italian and French operas while raising the profile of Czech identity.

Furiant dance in Act 2

Skočná (Dance of the Comedians)

The Establishment of Czech National Identity

The success of The Bartered Bride leads to its acceptance and recognition as the earliest Czech national opera. It introduced a trend of adaptation of folksongs in the succeeding operas. To “favor the general public,” Smetana’s other opera, The Kiss (1876), also includes folksong settings.6 Additionally, the use of chorus in strophic songs in The Bartered Bride became a popular device. Consequently, “no Czech composer until the end of the nineteenth century risked omitting the chorus.”7 The performance of The Bartered Bride in Vienna in 1892 brought models of Czech villages and included some folk costumes in the production. In less than thirty years, Smetana’s The Bartered Bride brought Czech national identity to a larger audience.

Bedřich Smetana: Dalibor – Act I: Slyšels to pøíteli, tam v nebes kùru? (Beno Blachut, tenor; Prague National Theatre Chorus; Prague National Theatre Orchestra; Jaroslav Krombholc, cond.)

Bedřich Smetana: Hubicka (The Kiss): Overture (Cleveland Orchestra; Christoph von Dohnányi, cond.)

Conclusion

The Bartered Bride is one of Smetana’s most well-known operas. As one of the earliest uses of Czech libretto, the opera also incorporates the brief quotation of folk song and the newly composed dances and strophic songs inspired by Czech folk tradition. The folk elements and strophic song chorus from The Bartered Bride established the succeeding Czech operas. In addition to that, the stage setting and costumes in the performance in Vienna further showed the “Czechness.” To conclude, The Bartered Bride was instrumental in establishing Czech national identity in the nineteenth century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

1 Karel Sabina was also the librettist for Smetana’s first opera The Brandenburgers in Bohemia.

2 The defeat from the anti-Habsburg rebellion in 1620 marked the end of Czechs’ power to be independent. See John Tyrrell, “Czech nationalism”, in Czech Opera (Cambridge University Press, 1988), 1.

3 Tyrrell, “Czech nationalism”, 5.

4 Otakar Zich was also a Czech composer, but he was more well-known as an aesthetic musicologist. The folksong Sedlak, sedlak is found in the Erben’s folksong collection. See Josef Bek, “Zich, Otakar,” in Grove Music Online, accessed 22 Nov. 2018.

5 John Tyrrell, “The Bartered Bride,” in Grove Music Online, 2002. 12 Nov. 2018.

6 Tyrrell, “Folk Elements”, 229.

7 Tyrrell, “Folk Elements”, 250.

Bibliography

Bek, Josef. “Zich, Otakar.” Grove Music Online, 2001. Accessed by 22 Nov. 2018.

Everett, William A. “Opera and National Identity in Nineteenth-Century Croatian and Czech Lands / Opera I Nacionalni Identitet U 19. Stotljeću U Hrvatskim I češkim Zemljama.” International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 35, no. 1 (2004): 63-69.

Smetana, Bedrich. The Bartered Bride, JB 1:100. Boosey and Hawkes, 1943. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cscore%7C383084.

Taruskin, Richard. 2001 “Nationalism.” Grove Music Online. 22 Nov. 2018.

Tyrrell, John. “Czech nationalism.” In Czech Opera. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Tyrrell, John. “Folk Elements and the ‘Czech Style.’” In Czech Opera. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Tyrrell, John. 2002 “Bartered Bride, The.” Grove Music Online. 12 Nov. 2018.

Tyrrell, John. 2002 “Sabina, Karel.” Grove Music Online. 12 Nov. 2018.