Women composers in the eighteenth century faced a number of obstacles to becoming composers.

At the time, music-making was widely viewed as an ornamental accomplishment for women: an ability to make them more attractive on the marriage market…not a calling to be systematically and wholeheartedly pursued.

However, two Prussian princesses, Wilhelmine (born in 1709) and Anna Amalia (born in 1723), defied expectations by taking their musical studies very seriously.

They were the sisters of renowned monarch Frederick the Great, and both women left behind a number of compositions.

Today we’re looking at their fascinating stories.

Wilhelmine of Prussia, Margravine of Brandenburg-Bayreuth (1709 – 1758)

Portrait of Wilhelmine of Prussia by Jean-Étienne Liotard

Wilhelmine was born in 1709 in Berlin. Her parents were Frederick William I of Prussia and Sophia Dorothea of Hanover.

Her birth was somewhat of a disappointment, as the royal couple – and their subjects – had been hoping for a boy.

To their relief, her brother Frederick was born three years later in 1712, fulfilling the need for a male heir.

Wilhelmine von Bayreuth (1709-1758) – Concerto â Cembalo Obligato

Wilhelmine’s childhood was traumatic. Her father was abusive, and she had a governess who beat her severely. In fact, her brother told their parents she might become paralysed if the governess wasn’t fired.

Wilhelmine used music as a coping mechanism. She began learning harpsichord when she was six.

During her nightmarish childhood, her closest companion was her musical brother Frederick. He, too, endured horrific trauma at the hands of his abusive father.

Nowadays it is believed that Frederick was queer. In 1730, he attempted to flee the court with his male lover (with Wilhelmine’s assistance), but was captured. After that desertion, he was forced to marry his wife, and his lover was beheaded in front of him.

As Frederick recovered, his close relationship with Wilhelmine was extremely important to him.

Argenore (1740) – Friederike Wilhelmine Sophie von Preußen

In 1731, she married Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, who shared her interest in music. She didn’t want to marry him, but was pressured to do so by her father in part to distract from the scandal surrounding her brother.

Initially, the marriage was happy, but after her husband took a mistress, it soured.

Wilhelmine von Bayreuth: Flute Sonata in A minor

Her husband inherited money in 1735, and the couple embarked on a construction spree, aiming to make their court one of the centers of European art. Unfortunately, that ambition nearly bankrupted the court. On the upside, though, many of their construction projects still survive today.

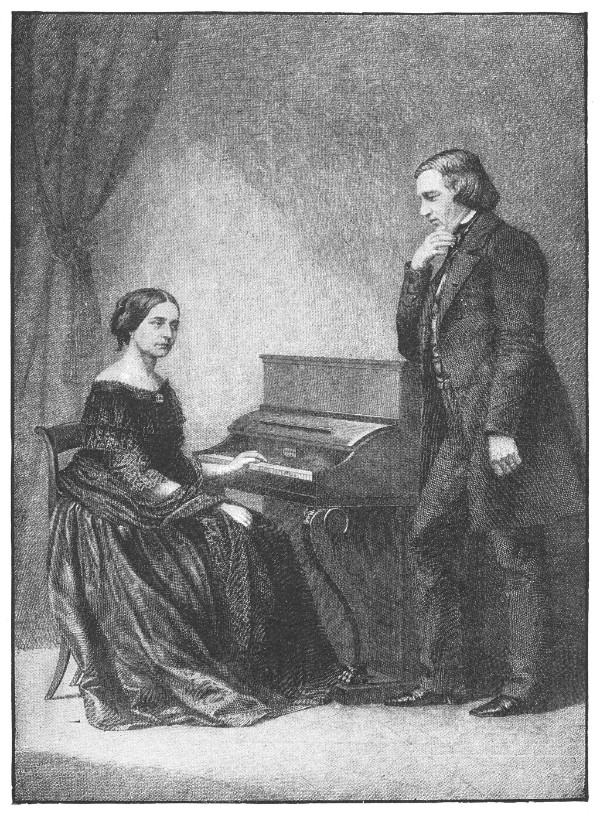

Wilhelmine with her brother Frederick, as children

During the various wars of the mid-eighteenth century, her attention turned away from art, and she became increasingly interested in diplomacy. She also wrote her memoirs.

Musically, she studied with German composer Sylvius Leopold Weiss, a contemporary of Bach’s.

She wrote an opera called Argenore (she wrote both the libretto and the score), a keyboard concerto with an obbligato flute part (both her brother and husband played the flute), and other assorted chamber music.

She died in 1758 at the age of 49.

Wilhelmine von Bayreuth – Stories: Early Women Composers

Princess Anna Amalia of Prussia (1723 – 1787)

Anna Amalia Princess of Prussia – Sonata in F major

Anna Amalia was the younger sister of Wilhelmine of Prussia.

Like her older sister, she was physically abused in childhood. When she was a little girl, her father would pull her across the room by her hair.

Even though her father disapproved of all artistic studies, she found refuge in music, just like her siblings had. In fact, her first teacher was her brother Frederick.

Portrait of Anna Amalia of Prussia

She wrote to him when she was fifteen:

“My dear brother, you know that I have been playing music for some time, and I am burning with the desire to perfect myself. Would you be so kind as to help me in this noble intention and send me some nice pieces that I could continue to practice with?”

Over time, Frederick secretly taught her the harpsichord, flute, and even the violin. The flute and violin were extremely unusual instruments for a woman to play at the time. In fact, she is one of the first female flutists that historians are aware of.

She didn’t take regular music lessons from a professional musician until she was seventeen, after the death of her father in 1740.

During this time, she would often play keyboard all day long. She also became fascinated by the organ. (Eventually she would have one built in her home.)

Anna Amalia of Prussia (1723 – 1787) – Fugue in D major

The court tried to find a politically suitable husband for Anna Amalia. However, in 1755, she was elected princess-abbess of the Free Secular Imperial Abbey of Quedlinburg. This role brought prestige, political power, and great wealth…with no marriage required.

Her social and financial position secured, she began focusing on studying music. In 1758, she hired composer Johann Kirnberger, who had been Bach’s student, and devoted herself to her art.

She took her composition studies very seriously and became a perfectionist when it came to her own compositions. It is believed that she may have burned many of her own works. However, some still survive, and it is always possible that more will come to light in future.

She especially enjoyed writing military marches: a genre that has never been thought of as particularly feminine!

Anna Amalia von Preussen (1723-87): Marche pour le régiment du Général Bülow

In addition to composing, she also collected and maintained a massive music library that was hundreds of volumes large: an impressive accomplishment in the eighteenth century.

By doing so, she helped preserve works by the Bach family, Handel, and Telemann. Without this collection, the Bach revival that occurred in the early nineteenth century likely would not have happened, or had the same impact that it ultimately did.

She died in 1787 at the age of 63.

Princess Anna Amalia of Prussia – The Virtuosa Series

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter