In 1826/27, Felix Mendelssohn published a collection of songs as his Opus 8, followed by a further collection in 1830, his Op. 9. Yet hidden in these collections are actually 6 Lieder composed by his sister Fanny Mendelssohn, published under her brother’s name. A scholar writes, “most likely, the reason her authorship was repressed was to avoid drawing unwanted public attention to the daughter of an upper-class family in such an enterprise, while still allowing her the pleasure of seeing her work made public.” We thought it was time to let Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn speak for herself, and under her own name.

Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn (Felix Mendelssohn): Zwölf Gesänge, Op. 8, No. 2 “Das Heimweh” (Lauralyn Kolb, soprano; Arlene Shrut, piano)

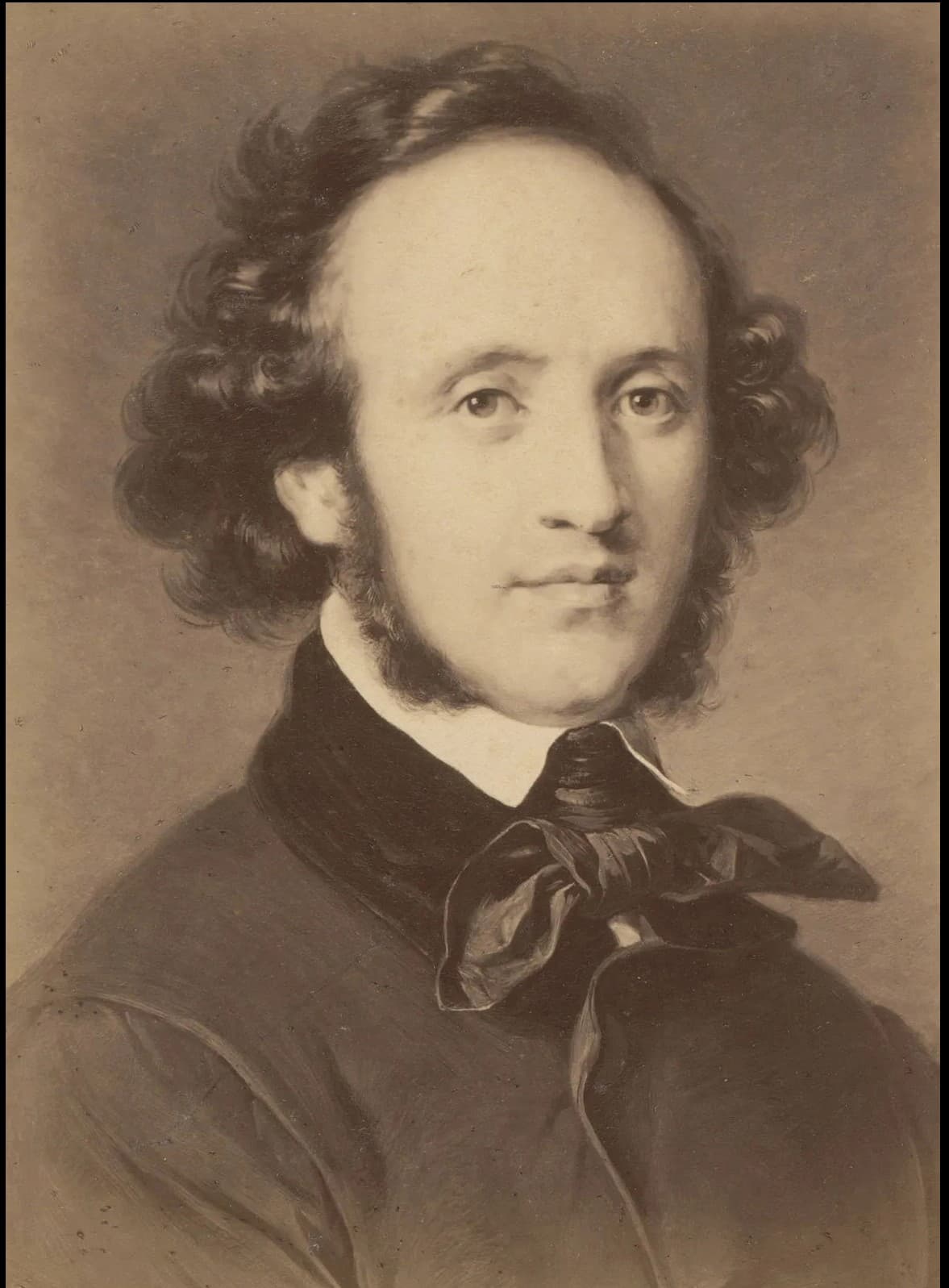

Felix Mendelssohn

“Homesickness” (trans. Sharon Krebs)

What is it that stops my breath,

And even represses the sigh?

That insinuates itself into every pathway,

And so disturbs my mind and spirit?

It is homesickness! Oh cry of pain!

Oh cry of pain, how familiar you sound within my innermost being!

What it is that robs me of my will,

Makes me discouraged about every task?

That transforms the meadow, so green and leafy,

Into a night of imprisonment?

It is homesickness! Oh sound of lamentation!

Oh sound of lamentation, how long you have already been ringing in my heart!

What is it that makes me freeze and burn,

And turns every joy and passion to gall?

Is there no word that describes it,

Is there no word in this world?

It is homesickness! Oh bitter pain!

Oh bitter pain! My home, ah! I shall never see you again!

Fanny Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg on 14 November 1805, the oldest of four children born to Abraham Mendelssohn and Lea Salomon. Fanny and her sister Rebecka had access to education and culture, and their mother placed great importance and attention on her children’s education. And although Fanny started playing the piano at a very early age, there was a strict boundary around the subject of music, “that girls should not be encouraged to take music too seriously.”

Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn (Felix Mendelssohn): Zwölf Gesänge, Op. 8, No. 3 “Italien” (Lauralyn Kolb, soprano; Arlene Shrut, piano)

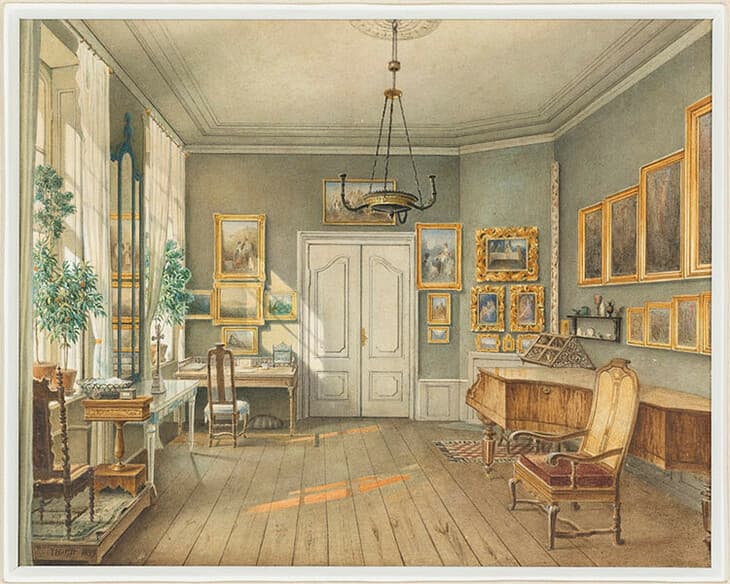

Music Room of Fanny Hensel

Felix was born four years later, and within a couple of years, the Mendelssohn family had two child prodigies on their hands. However, due to social prejudice and patriarchal mores, it was predetermined that Fanny would not become a professional musician or composer. As her father wrote to his 14-year-old daughter in 1820, “What you wrote to me about your musical occupations with reference to and in comparison with Felix was both rightly thought and expressed. Music will perhaps become his profession, whilst for you it can and must only be a feminine ornament, never the root of your being and doing.”

Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn (Felix Mendelssohn): Zwölf Gesänge, Op. 8, No. 12 “Suleika and Hatem” (Júlia Várady, soprano; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Hartmut Höll, piano)

“Suleika and Hatem”

Suleika:

By the edge of the cheerful fountain

Where streams of water play,

I did not know what was captivating me there;

But there, by your hand

My secret name was tenderly written,

I gazed down, thinking of you fondly.

Here, where the canal,

Borders the main avenue,

I look up into the cypresses

And there, once again

My letters are finely traced.

Stay fond of me!

Hatem:

May the rushing and leaping waters

And the cypresses promise:

From Suleika to Suleika

Is all my coming and my going.

For her duet setting dating from 1825, Fanny drew on a text from the “Book of Suleika” in Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan. The poem focuses on the passion between two idealized figures, “Suleika” and “Hatem,” and actually reflects Goethe’s infatuation with Marianne von Willemer. Hard as she tried, Fanny’s great effort and talent were simply not enough to overcome the inequality between the way her musical career was treated in comparison to Felix.

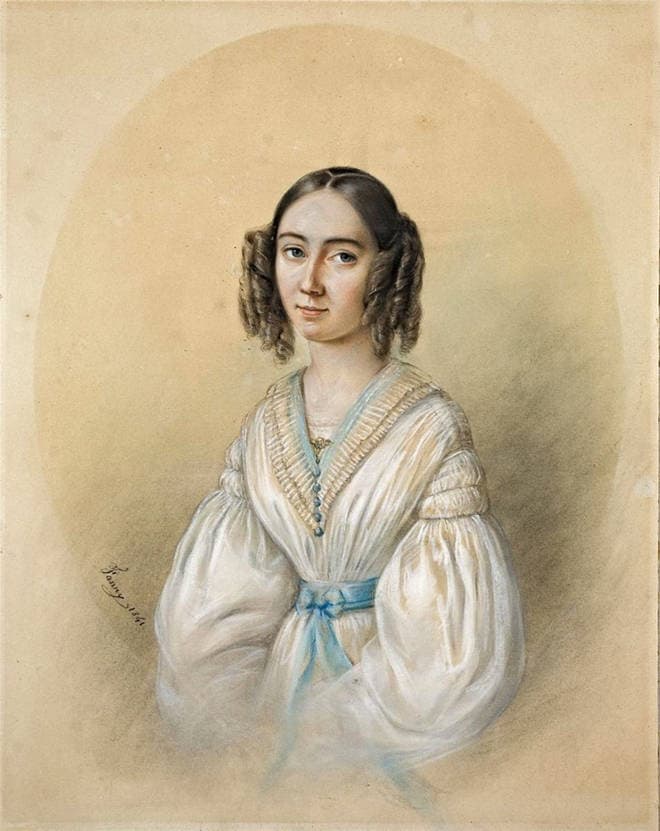

Fanny Mendelssohn

Felix strongly disapproved of Fanny performing in public and publishing her pieces, but he always did encourage his sister to keep playing and composing privately. During a tour to England in 1829, he wrote to his father that Fanny should choose which pieces of hers should be sent to the publisher Schlesinger in that year. Of course, all would be submitted and published under his own name.

Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn (Felix Mendelssohn): Zwölf Gesänge, Op. 9, No. 7 “Sehnsucht” (Lauralyn Kolb, soprano; Arlene Shrut, piano)

Felix’s motivation for including his sister’s songs in his collection and under his name has been variously interpreted. Opinion range from attributing it merely to casual disregard, “to seeing it as the active suppression of Fanny’s creative voice by her brother.” Whatever the motivation might have been, Hensel actively participated in selecting the Lieder for both opuses, and her brother openly admitted that this sister’s composition are among “the very best we possess of Lieder.”

In generally, however, Felix was squarely against that idea the Fanny should publish under her own name. As he wrote to their mother in 1837, “I cannot persuade Fanny to publish anything, because it is against my views and convictions. We have previously spoken a great deal about it, and I still hold the same opinion. I consider publishing something serious, and believe that one should do it only if one wants to appear as an author one’s entire life and stick to it. Fanny, as I know her, possesses neither the inclination nor calling for authorship. She is too much a woman, as is proper, for that, and looks after her house and thinks neither about the public nor the musical world. Publishing would only disturb her in these duties.”

Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn (Felix Mendelssohn): Zwölf Gesänge, Op. 9, No. 10 “Verlust” (Lauralyn Kolb, soprano; Arlene Shrut, piano)

“Loss” (trans. Richard Stokes)

If the little flowers knew

How deeply my heart is hurt,

They would weep with me

To heal my pain.

If the nightingales knew

How sad I am and sick,

They would joyfully make the air

Ring with refreshing song.

And if they knew of my grief,

Those little golden stars,

They would come down from the sky

And console me with their words.

But none of them can know;

My pain is known to one alone;

For she it was who broke,

Broke my heart in two.

After many years of acquiescing to her brother’s wishes, Fanny finally wrote to Felix in 1846, “I’m beginning to publish. I have finally lent a well-disposed ear to Herr Bock’s sincere professions of affection for my lieder, and to his favourable terms. And since I made the decision on my own initiative and cannot blame anyone in my family if annoying consequences result (…), then I can, on the other hand, console myself with the knowledge that I in no way sought out or occasioned the kind of musical reputation that might have brought me such offers.”

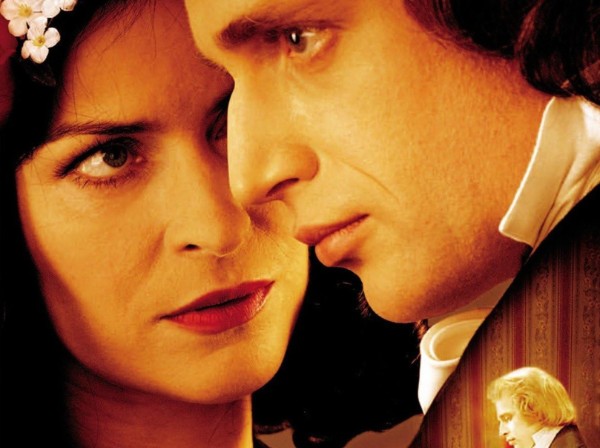

Fanny and Wilhelm Hensel

It took Felix over a month to finally respond to her letter, writing “Only today, do I, hard-hearted brother, get round to answering your kind letter and give you my professional blessing…May you know only the pleasures of being a composer, and none of the miseries.” Fanny confided in her diary that even though she knew her brother was not happy with her decision, she was pleased that he congratulated her on her published compositions.

Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn (Felix Mendelssohn): Zwölf Gesänge, Op. 9, No. 12 “Die Nonne” (Cristina Bayón Álvarez, soprano; Jesús Pineda, guitar)

“The Nun”

In the silent convent garden,

Wandered a pale maiden.

The moon shone dimly upon her.

And on her her eyelash hung

the tear of tender love.

“Well I know that my true love is dead!

I may love him once again:

for he is an angel now,

And I must worship that angel.”

She walked with timid steps to the image of the virgin Mary:

It shone in pure moonlight

And looked down so motherly and gently

Upon the pure child.

She sank down to her knees

Praying for heavenly peace

Until her eyelids closed and fell quiet in death.

Her veil fell silently to the ground.

The fact that Felix Mendelssohn’s ops. 8 and 9 also contained compositions by his sister was never a closely-guarded secret. A contemporary reviewer wrote, “one might believe the composer was a woman if one did not know the composer, if there were female composers, and if ladies could absorb such profound music.” And in a rather funny episode, Felix had to admit to Queen Victoria and Prince Consort Albert in 1842, that the Op. 8, No. 3 was composed by his sister.

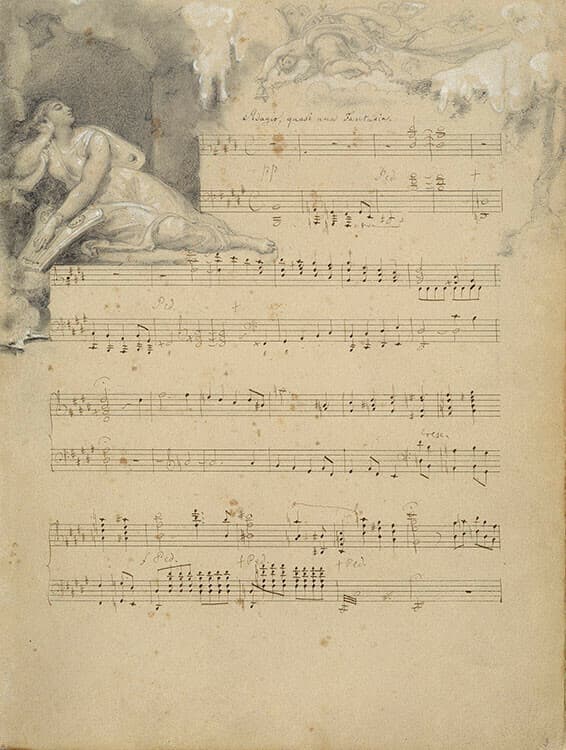

Fanny Hensel autograph vingnette by Wilhelm Hensel

Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn struggled her entire life with the conflicting impulses of authorship versus the social expectations for her high-class status… her hesitation was variously a result of her dutiful attitude towards her father, her intense relationship with her brother, and her awareness of contemporary social thought on women in the public sphere. The inclusion of her music into her brother’s collection assured that her music would never be forgotten, but it’s fair to say that her exceptional musical genius was severely stifled by societal norms and by her family. In fact, it took some 15 years from the publication of the 6 songs in her brother’s Opp. 8 and 9, to her first publication of music published under her own opus number.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn: 6 Lieder, Op. 1 (Isabel Lippitz, soprano; Barbara Heller-Reichenbach, piano)