In 1962, pianist Harriet Cohen told a story about composer Jean Sibelius on the radio.

Harriet Cohen interview from 1962

“I saw him a lot in Helsinki. I got awfully friendly with him. I used to tease him a lot, and he liked that.”

“Did you ever ask him about the mysterious eighth symphony?” the interviewer asks her.

“Well, I think that the reason… I did once tease him a bit, but I think the reason that he was so fond of me was that I didn’t ask the awkward questions. I did say when we’d been sitting up having a wonderful time with some other composers, and I said to him, ‘I don’t believe there is an eighth symphony. It’s absolutely all rot. You’re just talking about it to get attention, you see.’ And everyone roared with laughter…”

So what was the Sibelius eighth symphony all about? Why was it mysterious? Why was everyone so skeptical? And was it indeed “all rot”?

Sibelius and His Symphonies

Jean Sibelius

Symphonies were a Sibelius specialty, and much of his reputation rested on them.

His seventh symphony was completed in 1924. Today, it’s viewed as one of his great masterpieces.

It’s no surprise that expectations were high for an eighth.

Writer’s Block in the 1920s

In a September 1926 diary entry, Sibelius wrote, “I offered to create something for America.” At the time, this cryptic comment was the extent of his commentary on the subject.

In the autumn of the following year, he confessed to New York Times critic Olin Downes that he’d been making progress on a new symphony. He even claimed that he’d gotten so far as writing down the first two movements and had written the others in his head.

Unfortunately, by 1928, his hopes had faded. He began the year by writing to his wife that the new symphony would be “wonderful.” However, by December, a Danish publisher inquired after the eighth, and Sibelius confessed he hadn’t yet written anything down at all.

Koussevitzky Steps In

Serge Koussevitzky

In 1930, a protracted back-and-forth began with Serge Koussevitzky, the music director of the Boston Symphony, to whom he’d promised his eighth symphony.

In January, he was elusive. He couldn’t “say when it [would] be ready.” By August, he promised a score by the spring of 1931.

Then, in the summer of 1931, Sibelius made an announcement: the symphony was almost ready to be sent to the printers. Koussevitzky was ecstatic, and he took out an article in the Boston Evening Transcript advertising the premiere. Sibelius responded to that by saying the symphony wouldn’t be ready after all.

This frustrating game of cat and mouse continued through 1933, at which point Koussevitzky gave up. He gave a cycle of Sibelius symphonies, whose highlight was meant to be the premiere of the eighth symphony. The cycle came and went, with no eighth symphony.

So Was Sibelius Writing Anything At All?

It’s enough to make one wonder if Sibelius had written anything at all! And yet his diary and correspondence with his wife Aino prove he must have.

In May 1931, he wrote to her about the progress he was making, and his diaries reveal tantalizing clues. He said that the new work was “romantic” and “like coming home” and that working on it made him feel “full of youth. How can this be explained?”

A genuine breakthrough seems to have occurred in the summer of 1933 when Sibelius hired his copyist to make a fair copy of the first movement.

Sibelius suggested to him that what he’d copied out was only one-eighth of what was to come. The implications were staggering. If those proportions held, this last symphony would be his longest. The myth continued to grow.

Writer’s Block in the 1930s

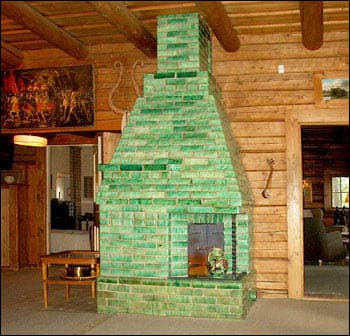

Fireplace in Sibelius’ home

But time passed with no updates, and contradictory reports began emerging from the composer himself.

In 1935, Sibelius gave an interview in which he stated he had recently discarded a year’s worth of work. It must have made his listeners’ hearts drop.

During this time, he was paralyzed by self-doubt. His daughter wrote, “He wanted it to be better than the other symphonies. Finally, it became a burden, even though so much of it had already been written down. In the end, I don’t know whether he would have accepted what he had written.”

World War and Burning Manuscripts

Stress brought on by the combined force of World War II and the Winter War between the Soviet Union and Finland put a damper on his creativity. Sibelius wrote that current events were keeping him awake at night.

He grew more and more troubled. Finally, at the tail end of World War II, Aino and Sibelius brought a stack of manuscripts to the dining room table, and Sibelius began to burn them. The destruction made Aino sick, but she didn’t stop her husband. (She surely realized she had no power to.) It is assumed that any existing manuscript of the Eighth Symphony was destroyed in the fire.

Sending up his old works in flame was deeply cathartic for Sibelius. Aino later recalled, “After this, my husband appeared calmer, and his attitude was more optimistic. It was a happy time.”

The Symphony That Refused to Die

But the idea still wasn’t completely dead. Sibelius made brief, vague references to an eighth symphony for years afterward.

Realistically speaking, though, his inspiration had run dry: not only when it came to symphonic music, but when it came to music, period.

After 1926, he only wrote a handful of works.

It’s unclear how much he wrote during the last decades of his life that was destroyed or even conceived of but never written down.

Sibelius died in 1957. He was a few months away from his 92nd birthday.

Legacy of the Eighth – And Could It Be Resurrected?

Aino and Jean Sibelius

In the years since, scholars have looked at the remaining fragments and tried to reassemble at least a portion of the eighth to decidedly mixed results.

A few brief tantalizing excerpts have been recorded.

3 Sketches From Sibelius “Lost” 8th Symphony- World Premiere

Current views on the Eighth Symphony range from the opinion that there is enough surviving material to reconstruct the entire work – to the opinion that there very much is not – to the belief that doing so, even if it was possible, would be disrespecting Sibelius’s memory and wishes.

Maybe in the end, it’s enough to know that Jean Sibelius created a stunning oeuvre that audiences still enjoy today, even without the Eighth Symphony. Absent any major scholarly breakthroughs, it looks like we’ll have to make our peace with Sibelius’s decision to destroy his last, possibly best work.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter