By the time Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) had penned his final opera at the tender age of 37, he had become one of the wealthiest and most influential musicians in Europe. Coming from very humble beginnings indeed, he composed up to four operas per year and by the time of his early retirement he had 39 works for the stage to his credit.

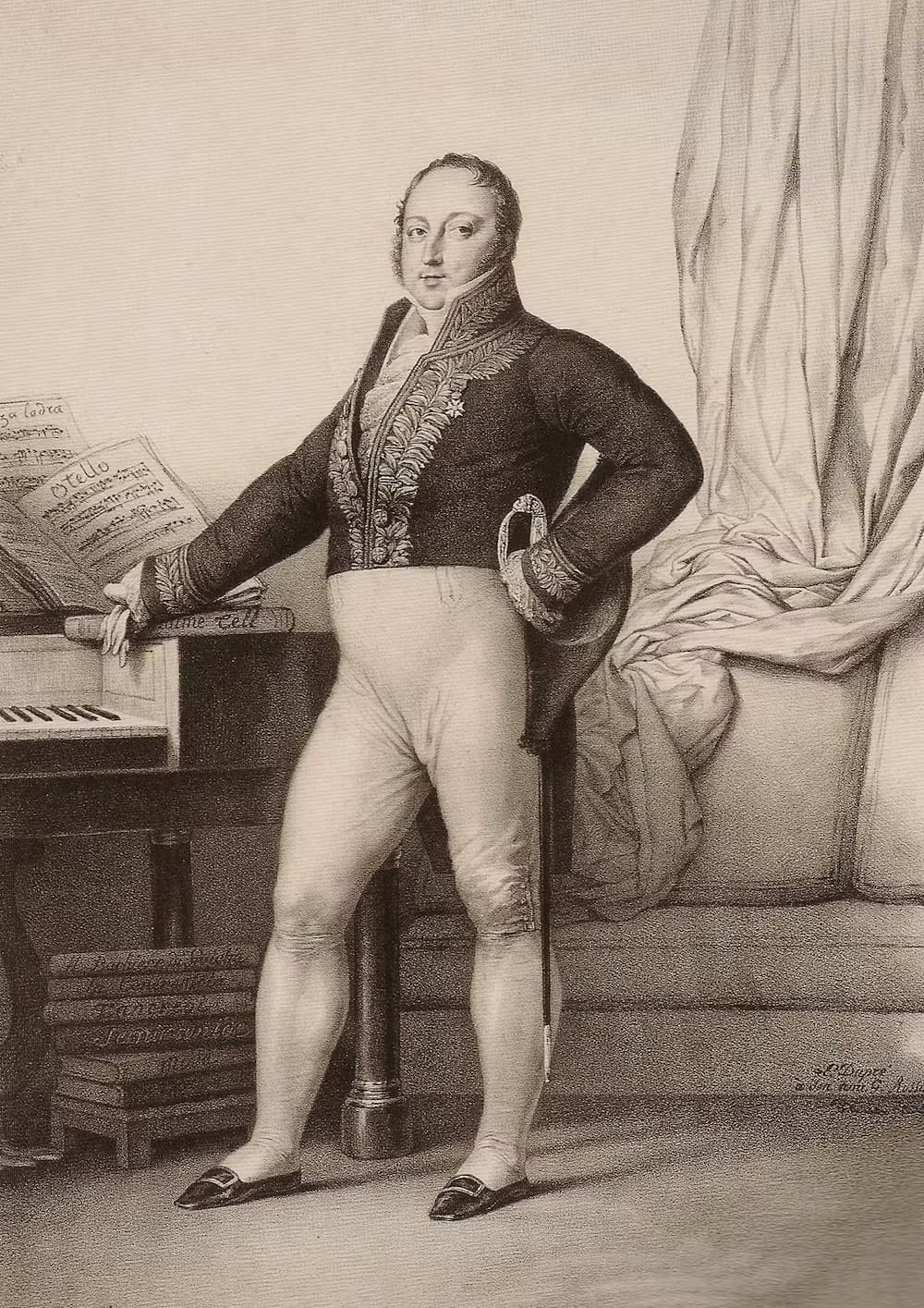

Gioachino Rossini in 1829 © Wikipedia

There has been much discussion as to why Rossini retired as early as he did, and the current thinking suggests that ill health might have been a major factor. He had contracted gonorrhea in earlier years, and he suffered from bouts of debilitating depression. It has even been suggested that Rossini suffered from bipolar disorder. Be that as it may, Rossini fortunately had no financial worries. Throughout his working life he subscribed to a brutal work ethic and he apparently also had great charisma that allowed him to cultivate a good number of wealthy friends. As early as 1804, Rossini met the wealthy businessman Agostino Triossi; he remained in contact with his “friend and patron” for many years and he composed for him a number of small works.

Gioachino Rossini: Sinfonia “al Conventello”

Giaochino Rossini, ca. 1850

Gioachino Rossini: Sinfonia “al Conventello” (Haydn Orchestra, Bolzano and Trento; Alun Francis, cond.)

Initially, Rossini made his living from operatic commissions, like the ones he received for the Teatro S Moisè of Venice. When a German composer withdrew last minute from composing the score to a one-act Farce, Rossini was approached instead. And Rossini immediately took advantage of this unexpected opportunity. He writes, “That theatre made possible a simple début for young composers… The expenses of the impresario were minimal since, except for a good company of singers (without chorus), they were limited to the expenses for a single set for each farsa, a modest staging, and a few days of rehearsals… Everything tended to facilitate the début of a novice composer.”

And we know that five of Rossini’s first nine operas were written for the S Moisè. Of course, it was not always smooth sailing, as his 1811 commission at Bologna was closed after three performances. It had nothing to do with Rossini’s music but all with the libretto, “in which the heroine’s poor lover convinces the rich imbecile preferred by her father that the girl is really a eunuch disguised as a woman.” Undeterred, Rossini set to work on his first truly successful farsa L’inganno felice, which remained popular throughout Italy during the next decade.

Gioachino Rossini: L’inganno felice

Domenico Barbaja (Barbaia) in Naples in the 1820s © Collection Museo Teatrale alla Scala

Gioachino Rossini: L’inganno felice, “Finale” (Natale de Carolis, baritone; Amelia Felle, soprano; Fabio Previato, bass; Danilo Serraiocco, bass; Iorio Zennaro, tenor; Ursula Dütschler, harpsichord; English Chamber Orchestra; Marcello Viotti, cond.)

During this time of limited or non-existing copyright laws, Rossini had to quickly compose one new work after another. As such he traveled between Italian cities conducting, accompanying and performing his latest operas in order to survive. However, he soon realized that this path wasn’t going to secure his financial future. The turning point in his professional and financial fortunes came in 1815, when he was approached by the powerful impresario of the Neapolitan theatres, Domenico Barbaia.

At the age of 22, and for the next 7 years, Rossini served as the musical and artistic director at the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. For one, he revolutionized Italian opera, and he was closely tied professionally and personally to Barbaia. Both men enjoyed the intimate company of the soprano Isabella Colbran, and Rossini’s wealth grew steadily as he formed a company with Barbaia running the highly profitable gambling tables in the foyer of the Teatro S Carlo. When Barbaia assumed directorship of the Kärntnertortheater in Vienna, he brought his star composer along and six operas were given to extraordinary artistic and financial success. Rossini became an international hero in the city of Beethoven and Schubert.

Gioachino Rossini: Maometto secondo

1817 portrait of Isabella Colbran in Saffo by Johann Heinrich Schmidt © Wikipedia

Gioachino Rossini: Maometto secondo (June Anderson, soprano; Margarita Zimmermann, mezzo-soprano; Ernesto Palacio, tenor; Samuel Ramey, bass; Laurence Dale, tenor; Ambrosian Opera Chorus; Philharmonia Orchestra; Claudio Scimone, cond.)

By this time Rossini had become an international brand and he was able to negotiate the terms of his creativity. While conducting and supervising performances of his operas in England, Rossini demanded a daily fee of 50 guineas, roughly £4,000 in today’s money. A critic sarcastically suggested that such lavish remuneration was justified “by the risk he encountered, and the inconvenience he endured, in crossing the abominable Straits of Dover.”

It has also been reported that he charged roughly £3,000 for a single singing lesson. And on 4 May 1829, Rossini negotiated a contract with the government of Charles X in France, in which he was assured a lifetime annuity, independent of his activities. During negotiations Rossini threatened to withdraw his opera Guillaume Tell before its performance at the Salle Le Peletier in Paris unless the annuity was guaranteed. The gamble paid off, as Charles X himself signed the contract. In a recent ranking of the 10 wealthiest classical composers of all times, Rossini sits comfortably in fourth position, right behind Gershwin, Johann Strauss II and his compatriot Verdi.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter